One of the scariest moments in Concluse is also one of the most boring. At a certain point in the Cordova Hospital, the player has to use an elevator to reach a portion of the roof. As the platform begins its laborious ascent, you peer across a black divide to a distant landscape of decaying buildings and a sinister row of—wait, are those monsters? Demons? Ghosts? Oh whew, just some white trees. Despite trekking through that section at least 10 times to finish all the puzzles, it got me every time.

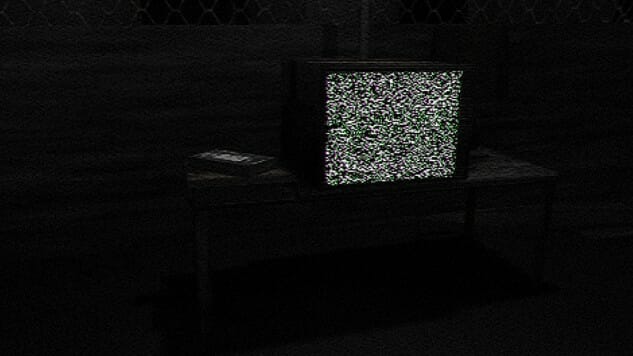

Concluse, in which a man named Michael searches for his lost wife Carolyn in the remains of a hellish New England town, has all the hallmarks of the ‘90s horror games that inspired it: a spooky hospital, a weak flashlight, and way too many damn door keys. The savepoints are infrequent, their icons a garish eyesore, and a degraded, grainy visual style suggest a “found footage” origin, a gimmick reinforced by the game’s initial premise as a “lost” PlayStation title found in an old fan’s attic. If you miss the first few Silent Hill and Resident Evil games, you’ll immediately appreciate Concluse’s vintage—but still immensely effective—sensibilities.

What is it, exactly, that makes retrograde graphics so effective in horror? A cursory glance suggests the crudeness of the graphics is a factor: not only do the jaunty, angular polygons seem distorted by comparison to modern videogame visuals, they leave some room for interpretation. The genre has long used the imagination of the audience against them; as I wrote about Faith, it’s sometimes best to provide as few details as possible and let the audience do the rest, letting them inevitably fill in the gaps with the things they find scariest. In Concluse, you know what you’re looking at is terrifying, even if (or rather, especially because) you’re just not quite sure what you’re looking at.

The limitations of the technology of 1998 (the fictional development date of Concluse) is integral to what makes the visuals seem so scary today: the disorientation, the poor lighting, the fuzzy textures always forcing you to squint in the very direction you’re so afraid of going. There’s very little music to direct or misdirect your attention, just an unsettling stillness and a creeping dread that suggests something is terribly wrong. What audio does exist is grating and unnatural, tinged with a mechanical distortion that scrapes the edges of your brain like nails on a chalkboard.

The puzzles, too, play their part; while they make sense in terms of ‘90s videogame logic, in this day and age, the giant leaps in rationale almost feel like a dream. Sure, why not pull down that painting to see if there’s something behind it? Ah, look at that, there is. And of course the player character knows that it’s an unrefined bar of metal filament! Why not? They know everything.

Like the recent Paratopic, Concluse proves that while game design is often obsessed with “pushing the envelope” mechanically and visually, abandoning certain styles and techniques the minute the technology allows us, that doesn’t mean those methods are no longer useful, or that the games they’re used in are any less valuable. Rather, they can be repurposed and used perhaps even more effectively than they were before. Everything old is new again, and in the case of Concluse, that is a very good thing.

Holly Green is the assistant editor of Paste Games and a reporter and semiprofessional photographer. She is also the author of Fry Scores: An Unofficial Guide To Video Game Grub. You can find her work at Gamasutra, Polygon, Unwinnable, and other videogame news publications.