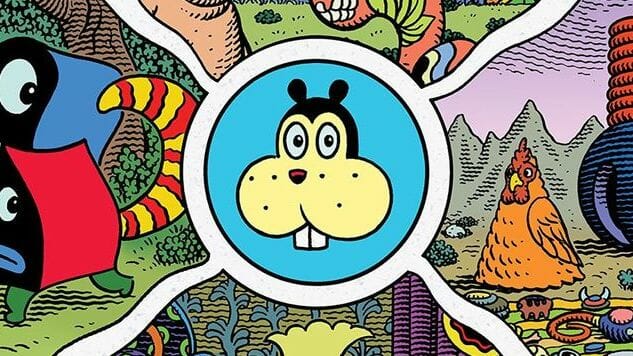

Cartoonist Jim Woodring Talks Poochytown, Hallucinations & Los Angeles in the ‘60s

Art by Jim Woodring Comics Features Jim Woodring

Jim Woodring’s visionary art (his term, as evidenced by his website, which promises “visionary art for adventurous spirits,” but an accurate one) is effortful to produce and effortless to consume. Unlike most comics that draw on psychedelic imagery, its narrative line is oddly clear, especially considering that it uses little to no verbal language. Frank—his appetite-driven, buck-toothed, cat-faced humanoid protagonist—is a sort of Candide-like figure, stumbling through a world that mostly seeks to demoralize and consume him. Bold with frills and curlicues, it manages to convey the dangers of both humanity and nature, both as crystalline and as packed with ephemera as William Hogarth’s 18th-century prints but lacking their moral instruction. The result is something timeless and broadly appealing. Poochytown, his latest creation, out now from Fantagraphics, contains a surprisingly gentle message about coming to understand our neighbors and those folks with whom we are thrown together against our will. We are all human, even those of us who are not. Woodring answered our questions over email, including some explanation of his process and those works of art that inspire him most.

![]()

Poochytown Cover Art by Jim Woodring

Paste: Talk to me about how you plan out your books (or if you do). Because they don’t really have words in them, do you write out a narrative first? Or just let it flow?

Jim Woodring: One of the reasons I’ve done so many Frank stories and drawings compared to other sorts of comics and pictures is that from the beginning they have come to me almost as if dictated. The writing process consists of going to a quiet place and writing down the ideas as they present themselves.

I know which ideas are keepers because they come with a certain invisible glow. These crypto-luminous ideas accrue without any thought on my part about what they or the resultant story represents; sometimes the meaning is obvious, sometimes hopelessly obscure—to me, anyway.

Over time, as the characters have increased in number and more territory has been revealed, I realized that the place where the stories are set—The Unifactor—was calling the shots and setting the agenda. Logically I know the Unifactor exists in me, but it doesn’t feel that way. It operates as an entity entirely separate from my conscious self.

I know that all this sounds hopelessly arch and contrived, but it’s the truth.

Paste: When do your most luminous ideas tend to come to you? Are there things you do that help facilitate them? (For example, I know you meditate. Does that help? Or is that more about putting a damper on all the ideas?)

Woodring: One thing that makes this kind of work worth the effort is the privilege of being able to play at the water’s edge. Every other job I’ve had required me to delve deeper into the madness of the world; this one demands I look elsewhere. I like the simplicity of the tools. Taking a pencil and a composition book to a quiet spot and exploring your own mind, bringing fragments of unconscious systems to the surface for repurposing as art… It’s such a real thing to do. Meditation definitely helps; if nothing else it strengthens the ability to concentrate.

Paste: How much thinking do you do about clarity? One of the things that’s always impressed me about your work is how easy it is to follow what’s going on.

Woodring: Once the storyline is in hand, the stories are planned out to a fare-thee-well with clarity foremost in mind. Because the stories are wordless it’s necessary to go the extra hundred miles to make sure everything is easy to understand and follow…superficially, anyway. It’s so much easier when you can have a little panel header that says, “Next Morning….” In the Frank stories, it’s necessary to show the landscape change from night to dawn.

Paste: Again because they’re wordless, your books tend to be very synesthetic. Is that just a cause of the way you’ve chosen to make work or do you experience synesthesia yourself?

Woodring: No, I’m not synesthetic in any way. I wonder what that must be like. The Frank stories are wordless because they’re meant to be beyond time or place.

Paste: You were born in California, right? Have you spent your whole life there? How has it shaped you?

Woodring: I grew up in Los Angeles but have lived in and near Seattle for the past 30 or so years. Yes, growing up in California affected me profoundly, in a good way. It was glorious, really.

Paste: How did California affect you? What about Seattle? Are you determinedly a West Coast dude?

Woodring: The Los Angeles of my youth was a confluence of post-war triumphalism, a tech boom, the ascendency of youth culture, television, transistor radios, beatniks, surfers, hotrodders, air travel in jets, MAD, Muhammad Ali, The Beatles, going to the moon, optimism and exuberance. Gas was cheap, like 17 cents a gallon; for a dollar you and your pals could hop into the old Dodge and drive to the beach, the mountains, the desert, Hollywood. So there was this tremendous atmosphere of freedom, and plenty, and the clear understanding that you were living in a golden age of music, humor and culture in general. I grew up seeing the world through that lens.

Of course it was also a horrible time in many ways. The Cold War paranoia thing was really awful…it bent me for life. I grew up in Burbank and Glendale. Both were lily-white at the time, especially Glendale, which at one point had a sundown law. If I saw a Black person on the streets of Glendale I knew they worked for someone there or were just passing through. Institutionalized racism was a relentless sour note that contaminated everything.

And of course it was fashionable during the ‘60s for fathers and sons to hate each other’s guts.

But I was a dreamy, fucked-up and contemplative youth, and I mostly sought to work out my problems in private. One great stroke of luck was that near my house was the magnificent Brand Library, my solace and refuge. That was a great thing.

I loved living in Seattle while we were there. It’s changed in the past five years.

Poochytown Interior Art by Jim Woodring

Paste: So you experienced hallucinations of a sort as a child? Do you still get them?

Woodring: Not for five years now. As an adult they mostly consisted of seeing radically distorted versions of real people. It was always a jolt but fun and intriguing to think about afterwards. Now I sometimes have half-awake hallucinatory lucid nightmares during episodes of sleep paralysis. Those are no fun at all.

Paste: What do you think stopped them?

Woodring: There is something not quite right with the way my mind works. I’ve always had perceptual problems, not being able to tell things apart, not being able to recognize faces, not understanding what I’m looking at when everyone else in the room can. As a kid I frequently couldn’t tell cartoons from real life, dreams from reality and so on. And I had a lot of experiences which fit into the hallucination/apparition category. Most of that confusion gradually got sorted out, but my mind still frequently fails to put things together in a reliable way. It’s slowed me down and messed me up my entire life. I am so sick of it.

A few weeks ago I was in a group of people and someone asked me out of the blue what language the ancient Romans communicated in. Well, I know full well it was Latin. But at that instant I had no idea, and I had no idea I had ever known. It was as if the idea had never been raised in my mind before. So I said,”Something somewhat like Italian, I would guess.” I must have seemed off-the-charts stupid to these people. It was embarrassing and painful in a way I know all too well.

My latter-day hallucinations were mostly misreadings of real situations. One of the most recent was in Seattle; I looked out the window and saw Thomson and Thompson from Tintin, real people but in grayscale, walking with what looked like a nine-foot-tall hooker in fuschia hotpants and python thigh boots. I watched them walk down the block towards me for about 10 seconds, crystal clear in every detail. I thought they was absolutely real and I was trying to figure out what they were got up for. When they passed out of sight and I went to another window to see them they were a mother and her two children.

As to why they’ve stopped, I don’t know. Just another thing dropping away with time, I guess.

Paste: How long does it take you to draw a single page? Is it physically taxing?

Woodring: I can draw a simple page in a day if I’m on my game. I probably redraw one page in 10. It’s not taxing but it can get a bit tedious. I stand at the drawing table, which goes up and down with a hand crank, about half the time. That makes a big difference in how I feel at the end of the work day.

Paste: Your work often reminds me of woodcuts. Is that deliberate? Or just the way it comes out?

Woodring: That’s not intentional at all. I just wanted it to be lush.

Paste: Do you listen to music or anything while you draw?

Woodring: I listen to spoken word: podcasts, old radio shows, documentaries, movie soundtracks, philosophical discourses and so on.

Paste: What kind of art do you consume in your spare time? Do you have an inclination toward psychedelic art? Or do you get enough of that from your own mind?

Woodring: I’m always looking for an artistic road-to-Damascus experience, so I look into everything. Psychedelia per se doesn’t interest me much unless it has a perceptible and simpatico agenda.

Paste: What’s given you that feeling? That’s such a good way to describe it. I feel like that’s what we’re all looking for, and 99.9 percent of art doesn’t deliver it.

Woodring: The major one was a 1968 Surrealism and Dada show at the L.A. County Art Museum; I had no idea. Then R. Crumb’s work; Fellini’s Satyricon; Eraserhead… a few other things.

Paste: Do you know Gary Panter? Because y’all seem to have a sort of Matisse-Picasso artistic relationship. There is a kind of very serious investment in the value of naivety that comes through in both of your work.

Woodring: I’ve met him a few times but don’t really know him. I admire his work tremendously, of course.

Paste: When did you start working on this book?

Woodring: That is a difficult question to answer. When I began Congress of the Animals in 2010 I made the stupid, stupid decision to modify the received (i. E., authorized) storyline and take Frank out of the Unifactor for the first time; and then I had the catastrophic notion to have him find a mate. A horrible, horrible struggle to write Congress ensued. It took me a year to concoct the sequence of events; the Unifactor made it as difficult for me as it could, but I persevered and dragged the character Fran into Frank’s world by the ears.

When the book was done I realized my mistake. In all previous Frank stories he awoke with the dawn, jumped out of bed and ran outside to explore and experience the mysteries of the Unifactor. Now that he had a companion he no longer felt that drive; he was inclined to sleep in, hang out with his love interest and be indolent. He would have degraded to the point of watching superhero films if this state of affairs had continued.

So Fran had to go. The Unifactor told me exactly how to do this in a way that not only took Fran out of the equation without insulting her but undid everything that had happened in Congress. That book was called Fran. When I started Poochytown I was obliged to redraw the first six pages of Congress of the Animals line-for-line as penance and to demonstrate that the events of Congress and Fran, if they actually happened at all, were no longer relevant. Whether those episodes actually exist or not is a question I can’t answer. In any event, from here on out the Unifactor is the boss of me.

So, you could say I started what became Poochytown in 2010, went badly off the rails, and returned to it in 2015.