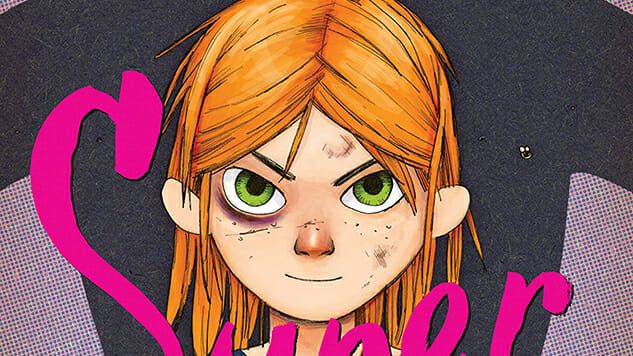

Jim Rugg on the Decades-Spanning Legacy Behind His Homeless Ninja Badass, Street Angel

Jesse Sanchez Returns in the Cape-Skewering Super Hero for a Day

Comics Features Jim Rugg

Street Angel is a quirky, genre-spanning comic that hides decades in its pages. Jim Rugg may have begun the project 14 years ago, but the Pennsylvania-based cartoonist uses the medium’s lifespan to flavor the story of a badass, spunky ninja adolescent scrounging for a place to sleep in the inner-city hell of Wilksboro. Rugg and co-writer Brian Maruca have used that foundation to dive deep into the culture of Depression-era comics à la Little Orphan Annie, to the extreme action onslaught of the ‘90s. It’s an irreverent, post-modern medley that works in absurd harmony, rooted in the deadpan disposition of its titular character, née Jesse Sanchez, as she fights off the dregs of humanity while searching for a hot meal.

Paste brought you a preview of Rugg and Maruca’s last Street Angel graphic novel, The Street Angel Gang, and the pair returns this Wednesday with Street Angel: Super Hero For a Day. The one-shot invites another genre into its folds, with a biting take on the capes crowd. In the book, Sanchez’ friend Emma discovers a fallen alien with a dazzling, flight-granting ring—a scenario that should sound familiar to any Green Lantern fans. Though Sanchez would rather pawn it for some food, Emma tries it on, leading to a brutal takedown of a creepy Superman analogue named Captain Alpha who embraces every connotation of his adapted surname.

Paste exchanged emails with Rugg to discuss his creation, his process and if he has beef with the super-folk.![]()

Paste: Let’s start at the beginning. Tell me about the creation of Jesse Sanchez and her debut in 2003.

Jim Rugg: I was making mini-comics at the time and was bored with the new comics that I saw at my local shop. I decided to make a comic that I wanted to see there—something different than all the other comics. Street Angel grew out of that. We combined superhero comics and alternative comics and came up with the Deadliest Girl Alive, half ninja master on a skateboard, half homeless, hungry, lonely kid.

Comic books culture was still a boys’ club back then and I wanted to make a new hero, someone that could out-fight all the tired, old superheroes and didn’t look like more of the same boring thing. As we wrote stories and designed her character, Jesse Sanchez became the fun, action-hero Street Angel.

Street Angel: Super Hero for a Day Interior Art by Jim Rugg

Paste: I read that you grew up in the country and have never lived in the city. What led you to develop the inner-city cesspool of Wilksboro? How much did your love of exploitation cinema inform it?

Rugg: Exploitation cinema is an influence for sure. But cities always had a lot of energy around them. The people in my rural community had a mistrust of the city and “city slickers” so there was a forbidden mystique around the “big city.” Then when I started reading comics, cities were the home of super heroes! And that made them magical to me—a far-off land full of wonder and wonderful characters.

Superhero comics are so connected to cities, both in story but also in terms of the comics industry. In the ‘80s, comics were all about the anti-hero cleaning up their city (at least my favorite comics were). Part of Street Angel is that she’s a homeless kid in a dangerous world, so that was the starting point for Wilksboro.

Paste: I see Street Angel as this decades-spanning buffet of different comic eras. On the more obscure end, you’re playing with Great Depression-era scamps like Orphan Annie and then that’s filtered through extreme action, ‘90s ninja adulation. This one-shot bridges that time gap with classic superheroes, mainly a Green Lantern origin story spoof. What inspired you to tackle this era and genre?

Rugg: That’s a great description of Street Angel. I love all kinds of comics—old newspaper strips, ‘90s extreme,’ 80s black-and-white, alternative, webcomics, manga, European albums…

Superheroes were my gateway. I think of Street Angel as a superhero comic, even though most of her adventures don’t look like typical superhero comics. As this story came together, it seemed like the perfect idea where we could lean into the classic superhero comics that made me want to be a comic book artist.

When we write stories, we start from different places—sometimes we have a scene or concept or character that we like and we build from that. Each story is a chance to design Jesse’s world and cast and setting, including details like color palette and style. As we got into Super Hero for a Day, it became obvious that we could include some classic superhero motifs and that would be a great way to show what makes Street Angel different and unique. I love the idea of her next to a classic superhero type. Plus Bell loves superheroes and comics, so it was a chance to see her excited and happy! Bell is fun.

Street Angel: Super Hero for a Day Interior Art by Jim Rugg

Paste: What are your favorite comics from the eras that inform Street Angel>/i>?

Rugg: You nailed a couple of them. Annie and Dick Tracy are adventure comic strips that I like from the ‘30s/’40s era. Early comics that I admire include Little Nemo for its inventive use of the comics environment and page. Krazy Kat is great for the joyful exploration of cartooning, language, and repeating/exploring the same simple concept thoroughly. Peanuts: kids, minimalism, character. EC Comics were important for me because of their high level of craft and short stories and so many great artists.

I like some of the dumb sci-fi/monster comics of pre-Marvel Universe. Silver Age stuff is great for the bizarre superheroes and Marvel Universe and Kirby and Ditko. My first real Kirby comics were from the ‘70s. When I started reading comics, that era of Kirby was underappreciated. So I could find a lot of that stuff cheap, like OMAC, Devil Dinosaur, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kamandi. It was great for the inventive ideas, energy and world building. The weirdness of ‘70s Marvel produced a few gems, highlights for me are Gulacy’s Masters of Kung Fu and Jungle Action featuring Black Panther. ‘80s comics were dominated by Frank Miller (Ronin, Daredevil, Batman, Elektra) and Alan Moore for me.

Then I went through a deep-dive period into the ‘80s black-and-white explosion that followed the Ninja Turtles. That material has had a huge influence on me because it was a bunch of people self-publishing and doing everything themselves which is exactly what I do. And talk about weird—I love that comics can be so eccentric and strange because they can be the work of one person and they are inexpensive to produce, so you can make comics that look like anything. ‘90s—McFarlane, Liefeld, Platt, Image, Bisley…they traded clear storytelling for dynamic graphic enthusiasm and I loved it! Alternative comics like Clowes and Doucet. They made worlds that I was both afraid of and couldn’t get enough of. The Hernandez Bros. approach to world building and character has been huge. Chester Brown’s Yummy Fur changed my life.

In the 2000s, I started to read manga like Akira, Mai, Tekkon Kinkreet, Fist of the North Star, Tezuka. I also started reading a lot of mini-comics like Fort Thunder and King-Cat. The design of Highwater Books had a huge influence on me. Kramers Ergot expanded what comics were for me. I also got into Deadline magazine, especially Jamie Hewlett (Tank Girl and Fireball) and Shaky Kane. Lately I’ve started looking at more picture books. So, yeah, lots of influences and favorites.

Street Angel: Super Hero for a Day Interior Art by Jim Rugg

Paste: Jesse offers some brutal superhero take-downs, contrasting the romanticism of the genre with the abject reality she witnesses. (“Superheroes dress like assholes to stand out above everyone else.”) Do you share that vitriol, especially as capes have flooded popular culture through every medium?

Rugg: Yes and no. I enjoy a lot of superhero comics and of course, there are a lot that I think are terrible. (I enjoy some of those too.) My complaints are probably a lot different than Jesse’s. For example, I like superhero fashion. My vitriol would be aimed at bad storytelling and corporate practices that disgust me.

Paste: I could tell you had a design background just from the cover of Superhero For a Day—four separate fonts on Ben-Day Dots. It’s the same post-modern approach you apply to your narrative, but graphically. Can you talk about your approach to fonts and lettering (and the vibrant colors of the letters) throughout the book?

Rugg: My approach to fonts/lettering is that they are a graphic element of the reading experience. Legibility is a concern, but after that, it becomes how can the font/lettering add to the story. In the case of the cover, I wanted to punch-up the word HERO! The story is a playful deconstruction of the superhero genre. So let’s break apart the word “Superhero” on the cover itself.

Within the story, I use a lot of hand lettering for dialogue and incidental lettering (like on signs and the title page). Because I’m doing all of the visuals (drawing, color, letters), I try to make the lettering, drawing and story fit together. We use different parts of our brains to understand images and read text. I have seen a lot of comics where the art and lettering seem alien to one another. So I use the same tools to create both with the intent that they complement one another and they look like they are part of a whole.

With this story, the theme is superheroes and a common element is secret identities. Street Angel is a badass superhero and Jesse Sanchez is a homeless, hungry, scared kid. Superhero comics and hand-written, magic marker on cardboard signs provided references for the lettering in this story. The coloring on the cover lettering is a reference to the traditional CMYK process that has been seen in superhero comics forever.

Street Angel: Super Hero for a Day Interior Art by Jim Rugg

Paste: Conversely, I’m used to designers taking an overly clean, antiseptic approach to illustration, but you embrace process and don’t hide the stages—so many zigs and zags of sketches behind colors. You can almost smell the graphite. It’s a celebratory and raw embrace of the medium. What’s your overall process?

Rugg: I love that description, thanks! One thing I always struggled with in the digital process is how clean/perfect color can be. So I have always tried to find ways to add texture to my art.

My process is writing a script first. I do that with Brian Maruca, my writing partner. We’ve been writing together for 15 years. So we’re like co-writers/co-editors and BFFs/arch-enemies, bickering married couple maybe? Once we wrestle a story into existence, I break it into a script so I have a plan for how many pages it will be, what’s on each page, and so on. This script is just a rough plan. The end result is always different. I think this story ended up being four pages longer than the script because things would take up more space when I drew them or we’d think of something to add or see something was unclear or missing. This happens in the drawing process, stuff just doesn’t turn out exactly how you think it will. Pretty normal. Every cartoonist I know has this experience to some degree.

Once I have a script, I print it out and staple it together like a book. I do this so I can carry it around with me and draw directly on the script. In these script books, the left page is script and the right page is blank. My first drawings are very fast and rough. I draw them directly on the script (and continue to make notes and revise the script).

I make two pages at a time, in the form of a spread. Open any book, the left and right is called a “spread.” I design for print, so each spread is like a canvas. For this book, when I had a rough idea of what the spread needed, I drew it in Photoshop using a Wacom tablet and stylus. This is the first book that I did this. Before this book, I drew the layout on paper. Then I add a new layer and revise the drawings—this is like the “penciling” stage. I print this in light blue ink on 11 × 17-inch paper and I do a finished drawing using pencils. Then I scan these drawings and color the page. Unlike a lot of colorists, I don’t flat my colors. I zoom out so that the spread is very small and I can see the whole thing on the screen and I color it very fast with a big brush. Then I keep zooming in and revising and adding details until I’m done. This kind of process probably creates the sketches and textures that you mentioned as I add layers of color and build up the finished art.

Then I save the pages for print. I place them in an InDesign file so I can easily see and read the story in progress (and share it with Brian and anyone else). I return to the Photoshop layered file and create a layout for phone screens. This usually means a tall, vertical scroll. Save that for later and boom! Next page. A spread takes about 2 ½-3 days.

Street Angel: Super Hero for a Day Interior Art by Jim Rugg

Paste: Is there ever any trepidation in appearing insensitive regarding homelessness/poverty to audiences unfamiliar with Street Angel’s legacy? What do you think that character trope brings in today’s context?

Rugg: Yes. There is trepidation. I do not want to exploit or hurt anyone, especially people who are marginalized. Poverty and wealth distribution has become a bigger media topic since the character first appeared, but that has more of an influence on Street Angel than vice versa. If that character trope brings anything in today’s context, it might be another representation of a group of people who are often ignored and another reference to the disparity of wealth distribution that we’ve seen grow over the last several decades. But to suggest this comic is political is a stretch and I think anyone looking for that will be disappointed. I view Street Angel as escapist fantasy, which is what comics were for me when I was a kid desperately searching for something different in my life. Comics saved my life. Making comics is my way of trying to repay that. Her status as a homeless child is a reaction to Bruce Wayne being a rich guy more than any statement on social/economic issues. I think it’s a unique characteristic and one that influences the character’s behavior. Financial struggles are something I think a lot of people can relate to unfortunately, but I’m not vain enough to think that my comics make a tangible difference in this area.

Street Angel: Super Hero for a Day Interior Art by Jim Rugg

Paste: The backmatter displays a thorough chronology of Street Angel, starting as a self-published miniseries on. It seems like Jesse is always in the back of your mind. What other genres/periods would you be up to skewer? Would you ever inject her into the grindhouse of Afrodisiac?

Rugg: Manga and webcomics are the genres that most interest me right now. Grindhouse is a huge influence. I internalized grindhouse for five years while working on Afrodisiac. It’s always going to be there. I think you can see bits of it here and there in everything that I do. I love ‘80s black-and-white explosion/self-published comics. I often think of doing a Street Angel comic that would be a love letter to that period and style. They are definitely connected to the grindhouse. But if I were to go in a different direction, it would probably be more of a manga or webcomics direction.