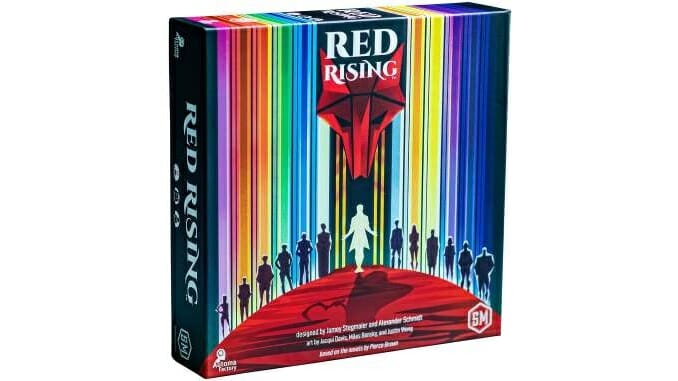

Change the Paradigm with the New Red Rising Board Game

Images courtesy of Stonemaier Games Games Reviews board games

Pierce Brown’s popular Red Rising series of dystopian novels, set in a distant, impossible future where humanity is organized into castes identified by colors, has now made its way to the tabletop with Stonemaier Games’ new release, also called Red Rising. It’s a surprisingly simple, elegant game, one you’ll probably enjoy a bit more if you know the characters in the books, but in no way requiring that foreknowledge to appreciate the game.

Red Rising is a game of hand management. You start with five cards, and you will probably end with five cards, with the goal of assembling the most valuable final hand you can. Each card in the deck is unique, representing a specific character from the books or a particular job, and thus each card has a color from the world of Red Rising as well. Each card has a base point value if it’s in your hand at the end of the game, but each card has an action associated with playing it, and most cards also offer some kind of point bonus (or even a penalty) if you have certain other cards or colors in your hand.

The board has four tracks that are supposed to represent four major locations from the Red Rising universe: Luna, Mars, The Institute, and Jupiter (hey, I said it was an impossible future). On a turn, you play one card from your hand to any of the four locations and use the action printed on the card. Then you take a card from any of the other locations, and get a bonus associated with that location. If you don’t wish to give up any of your cards, you can “scout,” taking a card from the deck and playing it instead. Each player also gets to play as one of six houses—there are more in the books, which says to me there’s an expansion coming—with each house offering a small, unique bonus or extra ability during game play.

The compact game board also has a fleet track and a space above the Institute, both of which will contribute points to your game-end total. Every player starts at 0 on the Fleet track and moves up one space whenever taking a card from Jupiter, with some cards also granting movement on the Fleet track, with a maximum value of 10 for 43 points. Each player has 10 influence cubes to place on the Institute as the game progresses, placing one when removing a card from the Institute column, again with cards granting the same power; the player with the most cubes there at game-end gets 4 points per cube, the player with the second-most gets 2 points per cube, and the player with the third-most gets 1 point per cube. (In a two-player game, you place 3 neutral cubes there and will score them, so you’re not guaranteed 2 points just for showing up.) There are also helium tokens, referring to the helium-3 isotope that the books’ hero, Darrow, is mining when the series begins; you get 3 points per helium token at game-end, but there are also cards that give you points based on your total. You get those by taking cards from Mars, and, wait for it, from deploying certain cards. And finally there’s the Sovereign token, which you get from taking cards from Luna; ending the game with that token is worth 10 points, and there are cards that give you significant bonuses if you have it as well.

The game ends when someone has passed 7 on the Fleet track, someone has placed 7 cubes on the Institute, and someone has at least 7 helium tokens, or when one player has reached two of those three thresholds. At that point, you score those three areas, give 10 points to whoever has the Sovereign token, add up your cards’ base values, and then figure out the bonuses on the cards. These vary widely and often work against each other. Certain characters want to be with their friends, but not their enemies, or even nemeses from within their own Houses. Some cards give you bonuses if a different color is absent entirely from your hand. Some give you a boost based on the Fleet track, or your helium tokens. Some cards give you a bonus if all five cards in your hand have even (or odd) base values, or values all under a certain number. It’s a puzzle with a million sides to it, and by far the best part of the game is figuring out how to maximize the interactions of your hand cards for the most points.

The deck has 112 cards, all unique, so even in a four-player game, some cards will just never come out—and in a two-player game, well, I wish you gorydamn luck. It’s hard to build too much of a strategy when you might never see half the deck; you have to stay flexible, take advantage of the cards you can see, and accept that luck plays a big part in the game—more than in any Stonemaier game I’ve played, really. At least for a game with a strong element of randomness, it plays quickly—this should never take over an hour unless you’re playing with that one friend of yours who takes ten minutes to make a move even when it’s obvious.

There’s also a competent solo mode here, as in all Stonemaier games, where you’re playing an Automa—here cleverly named Tull au Toma, mimicking the nomenclature of Gold characters in the books—that cycles through a deck of cards that instruct you to play a card from the deck to one column, take a card from one column and put it in Tull au Toma’s deck (thus permanently removing it from the game), and often to give it the column bonus as well. You score the Automa by starting with 70 points, adding points for the Fleet, helium, Institute, and Sovereign counters, and then giving the Automa points for cards in its deck that are even or odd, depending on the game setup. It’s peculiar, but produces scores that are high enough that it’s a challenge to beat them, but not impossible.

I’ve read the first book in the Red Rising series, to better prepare me to write this review, and I do think the cards are true to the characters, and designer Jamey Stegmaier has captured the interplay between characters well given the limited space for text on the cards (and some admirable self-restraint). The game doesn’t require that you’ve read the books, certainly, but I do think it requires one play before you can get enough of a feel for how the cards work with each other before you can plan effectively. That’s not a huge learning curve and the short playing time means you could play it twice in a night. It is language-dependent and definitely assumes a high reading level, so I’d say this is for the experienced gamers at the party. If you think your paradigm needs changing, check it out.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.