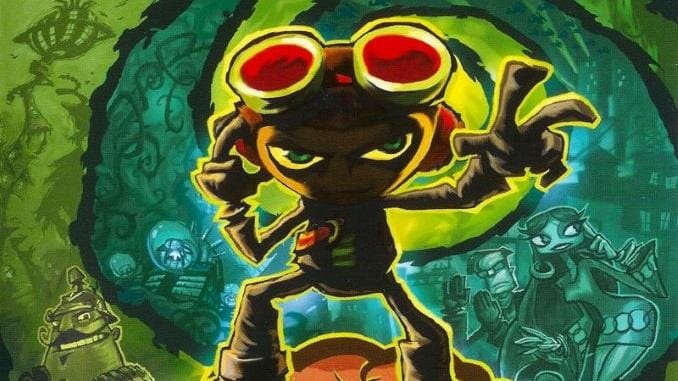

Despite Some Occasional Insensitivity, the Original Psychonauts Still Radiates Empathy

Games Features psychonauts

Despite being a serious commercial failure upon its first release, Psychonauts eventually solidified itself as a cult classic and now has a critically acclaimed sequel. Though Psychonauts 2 opens with a succinct and accurate summary, it is always worth it, to my mind, to look over what came before. What I found when I recently revisited Psychonauts shows its age. It’s clunky to play, reflective of a troubled development and a lack of institutional support. While never truly mean, its sense of humor is sometimes insensitive. However, all the markings of a cult classic are also here. While the game offers up a ton of abilities and points of interaction, all of them are useful and the game readily rewards clever play and experimentation. The writing is dense with jokes, often triggered by obscure mechanical interactions, which weaves the zany play and the cartoonish writing together. Most surprisingly, the game’s heart is firmly in the right place. It offers up an empathetic, if goofy, portrait of mental health that overcomes its more superficial shortcomings.

Psychonauts follows Raz, a young circus performer and secret psychic. He runs away from home to Whispering Rock Summer Camp, determined to become a psychic super spy, a psychonaut, before his father comes to take him home. However, sinister things are at work, and Raz quickly finds himself alone, fighting against forces that imprison and weaponize psychic minds like his.

The game proper is split between the hub world of the summer camp, and the proper levels of individual minds that Raz enters with his psychic powers. From moment to moment, Psychonauts can be a bit of a slog. Raz’s jump can feel slow to start and distances can be tough to properly judge. Generally, the platforming is easy enough that the clunkiness is not an obstacle, but in the game’s few challenging moments, it quickly becomes frustrating. While Raz’s moveset eventually becomes expansive, it’s a pain to switch between different psychic abilities.

Fortunately, the level design compensates through its inventiveness. The later levels in particular are essentially big puzzle boxes, pulling on the kind of adventure games that populate developer Double Fine’s history. The game is at its best when it is cerebral. When your brain is turning over an expansive and clever puzzle, you have less time to complain about the jumping physics. Furthermore, because each level is a section of a person’s mind, they become playable character studies. None of it is especially deep, but it is nice to see the way a person’s mind can fight against and contradict itself.

Psychonauts’ biggest downfall is still its insensitivity. For example, the game’s collectable arrowheads, a currency for buying items in the hub world, are a callous reference to colonial violence. The implication is this summer camp, which doubles as a top secret military installation, was built on top of the homes of indigenous peoples. It’s an evocation of a dark history and ongoing injustice, one that the light-hearted game is completely ill equipped to handle or really do anything with but make jokes about (or rather around). It’s not in-depth enough to warrant serious analysis, but casual fatphobia and ableism occasionally pops up. I want to be clear that none of this is malicious or even fundamental to Psychonauts’ worldview. Rather, it represents the ideological background noise of children’s media, especially when the game was released in 2005. Its occasionally insensitive humor is an unfortunately ordinary part of a lot of cartoons.

In contrast, even when Psychonauts uses outmoded language or plays on someone’s mental troubles for laughs, it always manages at least a kernel of empathy. The second half of the game takes place in a ruined asylum, as Raz helps its remaining inhabitants sort through their mental baggage. On one hand, it’s all pretty silly. One inmate suffers a delusion that he is Napoleon Boneparte, another wants to paint a portrait, but always sketches over his compositions with a bull and matador. On the other hand, all of the asylum’s inmates deal with recognizably human problems. Napoleon Bonaparte suffers from deep insecurity and feelings of inadequacy, while the painter resents an old high school flame for abandoning him for another. The system of the asylum has completely failed them; they lie in its ruins. The person who can really help them is just a little boy, with the right tools and a good heart. While Raz does completely cure them, more or less, it is still emblematic of how the system of mental health care can pathologize and imprison its subjects, rather than help them. By the end, the inmates band together and burn their former prison, a surprisingly poignant and triumphant image for such a silly game.

I’m curious to see how Psychonauts 2 recontextualizes its predecessor. That curiosity is not, as it might be for many other sequels, morbid. Psychonauts is sometimes thoughtless, but it has enough empathy that I feel confident that 16 years might push back some of its shortcomings. I still haven’t played the new game yet, but I feel excitement rather than a curious dread. In a medium filled with sequels that double down on their worst instincts, it is refreshing to feel the chance for real thoughtfulness and growth. Despite a myriad of problems, Psychonauts’ heart still beats. It’s a game that more than earns a second chance.

Grace Benfell is a queer woman, critic, and aspiring fan fiction author. She writes on her blog Grace in the Machine and can be found @grace_machine on Twitter.