Cocktail Queries: What Is Sotol, and How Is It Different from Tequila and Mezcal?

Photos via Clande Sotol Drink Features cocktails

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

If you’ve had your ear to the ground in the spirits and cocktail world in the last few years, you’ve probably noticed the term “sotol” beginning to rise to prominence. Fans of tequila and mezcal in particular are likely to be most familiar with sotol, because it shares some of the same background and methods of production, and is likely to be consumed in the same spaces. But although sotol is another traditional Mexican spirit—it’s actually the state drink of Mexican states Chihuahua, Durango, and Coahuila—it’s also an experience all its own. Made from an entirely different plant than the likes of tequila or mezcal, sotol is a vivacious, eye-opening flavor bomb that is making some serious inroads among the American liquor cognoscenti. It’s entirely possible that within a few more years, it will have made the same emergence in the American cocktail scene that mezcal made in the 2010s.

But what is sotol, really, and what differentiates both its production and its flavors from the likes of tequila and mezcal? Allow us to offer a crash course in this traditional spirit.

Like tequila and mezcal, the sugars used to ferment (and then distill) sotol come from the cores of a common desert plant, but rather than any species of agave, sotol is made from … sotol, which is also the name of the plant. The “desert spoon” is a plant with many species and names, with sotol liquor commonly being made from the likes of Dasylirion wheeleri (desert spoon, spoon flower, sotol, common sotol) or Dasylirion leiophyllum (green sotol, smooth-leaf sotol, smooth sotol). They’re flowering succulent plants in the asparagus family, with long, thin, spiny leaves that make the plant overall look quite like a spiny sea urchin. Varieties of sotol grow throughout Northern Mexico, commonly found in the deserts of Chihuahua or forests of Oaxaca, but the range of wild sotol plants also creeps into the U.S. in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. As a result, sotol is potentially both a Mexican and American spirit, though the tradition of sotol production in Mexico goes back much farther into the past.

Nor does the sotol plant really taste much like agave—rather than the sweetness and fruitiness common to most species of agave, sotol plants tend to have more evergreen-like, resinous or grassy characteristics. Speaking with Wine Enthusiast, Ricardo Pico, co-founder of Sotol Clande, said the following regarding the flavor of different sotol species.

“The most important factor is the terroir. In the forest, we get more rain and have different vegetation. Some of those sotols will have menthol, eucalyptus, a very fresh taste like mushrooms or pine.”

Thus, different sotol plants grown in different climates tend to produce quite different flavors when used to make a spirit. As Pico suggests, sotol of wetter climates has more “fresh” characteristics of resin, grass and mint, whereas sotol from drier climes often reads as more spicy, leathery and earthy. These are only broad generalizations, however, and the many species of sotol are capable of producing many different and unique flavors.

Mexico’s excellent Clande Sotol actually color codes its batches based on which of its distillers produces each product, in a variety of different ways.

Mexico’s excellent Clande Sotol actually color codes its batches based on which of its distillers produces each product, in a variety of different ways.

As for how sotol is made, the process will sound quite familiar to the mezcal geeks in the house. The cores of sotol plants are roasted in underground pits, fired by whichever type of wood is common in that region. This again means a difference in flavor, given that oak smoke and mesquite smoke can be quite different from one another, although the smoke flavor in sotol typically seems less pronounced than it is in many mezcals. It takes several days of this slow roasting for the sotol plants to break down and release their sweet, sticky sap, which is then fermented with wild, native yeast in wooden vats, before being distilled in copper or stainless steel pot stills. The vast majority of sotol is then consumed without wood aging (listed as joven), though reposado and anejo bottlings do exist, just as they do for tequila and mezcal. In a way similar to those categories, though, many of the sotol purists seem to view the unaged sotol as the “true” version of the spirit, unadulterated by the smoothing influence of oak barrels. It is certainly true that the unaged sotol gives by far the strongest impression of terroir.

In an era where tequila and then mezcal have gone through massive sales booms in the U.S. market, it’s only natural to expect some proportion of those customers to continue on down the path of similar spirits until they discover sotol. Some analysts have predicted that the agave shortage of the late 2010s—which led to younger plants often being used in tequila production, and a reduction in the quality of many tequilas as a result—would lead to more brands experimenting with sotol due to its widely available nature, though the massive planting of agave in recent years suggests that the industry may see a whiplash, with agave becoming overly available by 2026 due to the amount that has now been planted.

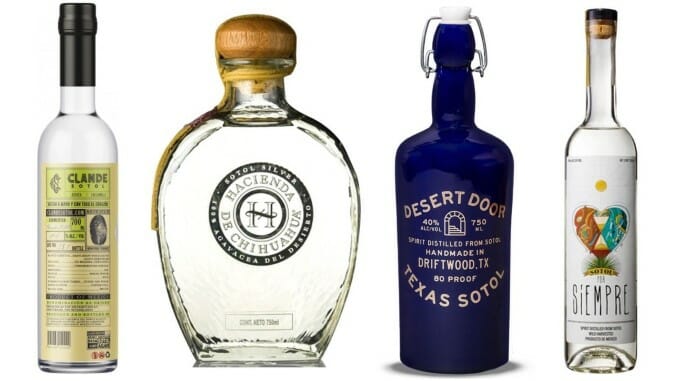

Regardless, various commercial sotol brands from both Mexico and the U.S. have been steadily gaining traction in the U.S. market, often via cocktail bars and restaurants with extensive agave spirits menus. Currently available brands include the likes of Sotol Clande, Hacienda de Chihuahua, Sotol Por Siempre and the Texas-based Desert Door Sotol, which is made entirely with U.S.-grown plants.

I still haven’t had an opportunity to taste a ton of sotol, as availability can be limited depending on one’s location, but the brands I’ve come across such as Clande Sotol have been singularly fascinating to my taste buds. Bright, herbaceous, saline, fruity, chemical, resinous, smoky, rich—I’ve taste it all in sotol, and often many of these at the same time. In terms of the experience of exploring sotol after developing a taste for tequila or mezcal, I would compare it to developing a fondness for the funkiness and earthiness of rhum agricole after first appreciating traditional, molasses-based rums. All in all, it’s a category I can’t wait to sample more of in the future, and I look forward to seeing sotol gain more awareness in the years to come. If you’re an adventurous drinker looking for the next great frontier, reach for a bottle of sotol and you likely won’t be disappointed.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.