I initially struggled to like Sayonara Wild Hearts because of its controls. The most accessible way of playing this game, which is through the Apple Arcade, is also the worst. While its controls are purposefully simple for the sake of accessibility, it’s often difficult and playing it on a touch screen is cumbersome. If you don’t connect a controller to your phone via Bluetooth, you have to turn up the sensitivity to move properly, get used to the increased sensitivity and deal with the fact that your fingers will constantly get in the way. It’s not ideal for a game that requires constant precision. I might have given up on it, had it not been for the fact that it has one of the most surprising and comforting features I’ve witnessed in a game.

After my first few failures, I was greeted with a screen that said, “I will make your wish come true. Would you like to skip this bit?” I had three options: “yes please,” “no thank you” and “never ask me again.”

I’d honestly face this same screen myriad times because the stereotype that queer people can’t drive absolutely applies to me in the real and virtual world. And yet every time, I got the feeling I was being cared for; that the game didn’t think less of me for struggling and that there was no shame in sometimes resigning, saying “yes please” and continuing on with the rest of this electrifying experience. By the end, the frustration I had experienced resulted in a stronger appreciation for what has to be one of the most accessible games I’ve played.

Difficulty in videogames is usually seen as a link to some arbitrary kind of competence and intelligence. It’s not an uncommon belief that the “true” way to experience a game is through a specific difficulty level that lets you view your “skills” at said videogame as a badge of pride. Consequently, playing on an easy difficulty setting is viewed as an inferior experience. Videogames themselves have helped to perpetuate this notion; for instance, the easiest out of Strikers 1945’s seven difficulty settings is offensively titled “monkey.” Duke Nukem: Time to Kill’s easiest difficulty is named “wussy,” Viewtiful Joe’s is named “kids,” and Crusader: No Remorse’s is the rather presumptive “mama’s boy.” It’s not hard to see why we’ve formed a culture where every time a FromSoftware game is released, there’s discourse about difficulty that often delves into exclusionist territory.

This notion is exacerbated when you’re a woman or simply not a straight cis man. It’s often assumed that you can only play on the easiest difficulty, or that you pick a character or class that’s “easy to play” in games like Overwatch because you’re not good enough for the ones that require high skill. Whether you do or don’t isn’t what matters; it’s the notion that your skills are at all tied to the difficulty setting you choose to play. That your skills (or lack thereof) are why you pick that setting rather than the plethora of other possible reasons, like having a job, a family, or simply an unwillingness to find fun in wrestling with a videogame in order to see the full story. It’s gotten better with games like Celeste—which is known for its extreme difficulty—implementing an Assist mode to be more accessible, but it’s an issue that will likely always be discussed due to its nuances. For some games, the challenge is a defining factor to their appeal and identity.

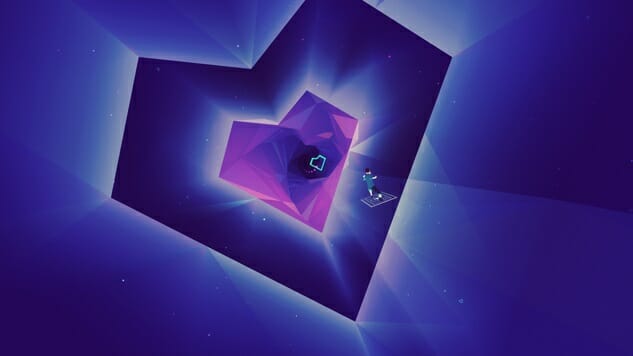

Sayonara Wild Hearts’ utter confidence is thus all the more admirable. With its intense fuschias and magentas, magical girl-esque transformations and aesthetics, pretty and girly pop music, and queer subtext, its identity is a proud antithesis to toxic misconceptions regarding videogames, difficulty, skill, and gender. It’s not shy about being a fairly difficult game—it’s hard enough to maneuver your way around high-speed roads while shooting arrows, collecting hearts, and throwing kicks and punches, but its instantly captivating soundtrack makes it all the more challenging to focus entirely on the road. (I promise this is not an issue during the rare occasion that I drive in real life). Even though it lasts less than two hours, it constantly shifts and evolves, experimenting with a wide variety of mechanics and styles while never forsaking its own stylish elements that make it unique.

Perhaps one of the few things it doesn’t forsake is its core of love and empathy, and I’m glad that it extends those things to the player. It has the confidence to acknowledge its challenges and then ultimately refuse to deem them as integral to your enjoyment of it. Its controls are simplified to make a challenging experience easier, and on top of that it asks you for your consent to skip past a particularly difficult section without any judgment—without anything but acceptance. I enjoyed working to overcome an obstacle, sometimes realizing it was too difficult, and knowing I could feel at peace when I pressed “yes please.”

Sayonara Wild Hearts begins with a lonely broken-hearted girl and ends with a celebration of love and empathy as she kisses all her foes away. It’s ultimately about love—letting go of love, loving yourself, and displaying love for others. But it’s also about sharing some of that love with you, the player, too. The game is gentle enough to constantly push me to do my best but accepts that sometimes my best in that moment isn’t enough—and that this is okay. That I’m not a failure for it, and that it doesn’t mean I can’t overcome another challenge with different rules and tests; that I, too, deserve to enjoy the good things in life despite what others may believe. And maybe that’s a large part of what love is all about.

Natalie Flores is a freelance writer who loves to talk about games, K-pop and too many other things.