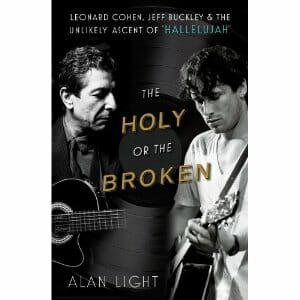

The Holy Or The Broken traces the history of a single song—“Hallelujah,” written by Leonard Cohen and originally recorded in 1984, with a chorus that invokes the Messiah and the holiday season and verses about struggles with more worldly desires.

These days, this song can be classified as inescapable, but over most of its lifetime, and through several iterations by famous musicians, it enjoyed surprisingly little favor.

Author Alan Light—who co-wrote Greg Allman’s biography, penned a book on the Beastie Boys and worked as editor-in-chief at Vibe and Spin—follows “Hallelujah” as its lyrics and instrumentation change. He shows how a relatively unknown song can be adopted, enhanced and canonized by the machinery of culture.

Leonard Cohen’s first three albums, released between 1967 and 1971, built on gently picked guitars, string sections and Cohen’s flat, low voice. His lyrics often earned comparison to Bob Dylan’s (Cohen published novels and poetry before moving into music).

When Cohen entered the studio to put together Various Positions in 1984, he hadn’t put out an album since 1979. He brought the results of his recording sessions—“Hallelujah” included—to his label, Columbia, but the label declined to issue an album. So Various Positions came out first overseas.

Initial reviews of the album after release in the U.S. on a smaller label did not mention “Hallelujah.” The original recording of the song has quintessentially ‘80s-sounding drums and a strange echo treatment applied to Cohen’s voice. Cohen claims that during recording, producers tried “… to get it to be a community choir sound, very humble.” He also notes that he wanted to “transcend the dualistic system and reconcile and embrace the wholeness”—hardly a humble goal.

Production efforts settled on a heavy swathe of backing vocals that assist Cohen on the chorus, occasional bursts of powerful electric guitar and the sturdy ballad structure often used in heart-wrenching soul songs. The combination makes “Hallelujah” into a grand, if slightly cheesy, affair.

Cohen purportedly worked on the song’s lyrics for years, whittling them down to four verses from a pool of 80 he had written. (Cohen said of songwriting, “It’s not the siege of Stalingrad. . . but these are tough nuts to crack.”) For those uninitiated in the ways of “Hallelujah,” the chorus of the track consists entirely of repetitions of its title. The verses contain religious references—“I’ve heard there was a secret chord/ That David played, and it pleased the Lord,” though Cohen intended “to indicate that Hallelujah can come out of things that have nothing to do with religion.” Things like watching a woman “bathing on the roof,” before “she tied you to a kitchen chair.”

As soon as Cohen started performing the song live, he changed the lyrics, making it “much darker and more sexual.” Highlights of the new verses include: “but love is not a victory march/ it’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah;” “I remember when I moved in you/ and the holy dove was moving too;” and “Now maybe there’s a God above/ but all I ever learned from love/ is how to shoot at someone who outdrew you.”

In 1991, a Cohen tribute album came together, with artists like R.E.M., Nick Cave and John Cale recording their own renditions of Cohen’s tunes. Cale, with impeccable avant-garde credentials as one of the original members of the Velvet Underground (he also has respected solo albums and an impressive record of production work for the likes of the Stooges, Nico and Patti Smith), chose to record “Hallelujah.” His version took place alone at a piano. It’s a “Hallelujah” on the verge of alienation and despair, if not there already—in Light’s words, Cale’s version comes off “purged of joy.” Cale also changed the verses, taking two of Cohen’s recorded originals, and then adding three of the darker ones from live performances.

The next shot at “Hallelujah” came from Jeff Buckley, the son of ‘60s folk and pop singer Tim Buckley. Young Buckley signed a contract—also with Cohen’s Columbia records—in 1992, after playing all over bars in New York and getting accolades from the likes of Allen Ginsberg. (The famous poet hooted at Buckley in appreciation during a show, but Buckley didn’t understand his intent and told him “you don’t have to be a dick.”)

Buckley spent a while recording his debut, Grace. It contained a solo, guitar-driven cover of “Hallelujah,” a pastiche from “more than twenty takes.” Buckley used Cale’s lyrics. Grace came out in 1994, but it failed to crack the top 100 in the U.S. Meanwhile, Cohen had given up music for life in a monastery.

Normally, it’s three strikes and you’re out—but not this time. Buckley drowned in 1997, and as is depressingly often the case, his work attracted more interest in the wake of his death. Then Cale’s version of the song appeared in Julian Schnabel’s movie Basquiat, and again in the massive popular movie Shrek (though Rufus Wainwright recorded the version for the soundtrack).

The real turning point occurred after Sept. 11, 2001, when VH1 picked Buckley’s “Hallelujah” to play in the background during a memorial video that ran every hour on the cable network. Most of the people involved acknowledged that the song’s content “‘doesn’t quite fit what was happening’”—after all, Buckley once said that the song “is not an homage to a worshipped person. . . but the hallelujah of the orgasm.” But as a producer at VH1 put it, “create an emotion, people react to it, they rarely hear the whole thing.” Or, as the singer Jon Bon Jovi says of those singing (and listening to) the song: “I won’t name the artists who have no clue of what’s inside those words, but I’ve often said that people in America know the chorus to that song, people in the rest of the world know the verses.”

The song’s significance started to change. As described by the writer Michael Barthel, this process “erased the line-by-line, verse-by-verse meaning and replaced it with an overall feeling of sadness.” With the lyrics ignored, the feeling behind the tune became a juggernaut. (The book contains almost too many testimonials reiterating this fact.)

Shrek was ahead of its time—the song popped up in shows like ER, Scrubs, The West Wing, The O.C., House, The L Word and Without A Trace, often during climactic finales involving death, aligning with the tragic 9/11 tribute video. The song also became traditional fare for shows like American Idol and The X-Factor. The CEO of Sony music publishing now says “‘Hallelujah’ is a brand.”

Perhaps the most remarkable “Hallelujah” story occurred in England in 2008, when an X-Factor singer sang the song on the show, sending her version to the top of the charts in the week before Christmas. A dedicated Jeff Buckley faction worked to get his version to the No. 2 spot in the same week, so two different versions of the song held the top two spots on the charts. Because of all the interest in the tune, even Cohen’s old version cracked the top 40.

The story of “Hallelujah” tells a story of the massive power of cultural machinery. When that machinery gets its teeth into a piece of art, it can alter and popularize, transforming the relatively unknown into a modern standard … for commercial purposes.

According to Light, “Hallelujah” is “perhaps the only song that has truly earned that designation [modern standard] in the past few decades.”

Just one person needs to use a song to successfully connect with an audience—in a way that doesn’t have to relate to the song at all—to establish a commercial franchise. With movies, TV shows, advertisements and musical shows like American Idol, a lot of people keep on the lookout for songs that create an emotion. But we also see a lot of randomness and a lot of luck, sometimes based on little more than the record collections of powerful people.

Leonard Cohen eventually left his monastery, only to find that all his money had been embezzled by a former employee. He started releasing music and going on tour again—he needed to make a living.

While Cohen had plenty of listeners before “Hallelujah,” the wild success of the song surely increased his fan base (though some might argue the opposite has occurred, as people think, “Good God, I can’t stand another rendition of that song!”).

Cohen’s manager originally said “it wasn’t worth bothering to execute their contract” for Various Positions, since Columbia refused to release it. So Cohen has not seen a cent for all the various takes on “Hallelujah.” But when he needed money from music, “Hallelujah” came through.

Imagine—at times, the enterprise of cultural reproduction is even profitable for the artist. Hallelujah.

Elias Leight is getting a Ph.D. at Princeton in politics. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and writes about music at signothetimesblog.