Return of the Obra Dinn Starkly Renders the Violence and Greed of Colonialism

Games Features Return of the Obra Dinn

Five years ago, when Papers, Please came out and subsequently became as close to a household name as indie games can be, I was impressed by how it showed violence without showing violence. The violence of Papers, Please was more subtle, more entwined with systems of state power and suppression and separation. Papers, Please was brutish and exacting, a constant theater of alienation between the player and the harm they were inflicting on those they were processing for immigration or detention on the Arstotzkan border.

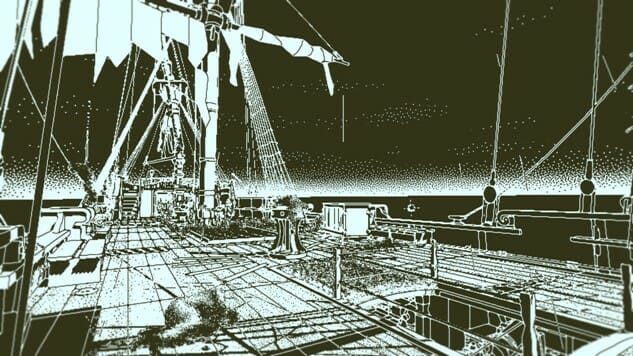

Now, in 2018, developer Lukas Pope has given us another, slightly different stage play of violence, this time more personal and less societal. Where Papers, Please hid its violence in words and regulations, Return of the Obra Dinn revels in the moment of death, the instant when the plans go wrong. It makes a ship of corpses into an elaborate math problem, each death giving you a little more information about the ship and its inhabitants.

But not all the violence is strictly interpersonal. The Obra Dinn, of course, is a ship of thieves. Not literal bandits, but the more sanctioned and regulated thievery of the East India Company. Historically, the EIC was most known for its expansionist colonialism of the Indian subcontinent, a reign of capitalist control that lasted until the mid-to-late 1800s. The East India Company was, in effect, one of the most powerful capitalist institutions in human history, and like any remnant of colonialism, its legacy still leaves scars across all the lands it touched.

In Return of the Obra Dinn, the player is tasked with investigating the deaths and various insurance claims relating to and around the ship Obra Dinn. But just as in Papers, Please the violence that you do is not in your actions—you never fire a gun, and never stab anyone, in Return. The violence of the space is left for the player to ponder after the act.

If I were to give a strong criticism of Obra Dinn, a game I very much enjoyed, I worry that it does not do quite enough to investigate the setting that it is building its fiction on. The game flirts with notions of ownership, freedom, and unjust rule, but never digs into them. Partially this is due to the game’s premise: Seeing only the moments of death of each passenger limits how much on-deck life, and thus information, can be communicated to the player.

The violence of the Obra Dinn is not just in the horrors experience on deck but in the existential monstrosity that is the voyage itself. The Obra Dinn is a merchant ship, loaded with a carriage of supernatural cargo that becomes more and more clearly a lure for monstrosities below the deep as the voyage progresses.

The tipping point, mundane as it is, was greed. Disgruntled sailors frustrated with their conditions saw a way to pass off any of their bumbling, accidental murders on the Obra Dinn’s new foreign passengers. It is clear that the passengers from Formosa (now Taiwan) were not considered welcome by the Obra Dinn’s other passengers and crew. Their words of warning went unheeded, the protective supernatural forces within the chest were broken, and the ship was doomed to a slow, if certain, destruction by beasts from below the water.

The tragedy of the Obra Dinn’s voyage was not sown in the actions aboard the Obra Dinn, but in the society that gave rise to the Obra Dinn: one where the goods and lives of the colonized were considered pillageable, something to take and take and not give heed to the words around. The tragedy of the Obra Dinn is not contained to the ship itself, but to the systems that gave rise to it.

In the game’s final moments, you are shown an insurance manifest that lists all the different passengers onboard the Obra Dinn, and, if you have so deduced them, their methods of death. These descriptions are short, to the point—“Died from a gunshot” or “Drowned” or “Speared.” They’re written in the calculating language of an insurance agent, as is wont.

But what the manifest avoids is intent. It shows deaths, and who killed whom, and where, and sometimes notes that the victim was good at their work or if they were deserters, but it says nothing about intent. Intent is messy, and hard to put into insurance-friendly forms.

In a way, this feels like a criticism that the game is making, perhaps the strongest one of all. Because the entire game experience is about unraveling this mystery—what happened to the Obra Dinn—but that’s not the goal of the game. The goal of the game is to find out how each and every passenger perished.

Return of the Obra Dinn is a game about violence cleansed of meaning. In that way, it feels like a tonal companion to Papers, Please, a game about meaning cleansed of violence. On the Obra Dinn, you will see every death intimately, and as a person, an investigator, you will naturally thread the storylines and see the ways that each death led to another. But that’s not really what insurance agents need. They just need the facts.

Those facts were the backbone of the East India Company, after all. If they could cleanse their own history of the people and the context, the profits would stand alone. And so, just like in Papers, Please, at the end of the day you are left with numbers and figures. Instead of salary, it is deaths, payouts and fines. Human lives reduced to another method for the Company to profit, even in death. Layers of greed cascading down the entire colonial system, encased in one dingy, storm-bitten boat.

Dante Douglas is a writer, poet and game developer. You can find him on Twitter at @videodante.