Rhys Darby: It’s Just An Act

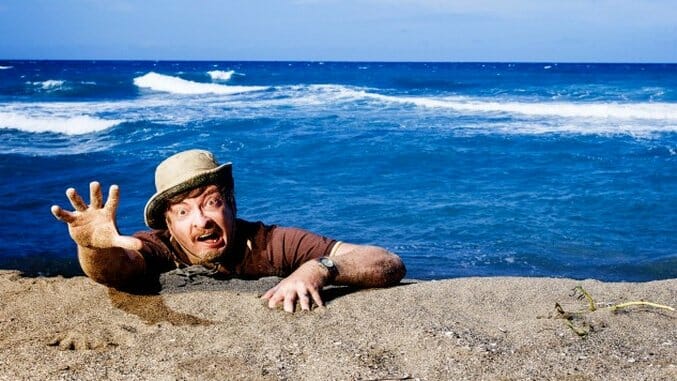

Mobile Lead Photo by Kate Little Photography Comedy Features Rhys Darby

New Zealand, an island nation known chiefly as the world’s second largest exporter of wool, is also its largest exporter of Rhys Darby, perhaps Hollywood’s only actor slash writer slash stand-up slash globetrotting monster hunter. And if he’s not the only one, he’s certainly the busiest. In the last year alone, Darby delivered memorable performances in the bumpy new season of The X-Files, TBS’s Lost parody Wrecked, and Hunt For The Wilderpeople, the gorgeous indie drama from Flight of the Conchords and Thor: Ragnarok director Taika Waititi, another New Zealander. He also filmed appearances in Australia’s Whose Line Is It Anyway? reboot and Netflix’s upcoming A Series of Unfortunate Events. Darby’s specialty is the outcast, the oddball, the lovable sad sack, the well-intentioned if ultimately misbegotten chump—wide-eyed, stiff-shouldered, laser-focused on all the wrong details. He earned initial acclaim as the hapless manager Murray Hewitt in Flight of the Conchords—which, fight me, remains one of the funniest buddy comedies of the last decade—but he developed his performance style as a stand-up in the late ‘90s, in a New Zealand comedy scene that largely grew up with him.

“In the early days, there wasn’t really much of anything,” recalls Darby, who served in the New Zealand Army before studying journalism at the University of Canterbury. He took up comedy “as a hobby” with his friend Grant Lobban, forming a duo they dubbed Rhysently Granted. “We did surreal sketches and music,” he says. “We did it for nothing. We’d go down to bars that looked like they might take us, and offer our services for a free beverage.” Little of their early work survives—this was before YouTube—though their 1997 music video “Jandals” offers a tantalizing glimpse into the past. It’s a deliciously lo-fi, punk-y ode to flip-flops featuring Darby’s ill-synced vocals, alternatingly controlled and clownish dance moves, and the same broad facial expressions he employs as a jungle hermit in Wilderpeople.

Watching in 2016, I can’t help but think of the analog aesthetic common to so much of Tim & Eric’s work, or even web sketch by younger groups like Brooklyn’s Meat. It strives for silliness over sense, shifting (mostly) fluidly between faithful genre parody and straight-up tomfoolery. This was true of their live shows as well, if a 1997 performance of “Mrs. Whippy” is any indicator. The song, parodying soft serve franchise Mr. Whippy, opens with Darby singing the melody of “Greensleeves” before Lobban dives into a thumping bass line. It’s a bizarre incongruity in a number full of bizarre incongruities, from Darby’s dialogue portions to Lobban’s childish wave at the song’s end. But like all good comedians, of course, they are fully committed and wholly unapologetic, making “Mr. Whippy” a fascinating and rare look—given its period—at a comic aesthetic in its infancy.

Darby cultivated the Christchurch comedy scene in pretty much the same way younger alternative comedians are building their own communities in the backrooms of New York, Los Angeles and elsewhere—by self-producing shows and open mics alike. “We had a comedy night at a bar called the Green Room, which was sort of a performance café,” he says. “We had a comedy night on Saturdays, and once a week, on Wednesdays, there would be an open mic, looking for talent. But it was few and far between—not in terms of talent, just in anyone who’s even interested in doing it.”

This was still the late ‘90s, when it was challenging to get the word out to prospective performers in a relative comedy vacuum. Darby recalls that his first stand-up performance, in 1997, came courtesy of a newspaper ad for the open mic portion of a booked show. “There was a number you had to phone, and you put your name down,” he says. “I thought, oh, I could be a part of this.” He earned a three-minute spot in a show featuring headliner Mike King, who Darby describes as “one of the two New Zealand stand-ups who were actually working”—a far cry from the uzzing contemporary scene.

From the beginning, Darby embraced not just the absurd but the dangerously absurd. “I was very nervous,” he says of that first mic. “I had a routine of sorts—it was about fishing. I remember right from the start doing a physical movement, casting a fishing line into the sea, and I just told people, you know, the most exciting part about fishing is the casting. Then I stood there for, I think, possibly a minute-thirty of the three minutes, waiting for the fish to be caught. It was laughter through pain—it was anti-comedy. And that sort of started me off as someone who was definitely going down that weird route, who was not going to do the general setup-punchline type of humor. That was how it all started for me.”

This description reminded me of one of my favorite of Darby’s routines, “Robot Man”. It’s so stupidly simple: he does a robot impression, then explains, in depth, how he did it. “How many people thought I was a robot there? I’m not. It was just an act—basically what I’m doing is I’m moving like a robot.” The joke evokes Ian McKellen’s famous “Acting” monologue in Extras, but I think the combination of Darby’s physicality and his cheery deadpan—and, sure, his accent—makes “Robot Man” a much more satisfying experience. (It probably helps that in stand-up there’s no room for a straight man, like Ricky Gervais in that Extras scene, to acknowledge the joke.) It’s the exact sort of circuitous storytelling, peppered with idiosyncratic detail—he goes so far as to explain how a microphone transmits sound to speakers—that makes Flight of the Conchords so eminently re-watchable.

It wasn’t long before Darby moved to Auckland, already home to an honest-to-goodness-comedy club, and started headlining shows with a small coterie of his peers. “There were probably about ten of us that were starting to get names for ourselves, but certainly no more than that,” he says. “At the height of my time in New Zealand, those stand-up years, I was probably doing three gigs a week at most.” This might sound shocking to anyone familiar with the grind required of stand-up comics in New York or LA, which often entails three or more shows a night. But Auckland was a small pond. “By the time I got to the third gig, some of the audience members would say Hey, I saw you on Tuesday!” he recalls. “It was the same crowd, and I hit the ceiling quite quickly. By 2000, I thought it was time to leave and head to the UK.”

That was where Darby eventually met the Flight of the Conchords, at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, later collaborating with them on the BBC radio series that preceded the HBO series. (He came up with the running “band meeting” gag on the spot when they started recording.) His TV and film career took off from there, and today he identifies as an actor before a comic. “Stand-up was always a means to an end,” he says. “I don’t want to be seen as the voice of a country, I don’t do political jokes. I’d rather be part of a world.” He rigorously applies this ethos to his stand-up, when he has the time to craft material from thoughts jotted in his always-present notebook—whether for an hour of stand-up or his monthly showcase, “Rhys Darby’s Saying Funny Things Society,” at LA’s Largo Theatre.

“I like having a narrative that runs through it,” he says, noting that these are often science fiction-based—he is, after all, devoted to the paranormal, and co-hosts a podcast about cryptozoological creatures. “I like having a beginning, a middle, and an end, and I like doing callbacks. I’ve done my share of one-man plays. I think that’s me enjoying movies and wanting to create a movie onstage for people.”

But, he adds, it can get exhausting to play so many characters in a single show. “Now that I’m 42,” I’ve cut out a lot of that,” he says. “It’s like going to the gym for an hour.” His wife, producer Rosie Carnahan-Darby, cuts in, “I’m looking forward to the armchair comedy of your future,” and Darby agrees: “I really want to get down and eventually become Ronnie Corbett—I’m sitting in a chair, I spin around, and I tell a story you’ve probably heard before.” It’s the perfect context, perhaps, for a long-lost joke about fishing.

Seth Simons is a Brooklyn-based writer, performer, and birdwatcher. Follow him @sasimons.