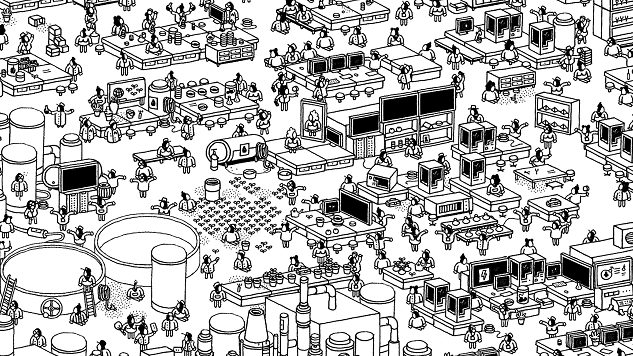

You only need to play Hidden Folks for a few minutes to discover how blissfully joyful it is. Similar to the popular Where’s Wally / Waldo? puzzle books, it has you scan hand-drawn landscapes to find certain characters and objects hidden inside. The task gets harder as the size of the canvas grows and becomes more densely populated, moving from jungles to farmlands and eventually bustling cities. It’s not always enough to use your eyes, however, as the game makes use of its interactive format to better hide its targets: tents need to be opened, trees shaken and treasures dug up.

Beyond the game’s rich illustrations, which were all drawn by Dutch artist Sylvain Tegroeg, the feature of the game that’s most likely to charm you is its sound. It’s not the fact that everything in each scene makes a noise when interacted with, whether it’s a monkey yelping or grass rustling, it’s that every single noise is a silly mouthsound.

“The first time I used my voice to add sounds to anything were some experimental videos my girlfriend had made,” says Hidden Folks designer, Adriaan de Jongh. “The videos featured solely inanimate objects, and I added my voice to them in a way that gave them character. It was tremendously silly, but we laughed really hard at it and did it again with a few other videos later.”

De Jongh repeated the mouthsound technique while making a Global Game Jam entry with friends and, in his words, “accidentally won the Best Audio Award” for it (“accidentally” as it was intended as a joke, not a serious effort). “This was around the time Sylvain and I started adding more basic features to [Hidden Folks], and I borrowed some of the sounds I had recorded in that game jam,” de Jongh says. “I thought it was kind of funny. Sylvain thought so too, and we decided to stick to it!”

The sound design epitomizes the playfulness of Hidden Folks, which it was recognized for before it was even released. It won the BIG Indie Pitch at GDC 2016, was a nominee in the Google Play Indie Game Contest, and was among the official selections at Day of the Devs, Indie Megabooth and Fantastic Arcade. That playfulness is seen also in some of the character animations, one of which recreates de Jongh’s signature dance, which he’s all too happy to launch into when making fun of himself at places he deems too serious. “Think about business meetings! Those need more dancing,” de Jongh says. “Dancing itself isn’t so much part of my life as the playful attitude that comes with it. I am super inspired by the writing of my hero Bernie DeKoven.”

It could be argued that de Jongh is a new-age version of DeKoven, who was involved in the New Games movement of the 1970s, and has served as a fun theorist and game designer in the decades since. Like him, de Jongh aspires to design meaningful fun into everything he makes, which is precisely why he was chosen as one of the Forbes 30 under 30 in 2016. This desire grew out of the ennui he experienced when growing up alongside his two younger brothers and sister in Wilnis in the Netherlands, which he describes as “an extremely boring village aside from that one day our dam broke.”

The first eight years of his life were spent building treehouses out of leftover pallets from the local winestore, and driving around in a skelter a lot. “After that I got kind of hooked on a few games: Commandos, Age of Empires, Team Fortress, and later World of Warcraft, to name a few,” de Jongh says. “Went to high school, had an absolutely terrible, terrible first two years—I was very heavily bullied—and around the time I turned 15 I had been playing World of Warcraft every evening for the last two years and it started to bother me that it was sucking up so much time.”

This was the first time that de Jongh was really drawn towards engineering social play. He wanted to get away from the electric hum of the computer screen and yearned to be outside and around other people. This desire is what has come to define his life as a game designer and what has earned him his many accolades. But he didn’t realize this until after graduating the Game Design & Development course at the Utrecht School of the Arts as the youngest student in his class, at the age of 16. After that he took up a game design internship at the Dutch game studio W! Games (now ForceField VR), where he met senior designer Kent Kuné.

“At some point [Kuné] started bringing prototypes to the office, pretty much every day. Prototypes he had made in Unity3D the evening before to exercise his game design and to learn a bit of programming,” de Jongh says. “He had coded fully-functional networked multiplayer games or crowd simulation games in a single evening! I saw that and realized that was exactly what I wanted to be able to do: to code enough to bring my own ideas to life, and iterate on them.”

De Jongh started working towards this goal in the months following his internship, at the age of 18, picking up Unity3D to make his own games using the tutorials and following advice from people in the Unity forums. “I was very disciplined in picking up programming; you could say more than the average person,” de Jongh says. “Those three months of learning to code ended with my first burnout. I found learning to code exciting and that it was all I wanted to do, and as a result I kind of stopped doing the stuff healthy people need to do, like exercise and eat healthy.”

After spending the post-World-of-Warcraft years being super sporty, playing football, baseball, tennis, and doing judo and horse riding, he found the hours of sitting in a chair that programming games required messed up the lifestyle he enjoyed. Finding ways to have the best of both of these opposing worlds has encouraged de Jongh to experiment over the years. “To fix the ‘sitting’ part I have a permanent standing desk with a high stool, and the idea of a permanent standing desk is that the ‘default’ way of working is standing as opposed to sitting,” he says. “I can still sit on the stool, but at least I’ll start standing, and that will force me to go back and forth throughout the day.”

“To fix the ‘still’ part, I need to get off the computer regularly, and for that I have an alarm that goes off and takes over my computer for two minutes, forcing me to step away,” de Jongh says. “This gives me only a little bit of movement, so ideally I exercise every other day. I’m currently into running and bouldering, which give me a good combination of muscle fitness and endurance.”

He has taken these practices further in the past by switching up his work rhythm. “At the peak of my experimentation I worked only on the even days of the month, resting on the other,” de Jongh says. “A work day meant 15 hours of undisturbed productivity; a leisure day meant extra sleep, amazing food, and a lot of exercising. After doing this for a whole year I quit because… well, it was just too incompatible with the rest of the world.”

That penchant for experimentation and physical activity has carried over into the games de Jongh has designed. It started when he showed his friend Bojan Endrovski one of the prototypes he made for his graduation project, which was about social interaction in games. The pair decided to turn the prototype into a full game and publish it on the App Store “just for the experience alone.” But to do that they needed to be a legal entity, and so they founded Game Oven, and immediately landed on the studio’s first hitThe prototype became the cooperative mobile game Fingle, which encourages players to lock hands and get intimate to complete the tasks on the screen. “To make a longer story short, we didn’t expect Fingle to do as good as it did, and it basically funded our studio for five years,” de Jongh says.

After Fingle, de Jongh developed even more of an interest in games that facilitate social interaction that goes beyond the usual “couch games” or “local multiplayer games.” He had grown tired of “the dynamics between winners and losers” that these social games were built to serve. “I wanted to make games that were social in ways that you didn’t quite see in videogames. Think about the social interactions when people are having sex, or going out to dance, or the interactions people have when they are just talking to each other; there are thousands of little interactions to be inspired by and where one could make a game out of,” de Jongh says.

It’s this thinking that led to Bounden, a game that uses smartphones to turn players into dancing partners. The game requires both players to hold onto either side of the phone, and then to twist and twirl to match the dance steps shown on screen, which were informed by the expertise of the Dutch National Ballet. Bounden won awards for its innovative design at various shows, including Games for Change and the Dutch Game Awards.

“I found the process of finding those [social] interactions and trying to come up with a videogame around that to be exhilarating, and to continue to be able to go through that process was really my personal goal,” de Jongh says. Unfortunately, his Game Oven co-founder Endrovski wasn’t so enamored by this pursuit, and while he was happy to explore that space for five years, after that the interest waned. Those diverging interests, along with the various struggles that come with running a company as de Jongh outlined here, led to Game Oven disbanding in 2015.

Life after Game Oven has been “as amazing as it has been rough” for de Jongh. He’s been able to buy a house and prototype various games that please him, but at the same time he’s had to do house renovations, single-handedly do the coding and marketing for Hidden Folks, and try to stay healthy while doing it. “When we closed Game Oven, I thought I would be able to make games in a much more relaxed way, but Hidden Folks showed me that my passion for making games can consume me wholly,” de Jongh says. “Funny enough, working so hard on Hidden Folks has isolated me as much as World of Warcraft did back in the day. I don’t like it and I crave for more social interaction. I probably won’t quit making games, though, but I will turn the knobs back a little so I can breathe a little and hang out with my friends again.”

Now that Hidden Folks is out, de Jongh can rest a little easier, but he’s already hard at work on expanding the game with new areas that are larger and more complicated than those currently available. “The thing I’m most excited about … I can’t talk about right now,” he says. “Because the feature is a huge technical challenge and I might not be able to pull it off. You’ll have to trust me when I say that when I release it, it will make you come back to the game!”

After that, it seems de Jongh will return to the prototypes he previously mocked up to see if they warrant developing further. “I currently have one prototype of a game that is by far the most fun game I’ve ever made, but it doesn’t ‘click’ business-wise, so I won’t turn into a full game until I find that one thing that makes it click,” he says. His current batch of prototypes follow his interest in folk games, which he loves because they can be about outsmarting each other, touching each other, learning each other’s boundaries, and finding new ways to love each other.

“I wish videogames would explore these territories more, and I am actively prototyping for games within this space,” de Jongh says. “Trying to shape the social dynamics of folk games into a videogame is really hard, though! It constantly feels like I’m reinventing the wheel.”

“I naturally ask myself ‘why make a videogame and not a folk game?’ and what I answer to that is that the barrier to start a videogame together with my friends still seems lower than the barrier to get people to meet at on a grass field for a few folk games,” de Jongh says. “Videogames are a convenient and ‘safe’ way of getting into any game—virtual or not. My goal then turns into: how do I make a videogame ‘unsafe’ again?”

Chris Priestman writes about videogames, internet culture, and digital art. He’s written for The Guardian, Edge, Kotaku, VICE, Gamasutra and many more. You can find his work at chrispriestman.com and follow him on Twitter at @CPriestman.