Breaking in Your Writer Boots, Part I: Tini Howard on How To Become a Comic Scribe

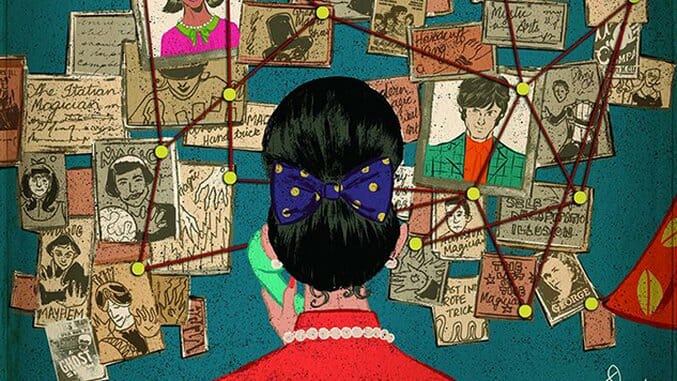

Cover Art by Devaki Neogi Comics Features Tini Howard

A few months ago, the Paste Comics team received a tragic email: Tini Howard would no longer be able to write under the auspices of editorial objectivity. Of course she couldn’t—the weekly Required Reading contributor had not only announced her new series, The Skeptics, with artist Devaki Neogi, but was also scripting Mighty Morphing Power Rangers: Pink and had stories lined up with Gerard Way’s new imprint at DC Comics, Young Animal. And those were only the projects she could formally announce. She had evolved from a writer about comic books to a writer of comic books.

But though she could no longer comment on the work of publishers she wrote for, Tini also had hard-earned insight into an industry whose landscape is in the midst of huge changes. She’s been vocal on this very site about the necessity for views that transcend those of the straight white dudes who tend to dominate creative teams, and she’s currently shaping that change through comics that can be bought in stores right now.

So we asked Tini to recount her trajectory and give any advice to future comics writers about what it both means and takes to be a professional sequential arts scribe today. ![]()

Writing about the secret of your success is a weird thing, when you aren’t sure if you’re successful yet.

Truth be told, navigating a way into the professional comics world is something of a strange quagmire. I think it was Brian K. Vaughan who related breaking into comics to a leak in a house, or a weakness in a wall—once you find a way in, that way gets repaired, and you can’t go that way anymore. So think of us like cockroaches, desperate and hungry.

So, I’ve returned to my pals at Paste to talk about how I found my way into the metaphorical house to eat metaphorical cardboard and lay my metaphorical eggs:

I read comics my whole life before I understood that you could write them if you didn’t also draw them. I’m not terribly proud of this fact, but I share it in order to give others hope. You can start out with a really big love for comics and not much else.

I’ve always been a writer. I’ve always read comics. I do not know why it took me about 25 years to put two and two together, but I was slogging through writing a lot of short stories that no one wanted to publish, imagining them in my mind as great graphic novel adaptations someday, until I figured this one out. They always say “you don’t need permission to make comics,” and you don’t, but I was at a disadvantage, not at least getting how the sausage was made.

I think it’s worth mentioning that I was in my late teens before I first stepped into a comic shop. And even then it wasn’t to buy comics. Many of my early comic shop experiences were related to my gaming experiences. I’ve been a player of tabletop RPGS—think Dungeons & Dragons—since before writing comics was even a twinkle in my eye. This is relevant, especially in a field where most of the men in it can say they’ve been drawing Spider-Man their whole lives, or when asked, at age seven, what they wanted to do for a living, they said, “write Batman.”

Here’s the thing: I wanna write Batman too, but my seven-year-old self didn’t know that was possible.

In my late 20s, I had a quarter-life crisis. I’d been working a series of upward-growth jobs at the same Very Good Company for about five years, and had reached something of a turning point. A boss sat me down and explained that I’d need a degree to progress further—more money, more responsibility, more perks. All of those good things. The company I worked at offered a tuition coverage program, meaning they’d pay the bills for me to get a degree in whatever relevant field they wanted me to work in—marketing, in my case—and then I’d continue to work there for as long as they felt was fair, having paid for my degree. All in all, it meant committing to another 10 years at this company. I’d be nearly 40 before I could look for a new job.

Needless to say, I didn’t take that route.

This is relevant, because one of the most common things professional comics writers like to tell the aspiring is that “there’s not much money in comics.” There isn’t, but if you’re lucky and smart, there’s enough to live on, and plenty of really awful jobs can’t even promise you that. Don’t get me wrong—everyone should be fairly compensated in comics. I’m not an advocate of the idea that a cool job should be volunteer work, I’m just pointing out that most jobs suck and you’ll struggle with money your whole life anyway.

If I’d cared about the money thing more than the happy thing, I’d have gone with the indentured-servitude-of-marketing route, is what I’m saying.

So, with the perfect storm of dissatisfaction and dreaming, I began writing scripts. Bad ones! A feminist Captain America knockoff I oh-so-cleverly called The Impenetrable Suffragette—get it? I started collaborating with my artist friends on little things that didn’t get past a page or two, but they happened. I made Facebook pages (I know, I know) for entire series, graphic novels that didn’t happen. But I still collaborate with the artists, talk to friends I made and, most importantly, I got practice, and a decent idea of what went into writing a script. This was important knowledge to refine as I pitched to multiple anthologies, getting plenty of rejection letters.

I read a lot of blog posts from guys like Jim Zub and Matt Fraction, who talked about reverse-engineering comics pages they liked, or posted chunks of scripts for the completely uninitiated. And I read a lot of advice that said just make comics. And so, when I went to a convention with tables and tables of amazing artists and my very own homemade business cards, I walked up to a lot of them and simply said:

“Hi, I’m working on a comic and looking for an artist and I like your work.”

A lot of them just stared at me and went back to drawing. Yep! That happens. But the two that were actually nice to me, for some unknown reason, were Eryk Donovan (Constantine, Memetic) and Meghan Hetrick (Red Thorn, Batman Eternal). While neither of them were working on those books back then, they were both incredibly good artists and also friendly to folks who stopped off at their tables, making it unsurprising that they’d be successful in this business. We didn’t end up making a book together, but I kept in touch.

All this convention-going and emailing, rejection-letter-getting and script practicing—what it meant was that I felt I had a pretty good idea of what not to do as I went into the Top Cow Talent Hunt contest in 2013.

Check back next week as Tini discusses her first time working for a comic book publisher and whether or not she still has that kick-ass Batman shirt from when she was seven.