As the daughter of first-generation Chinese immigrants, I used to take pride in pooh-poohing Americanized versions of Chinese dishes. Turning my nose up at cardboard cartons of chow mein and holding up a plate of slimy sea cucumbers, I would tell myself that I knew what real Chinese food was, and it was better.

That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy eating the crispy fried chicken cubes drenched in sticky sweet orange sauce from time to time. But I never acknowledged it as Chinese food, and certainly not of the authentic variety.

It wasn’t until recently that I stopped and asked myself what exactly it was that I took so much pride in. What does “authentic” Chinese food really mean?

Many Americans perceive ethnic food to be an inferior cuisine, based on the expectation that it should be cheap. This kind of thinking often arises out of ignorance – a misunderstanding that Chinese dishes are simple, consisting of inexpensive ingredients and prepared in a rudimentary style. Things are slowly changing these days, with more and more foodies becoming interested in regional Chinese specialties, even prompting the Wall Street Journal to declare that, “when it comes to fine dining in America, Chinese is the new French.” And yet, foodies are still unwilling to shell out the same amount of money for Chinese soup dumplings as they would for a French duck.

The widely-held belief that Chinese food is just plain bad for you is yet another false expectation of what authentic Chinese food should be. Recent restaurant reviews confirm that the words “greasy” and “unhealthy” are unfortunately still very much synonymous with Chinese cooking, and the xenophobic myth that MSG causes illness remains prevalent among many white Americans.

But what many Americans believe to be authentic isn’t really authentic at all. Indeed, the birth of Chinese food in America resulted from years of racist attitudes towards the wave of Chinese immigrants arriving during the 1800s. Opening up restaurants was one of the few ways the Chinese were allowed to stay in America, and soon Chinese chefs began to tailor their recipes towards the prevailing sweet American taste buds. And so the Chinese food Americans are familiar with is actually either just a miniscule fraction of what makes up Chinese food culture, or would not even be found anywhere near mainland China.

Growing up in America, I often felt caught between the Chinese food my parents served at the dinner table, and the Chinese food being sold in restaurants all over the country, as if those were the only two options available to me. When I started to reclaim my Chinese identity and cultural heritage as an adult, I realized that I needed to discover what authenticity meant for myself.

For a long time, I adhered to this vague notion that authenticity referred to purity – that true Chinese cuisine could not be tainted by foreign influence. Down with the beef and broccoli myth of America!

But I quickly realized that this definition was much too simplistic. Take General Tso’s chicken, for instance. It’s one of the most popular items on any Chinese takeout menu in America: crispy, fried chicken in sticky brown sauce surrounded by broccoli. Completely irresistible, and not remotely authentic, right? But trace its history far back enough, and you find that the dish was invented by Peng Chang-Kuei, a chef born and raised in Hunan, China. He conceived of the dish in Taiwan in 1949, naming it after a Hunan general and highlighting traditional Hunanese flavors. When Peng Chang-Kuei later opened a restaurant in New York in the 1970s, he made the dish sweeter and less spicy, and Americans flocked to his restaurant in droves.

Does the fact that a Chinese chef created General Tso’s chicken excuse the dish from its American influences? Can’t this adaptation be seen as a subset of Chinese cuisine – made by Chinese, for both Chinese and Americans?

Upon closer examination, the idea that authentic Chinese food must be free of foreign influence falls apart pretty quickly. Foreign imports arrived as early as 3000 BC, when the Middle East introduced wheat and barley to Chinese agriculture. The Mongolian conquest of China in the 13th century saw the introduction of hot pot-style cooking. And in the 17th century, Portuguese traders brought New World crops to China, among them tomatoes, sweet potatoes, and peanuts, ingredients common to so many dishes found in China.

A more contemporary example might be MSG, the chemical additive used as a flavor enhancer in much of Chinese cooking. It, however, wasn’t discovered until 1907, and by a Japanese chemist no less. Later on, Chinese chemist Wu Yunchu reverse-engineered the compound in order to secure China a top spot in the MSG global market.

And let’s not forget that China is an incredibly vast country with provinces that run the gamut of differing climates and terrains, each province developing their own unique style of cooking with their own local ingredients.

It’s become apparent to me now that cultural cuisine can’t be strictly tied to which crops are local and which are not, or by how pure the food is from foreign influence. Perhaps authentic Chinese food cannot be boiled down to a single location, ingredient, or style. To me, authenticity is no longer about expectations, or a list of criteria; in fact, it has come to mean the very opposite. Authentic Chinese food should surprise you, and it should also comfort you. It’s the dish tucked away in the corners of distant provinces, and it’s the dish that Chinese mothers pass on to their daughters.

I looked back at some dishes in my mother’s repertoire, among them crunchy pig ears, pork and chive dumplings, and one of my absolute favorites, sweet and sour fish with broccoli. And then I realized that my mother was doing just what other Chinese chefs, chefs from any nationality really, have been doing throughout history: preserving tradition, while adapting to the times. Because she would always prepare the fish just the way I liked it.

Although this country was founded upon immigration and extols the ideals of cultural exchange, it is often very hard for the voices of the minority to be heard. Foreign food can easily be misconstrued as either exotic and fancy, or dirty and cheap. But because we all have different experiences with the food we eat and what they mean to us, America would be all the better for approaching foreign cuisine with respect and an open mind. Take the time to understand where that plate of dumplings or that bowl of noodles came from, what they mean to the people who made them, and appreciate the fact that in the land of opportunity, authentic food can be found right around the corner.

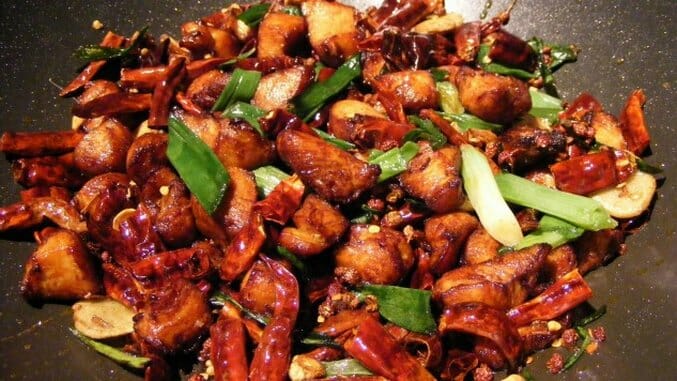

I take comfort in knowing that whatever happens, my rich, culinary heritage will endure in some form or another, be it braised sea cucumbers, or orange chicken. My only hope is that we are given the opportunity to speak for our food and our culture, and that Americans are willing to listen respectfully between each bite of stir-fry, down to the very last grain of rice.

Elena Zhang is a freelance writer based in Chicago. Her writing can be found in HelloGiggles, Bustle, The Mary Sue and PopMatters, among other publications.