Last week I had something of a crisis. I had absolutely nothing to write about. January is a slow month for games. So I did what any self respecting games critic does, I went over to Itch.io and threw money around like a mobster in a casino, buying everything that looked even remotely interesting. Sometimes the only way to refresh your creative and critical batteries is to take a chance on what might be pure crap.

I ended up getting about eight games and, due to their length, ran through most of them within a day. Two that stuck out for comparison were FAITH, a retro style horror game, and A Fine Mess, described as an adventure walking simulator. They share absolutely nothing in common, except that I saw them on the front page of Itch.io in the Top Sellers section. They are different in everything from premise to genre to quality and art style. But each make a claim to minimalism and achieve it to varying effect, prompting the question: when is minimalism a valid artistic decision, and when is it a cop-out?

As a narrative device, minimalism is a beautiful exercise in restraint. Providing a framework for the audience’s imagination is just as valid of a narrative choice as orchestrating every step of their experience from start to finish. There is, however, a difference between writing a story and asking the audience to write it for you. Some works of art are very good at knowing the difference. Others, not so much. What can we learn from these two games?

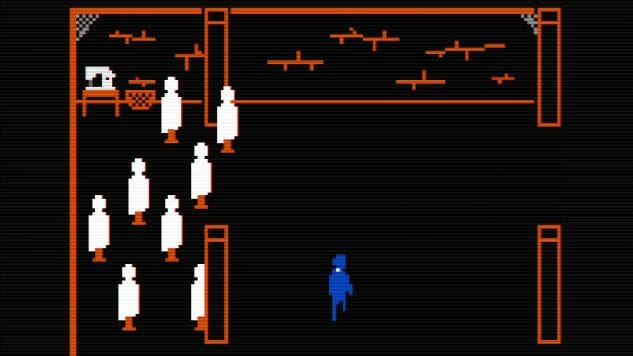

FAITH is a horror game based, visually and narratively, on the 1980s, in that the graphics are dated and the story itself is pure religious pulp, based on the “satanic panic” that peaked during the decade. Its use of minimalism is partially an homage, harkening back to the Apple II, Atari, MS-DOS and ZX Spectrum games that inspired it. Whereas those games were simple out of practicality and technological limitations, FAITH adheres to it out of sheer creative commitment: it was even developed using software from the ‘70s. Of particular note is its remarkable use of negative space to convey a foreboding sense of atmosphere. The player, upon arriving at the edge of the woods where a demonic possession previously took place, cycles almost endlessly through panel after panel of forested black, punctuated by scant landscape details holding secrets to the events of the game. The repetition and the indistinguishable features of the environment together reinforce the actual terror of walking through such a place at night: the confusion of trying to find the familiar in the dark, the growing sense of panic as everything blends together and becomes the same and you realize you are hopelessly lost. In the case of FAITH, less is more.

A Fine Mess, meanwhile, makes heavy claim to minimalism, without any clear markers of creative deliberation. The Itch.io description boldly pits it against its peers, boasting “In contrast to a conventional adventure game, there’s no hand holding or de-mystifying the story by overexplaining.” But the game doesn’t really have much to explain in the first place. Players amble along a fenced path leading to a beach as missiles soar overhead and a strange woman relaxes on the beach. There are few events or notes or moments of significance, but the ones that do exist rely on imagery and ideas that are overused and too familiar to be effective. The setting seems to be post-apocalyptic, and following a traumatic marital event between the player character and the woman on the shore, but to draw a connection between the two thematically seems to be giving the writer too much credit. The story seems less guided by an inaccessible lore that informs how the narrative is shaped, but rather, benefiting from the audience’s eagerness to fill it in for themselves. The poor production values also give away the game’s lack of deliberate qualities. The black and white visuals don’t mask the crudeness of the graphics, and serious gaps in the environment’s construction break the progression entirely. Holes in the path fencing allowed me to break through the barrier and explore the island unencumbered. Few areas outside of immediate eyesight had been embellished. A set of distant buildings were primitive and bizarrely configured, even by game design standards. I reached the water, and found that I neither drowned, nor could resurface on the shore. It’s a bare minimum effort disguised, poorly, as an artistic one. I’m almost left to wonder if this was a test project the developer was using to learn how to script events, a small demo they decided to monetize so the effort didn’t seem wasted. It would explain the lack of attention and care.

So when is narrative minimalism a cop-out? It can depend on the intent of the creator, although intent and vision don’t always perfectly translate to a finished work. The question to ask is, does the writer know more than the audience? The answer should be yes. While there are a few notable exceptions (most famously, perhaps, Hidetaka Miyazaki and Dark Souls, which arguably did have valid creative reasons for its ambiguity), for the most part, the audience should not be just as confused as the author. It should actually require more work on the part of a writer to create a minimalist narrative experience, not less.

After all, that trail of breadcrumbs is less appetizing to your audience when they’re the ones who have to bring the bread.

Holly Green is the assistant editor of Paste Games and a reporter and semiprofessional photographer. She is also the author of Fry Scores: An Unofficial Guide To Video Game Grub. You can find her work at Gamasutra, Polygon, Unwinnable, and other videogame news publications.