It feels like, at some point during The Crew’s development, its designers lost sight of the fact that people like to drive. Not just to race or to bash through crates or to launch from jumps, but to drive. People like those other things too, of course, but underlying those joys is a more fundamental one: People like to move, to travel, to drive. Unfortunately, The Crew is not a good game for driving. I didn’t realize that right away though. On my first night with The Crew, once I was done with the tutorial missions, I decided to travel from Detroit to New York, and then down home to Jersey—or at least to the approximation available in this strange pastiche America. I put on a podcast. I drove.

I passed through so many little places, the sort we all have in the periphery of our lives. This is when The Crew is at its best. It so easily captures the grimy little motel off the side of the highway that you crashed at that night. Or the little café, with that patio that you remember so well, but that you can’t actually remember stopping at. Or that little park with the statue of… um, you know, that guy? These towns are filled with low resolution assets and weird architectural arrangements, but somehow that makes them more familiar. Whether they intended to or not, Ubisoft captured the way small towns, strange signs, and old highways feel in my memory. Hours slipped away.

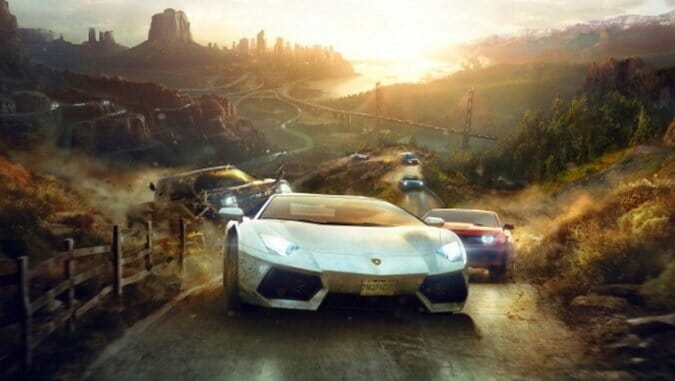

The big cities I passed through didn’t feel as good as the spaces in between. They were cramped, desperate to show off landmarks. But still, that first night I thought I was going to love The Crew. It had given me something no other game had: A sort of Postcard America. The kind of virtual tourism I could feel good about. The open road. Little sketches of little places. The warm feeling you get when you “discover” a quaint little town, but with none of the awkwardness of being an outsider.

But by the end of my time with it, I realized that I hated The Crew. There’s so little in its structure to encourage the sort of aimless wandering that I loved that first night. The driving model, which was perfectly fine for quiet exploration, fell apart when applied to the campaign’s missions. Those missions (and the laughable cutscenes that stitched them together) were a burden I couldn’t wait to be done with. And the game’s difficulty curve and progression system encouraged me to fast travel from event to event, grinding so I could get the upgrades I needed, and missing out on all those interesting places. Most of all, though, it made me realize that I didn’t want a Postcard America at all.

The Honeymoon’s Over

Like every other recent Ubisoft release, The Crew is stuffed with a huge array of activities: Story missions guide you through the life of Alex Taylor, an ex-con turned undercover cop out for revenge. Faction events offer asymmetrical PVP, with your race times and mission performance adding to your team’s score. Skill missions dot the roads, testing your driving ability through various mini-games and awarding you with new car parts. These are added to your map naturally as you explore, or you can add them in bulk by finding and approaching the satellite dishes (which serve as The Crew’s small variation of the “synchronization towers” common to Ubisoft’s ur-design) and once they’re added you can fast travel right to them.

As Alex Taylor, you’re tasked with infiltrating the 510s, a country-wide gang that does ambiguous crime stuff and organizes itself around a hierarchy of skilled drivers. The Crew so clearly wants to evoke the frenetic chase scenes of The Fast and the Furious, but it never really comes close. Every mission fits into a handful of types, so the whole thing ends up feeling formulaic. Sometimes you bash through 80 crates in Nebraska. Sometimes you bash through 80 crates in Nevada. Sometimes a plane or a helicopter will take a really low route across the skyline; not because it’s connected to the mission, but because it’s a cheap way to inject a feeling of speed and scope into the missions. And unlike The Fast and the Furious, there’s none of that Vin Diesel charisma here: Alex Taylor and his “crew” are flat archetypes. If you listen closely, you can even hear the resignation in their voices.

The other reason that The Crew falls short of Hollywood spectacle is that it clings to the ambiguity of what exactly you’re doing. Since you’re working undercover most of the missions you do involve some sort of criminal activity, but there’s rarely any sort of specificity. And there’s never any real human cost. You smuggle things, sure, but you promise “never to smuggle anything dangerous.” Cop cars stutter to a stop, but they never explode. The number one crime you’ll commit—literally the only thing that will draw the ire of the police—is the destruction of fences. The Crew is an action film that only ever airs on TBS, with a zero body count, and all of the curse words dubbed over. The Crew is Postcard America.

This Year’s Power Fantasy

As you travel from one campaign mission to the next, you’re theoretically meant to play through the “skill missions” that dot the highways. They neatly layer over the road, and test your ability to control your car, take jumps, or navigate tricky routes. On paper, they’re a great way to encourage the sort of exploration I loved that first night. Unfortunately, the The Crew’s difficulty curve and progression system encourages you to quickly fast travel from event to event, from skill game to skill game, cutting up the game’s impressive world into boring little chunks.

These events lock into a progression system to encourage players to gorge themselves on this buffet of content. As you play through events you gain experience points and new car parts. Leveling up nets you bonuses to your driving stats, discounts to shops, and other benefits. Pretty standard stuff. The parts system, on the other hand, is the most insidious design to come out of one of Ubisoft’s many dev houses.

When you buy a car in the The Crew, you attach a certain “kit” to it. A “street” kit makes it great for drifting your way through cities. A “dirt” kit means it’s a solid all arounder, but really excels when it’s going off the paved road. The kit comes with a pre-leveled set of parts, but you’ll quickly need to upgrade them if you want to keep pace with the new events you unlock. Each part has a list of attribute scores for things like acceleration and grip, but whenever you get a part as a mission reward, all of that is streamlined down to a single number: Its impact on your car’s level.

These numbers—all of them—are absurd. Those new tires might increase your Mustang’s level from 498 to 510, even though they drop the braking to 4332. I like to imagine conversations in this world: “Damn, man, what’s the acceleration on that thing like?” “It’s got a clean 6055 Accelerate, and a Top Speed of 4426.” “Woah.” Taken by itself this system is just a little awkward, but then it hooks into the game’s driving model and it becomes something much worse.

When you begin The Crew with your lowly starter car, the driving is painfully unresponsive, floaty, and slow. It’s hard at first to know where the problem lies. Are you just bad at this? Did you pick the wrong starter car? You do a few more events, grinding away, unlocking more parts, maybe buying a new car and a higher level starter kit. And then it’s 15 hours into the game and you suddenly feel like you’ve got it. You take those turns better, you drive the racing line perfectly. It’s easy to wind up patting yourself on the back for your improvement.

But it isn’t you, not really. It’s that level 42 suspension, those +300 grip tires. It’s such a carefully designed system, it’s hardly even noticeable at first. No single part changes things that dramatically, so it really feels like you’re mastering the mechanics, improving as a driver. At least until you go back and try out one of those low level cars again. Then it all comes rushing back.

The Crew is a prime example of the new power fantasy. If, as Rowan Kaiser has argued, the old fantasy was about having power, the new fantasy is about accumulating power. The old power fantasy was invincibility codes and infinite ammo. The new power fantasy is the feeling that you’ve earned your success by your hard work alone. This is the fantasy behind the guitar-riff that signifies that you’ve leveled up in Call of Duty multiplayer. It’s the fireworks and orchestral bombast of Peggle. It’s the steady return on investment in Fantasy Life. It is a power fantasy that reflects our time. We want to be reassured that our effort will pay off in the end, that progress is guaranteed, and that our achievements are fully our own. I’ve never seen this fantasy executed as perfectly, so seamlessly as in The Crew. This is Postcard America.

Nothing Will Go Wrong

The thing is, the driving never really moves beyond serviceable even once you get that top level coupe. Everything bounces around weightlessly. The Crew is filled from coast to coast with animals—animals that harmlessly slide away from your car without slowing you down. Opponents do the same when they hit oncoming traffic, and at the press of a button, your own crashes become inconsequential, zipping you back onto the track—often in a better position than you were in when you wrecked. Because of this, neither winning nor losing is really satisfying. Losses feel cheap and victory feels cheaper.

All of this is at its worst in missions where you’re ordered to “take down” an enemy racer by hurling into them with your car. But even head on collisions are weak, tentative, and diffident. You chip away at a health bar, bit by bit, until the victory cutscene plays. There’s no energy here, no spectacular catastrophe, only slow and steady progress.

Understood historically, driving is a remarkable thing. We sit in little metal boxes and move twenty to fifty times faster than we walk around. And we do this on a cramped road filled with other people doing the same thing. Space transforms around us. Vast distances squeeze tight and neighborhoods grow into towns and towns into cities. And even though we know that people inevitably die (even when driving safely), we find a way to be comfortable in our cars. We sing along to the radio.

If I ignore the game’s structure entirely, I can wring this out of The Crew. It lets me barrel across the Mojave’s vast emptiness—it just goes and goes doesn’t it? The Grand Canyon stops my cross-country sprint, reminding me that we haven’t conquered nature so much as we’ve learned to put up with it. And there’s a breadth of experience here: As you move from region to region the architecture, the climate, and even the sorts of ads on the billboards change.

But The Crew is not Eurotruck Simulator for the United States. Even though they’ve meticulously crafted this sprawling space, they don’t seem to understand that there’s joy in these mundane places. That’s where the magic is, but The Crew thinks it’s a better idea to offer wide shots of fireworks and stadiums and bridges like a poor man’s Michael Bay film. But it’s not the second coming of Burnout Paradise either. It’s too staid for that. It’s just a clipboard and a list. You check off the boxes, read the little wiki entries on the landmarks, and continue on to the next assignment. Your progress is constant and assured (so long as the servers are up and the AI doesn’t cheat, anyway.)

I realize now that I wish that this game could make me feel like an outsider in a strange town: That feeling is America. And The Crew has none of the licentious anticipation for the fictional pile-up, nor any of the guilty pleasure of rubbernecking—American pastimes, both. The missions never just say “Get to Wyoming,” and then let me plot my own foolhardy, American route there. They don’t even let you look at the map. Just trust the waypoints and go.

And I never find myself singing along to the radio, wondering quietly in the back of my head what might go wrong. Nothing will go wrong. This is Postcard America.

The Crew was developed by Ivory Tower and Ubisoft Reflections and published by Ubisoft. Our review is based on the PC version. It is also available for the Playstation 4, Xbox 360 and Xbox One.

Austin Walker is a PhD Candidate in Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario, writing about games, labor and culture. He writes about games at @austin_walker and at Clockwork Worlds.