Nostalgia for the New: Grant Morrison’s New X-Men Turns 15

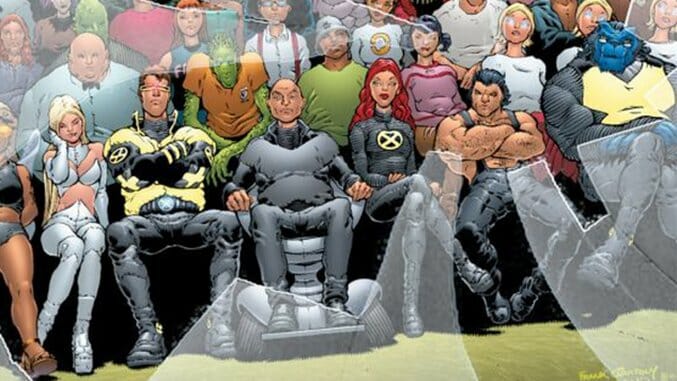

Main art by Frank Quitely Comics Features Grant Morrison

A note: while we acknowledge that no collaboratively produced comic book is the sole creation of its writer, Grant Morrison’s run on New X-Men was brought to life by ten different pencillers across its 41 issues. For the sake of simplicity, this article will primarily credit Morrison for guiding the book, and will discuss the contributions of its individual artists as appropriate.

Also, spoilers below for a 15-year-old comic.

Few would attempt to argue that the X-Men family of books—for many years, the most sprawling and best-selling corner of the Marvel universe—is in a great place today. Putting aside longstanding rumors of internal grudges from Marvel and parent company Disney against the property due to Fox’s possession of mutant-related film rights, the X-subsection of Marvel’s publishing line has shrunk to only five books—two of which are Wolverine solo vehicles. Later this year, X-fans will face the mixed prospect of two X-related events, one ominously entitled Death of X and the next pitting mutants against the Inhumans, a fully Marvel-owned property that has seen a substantial push in recent years. With the Inhumans-spawned Terrigen Mist cloud proving both toxic and sterilizing to most mutants, the upcoming Inhumans vs. X-Men event seems like an in-narrative iteration of a conflict playing out behind the scenes of Marvel Comics.

If 2016 is shaping up to be a tumultuous and potentially depressing year to be a mutant-lover, it at least offers a convenient reason to look back at the property’s last truly groundbreaking zenith. Published 15 years ago this summer, New X-Men #114 by writer Grant Morrison and artist Frank Quitely kicked off a bold new era for the then-stagnant franchise. In a time before annual relaunches, Morrison and Quitely’s swift takeover reads like emergency life-saving surgery, swapping out gaudy over-pouched spandex for latex and kevlar with neon-yellow trim. The Scottish scribe also cauterized the cast down to a core crew: Cyclops, Jean Grey, Wolverine, Beast, Professor Xavier and the surprise addition of a scantily clad Emma Frost. The group announces their presence on Quitely’s first cover like a rock super-group on their way to a fetish party, backlit by a blazing psychedelic sun.

New X-Men #114 Cover Art by Frank Quitely

Revisiting the series a decade and a half after its debut, it’s surprising how little revisionism Morrison indulges in. Yes, the book keeps to itself—Storm appears in one issue dressed in her X-Treme X-Men garb from the concurrent comic written by Bronze Age mutant architect Chris Claremont, but no mention is ever made of the abysmal Chuck Austen-scripted Uncanny X-Men series from the same period—yet it’s infused with X-history. Cyclops bemoans his then-recent possession at the hands of Apocalypse, Emma’s disastrous first attempt at teaching weighs heavily on her diamond-clad mind, Beast remains anxious over his increasingly furry inhumanity and Jean and Logan stay forever star-crossed. But for a book that begins with the long-lost evil twin trope, New X-Men’s bold new era is built firmly on its existing foundation. While Peter Milligan and Mike Allred’s X-Force/X-Statix, the other visionary X-run from the early part of the century, torched its roots, started from scratch and self-immolated when its creators were finished, New X-Men exists within the framework of its storied legacy and inspired much of what’s come since.

Morrison’s twofold direction—the return of the school setting and a move toward global paramilitary mutant first-responders—reverberates through nearly every X-Men run since his departure from the book in 2004. Both Kieron Gillen’s Cyclops-Magneto-Namor alliance and Jason Aaron’s Headmaster Wolverine romp owe much to Morrison’s groundwork, and Joss Whedon and John Cassaday’s cinematic 25-issue Astonishing X-Men simply wouldn’t exist without the New X-Men era of a tight team dynamic highlighted by a persistently pithy Emma Frost.

This isn’t to say that Marvel quite knew what to do with every Morrison idea. Magneto’s masquerade as Xorn, a Chinese mutant with a star for a head, requires some suspension of disbelief, even when re-reading the series with full knowledge of the twist to come. His drug-assisted collapse as both a mutant leader and as a symbolic icon remains a biting deconstruction of his cult of personality, even if his human concentration camps feel extreme in the face of his childhood in Nazi Germany. Morrison and artist Phil Jimenez, who drew several memorable arcs on the book, give Magneto a tragically fitting send-off at the claws of a grief-stricken Wolverine, only to have New X-Men’s most important long-running plot undone and needlessly complicated mere months later by Marvel editorial with the reveal that Xorn really was Xorn all along, and that the real Magneto—actually, it’s better if you just pretend anything Xorn-related post-Morrison was wiped away by the Scarlet Witch in House of M. It may be the single most comforting “headcanon” of all time. (You’re welcome.)

New X-Men #127 Cover Art by Frank Quitely

Aside from the modern-day conception of Emma Frost as a diamond-skinned one-liner factory and the pink-haired enfant terrible Quentin Quire (effectively rescued and rejuvenated by Jason Aaron in his Wolverine and the X-Men run), Morrison’s most prominent addition to the cast is Fantomex, the faux-French Weapon Plus survivor with an external nervous system in the form of an occasionally sexy UFO. A shameless nod toward European pulp characters like Diabolik, Fantomex helps Morrison reveal his second major retcon from his time on the book (following the existence of Cassandra Nova): that Wolverine’s Weapon X designation is actually a Roman numeral, and that the program didn’t stop at ten. After a few post-Morrison years in obscurity, Fantomex has become a staple of the black-ops X-Force lineage of books, most recently transferred under the Uncanny X-Men banner.

Fantomex’ stylish and hyper-violent introduction at the hands of artist Igor Kordey is also emblematic of Morrison’s run on the book as a whole. Despite working with artists from across the globe, from Filipino superstar Leinil Francis Yu to Utah-born DC stalwart Ethan Van Sciver, New X-Men carries a distinctly European vibe, more “high-concept science-fiction with a social message” than “superhero punch-fest.”

(As an aside, Kordey was supposedly asked to draw some of his issues in as few as two weeks as primary artist Frank Quitely fell behind. Despite criticism at the time, Kordey’s distinctly gnarled work remains readable and dynamic. As stupefying as it is to imagine all 41 issues drawn by Quitely, only Keron Grant’s bare-bones sole issue stands out as ill-fitting Morrison’s take on the property.)

Lest nostalgia deify New X-Men a little too much, it’s worth pointing out that Morrison’s impassioned revival shares a shortcoming with most X-Men runs: it leans heavily on a metaphor about oppressed people without featuring the actual oppressed community. For years, this meant the often lily-white X-Men team symbolically countered racism, but under Morrison’s pen, the central X-metaphor shifts from one of racial inequality to one of sexuality politics. From the implications of Quitely’s bondage-y costume redesign to Van Sciver’s infamous Easter egg of hiding the word “sex” on every page of issue #118 to Beast’s ill-conceived faux-coming out (“I’m as gay as the next mutant! I make a great role model for alienated young men and women. Why not?”), Morrison suffuses the book with sex, sexual tension and sexuality.

New X-Men #139 Interior Art by Phil Jimenez

And just as heterosexual America consumes the pop-culture contributions of queer artists, from Ellen to the black trans women coining tomorrow’s trendy catchphrases, without granting legal rights and protections to LGBTQ+ folk, so too do Morrison’s U-Men harvest mutants for powers without deigning to view mutants as fellow humans worthy of life. Yet Morrison never goes so far as to introduce an actual queer character, or follow through with Beast’s attention-seeking fake coming-out. Morrison’s queering of the mutant metaphor throughout New X-Men is a welcome addition to the X-Men legacy, but the absence of actual queer characters tarnishes this particular contribution.

In all fairness to the creators currently stewarding the X-Men line, the books continue to sell well, and the announcement of next year’s unfortunately titled RessurXion means the franchise isn’t quite on the last legs some voices on the internet would have you believe. Still, looking back at the 15 years that have passed since Morrison and Quitely obliterated Genosha while bringing the brand itself back from the brink of extinction, it’s hard not to feel nostalgic for the “new” in New X-Men, an adjective that seemed—at least for a few brief years—to indicate something tangible about the story contained within its covers.

Steve Foxe is the assistant editor of Paste Comics, has a secret day job in children’s publishing and writes comics and licensed books in the wee small hours of the morning. He lives in Queens and tweets about horror movies, cats and gay stuff at @steve_foxe