“Fake News” Isn’t New, and the New “Fake News” Isn’t as Influential as We Think

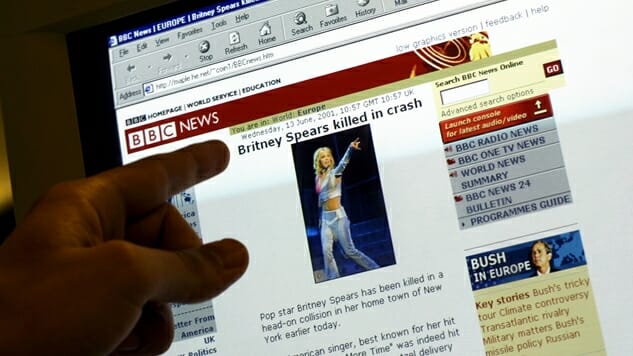

Photo by Sion Touhig/Getty Media Features Fake News!

Margaret Sullivan of the The Washington Post wrote a column last night detailing the news consumption of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. Barack Obama beat John McCain there by eight and a half points in 2008, and won by five points over Mitt Romney in 2012. Registered Democratic voters outnumber their Republican counterparts by three to two in Luzerne. Despite all these Democratic advantages in a county located just south of Joe Biden’s hometown of Scranton, Donald Trump obliterated Hillary Clinton by 20 points there this past November. Luzerne is ground-zero for understanding how America’s changing demographics and economics gave us President Donald Trump, yet in the aftermath of the election, these counties have been dismissed as areas filled with uneducated rubes who will believe anything that confirms their biases.

The wild story of Macedonian teenagers flooding the internet with made-up articles, making tens of thousands of dollars per month has been told so many times that it has taken up a larger space in our collective consciousness than its measurable impact deserves. Given the post-election hysteria, one would think that these sites decided the outcome. On November 16th of last year, Stephen Colbert’s monologue included a bit about these sites, saying:

“As of today, Facebook will restrict these fake news sites. Now they’re going to do it. Also, while we’re at it, let me just close these barn doors so those stupid cows can’t get back in. Enjoy your fields, stupid fucking cows.”

As of this writing, that video has over 1.8 million views. An assumption has taken root which has not proven to be true—yet amongst many liberals, it seems to be common knowledge that “fake news” is the central explanation as to why counties like Luzerne could so overwhelmingly vote for Donald Trump. However, when The Washington Post interviewed people from Luzerne, they found that their media consumption does not line up with this narrative. Margaret Sullivan wrote:

And you’ll hear, over and over, that what matters most are the news sources that are closest to home. Trump may have effectively demonized the national media. But in a dozen interviews here last week, Luzerne residents indicated their satisfaction with their main news sources: WNEP Channel 16, the ABC affiliate in Wilkes-Barre; and the two competing Wilkes-Barre daily papers: the Citizens’ Voice (which endorsed Clinton) and the Times Leader (which made no endorsement).

The hysteria surrounding Facebook’s influence over the election stems from the Pew report which showed that 44% of Americans get their news from Facebook. Combine that figure with the impression that Macedonian teenagers are producing the majority of that content, and the result is a skewed perception of the pervasiveness of “fake news.” However, given that every single outlet in the world has a Facebook page, that’s about as descriptive as saying in the early 20th century that you got your news from “a newspaper.”

Granted, in the months leading up to the election, this flood of nonsense likely benefited Trump more than Clinton, as cited in a study by Stanford University:

Of the known false news stories that appeared in the three months before the election, those favoring Trump were shared a total of 30 million times on Facebook, while those favoring Clinton were shared eight million times

However, that same study also found that “fake news” is not very convincing.

We estimate that in order for fake news to have changed the election result, the average fake story would need to have f ~= 0.0073, making it about as persuasive as 36 television campaign ads.

In fact, it demonstrated that the three most widely believed “fake news” stories in the election were ones favorable to Hillary Clinton (note: the sample was limited to stories debunked on Snopes. The blue bar in this chart is the percentage of people who believed the story, and red are those who “weren’t sure”). Snopes’ managing editor, Brooke Binkowski, told The Atlantic that she had seen an uptick in “fake news” aimed at liberals post-election.

A lot of dubious news, a lot of wishful thinking-type stuff. It’s not as filthy as the stuff I saw that was purportedly coming from the right—I don’t think a lot of it was actually coming from the right, I think it was coming from outside sources, like Macedonian teenagers, for example—but there has been more from the left. It’s more wish-fulfillment stuff. “Trump About to be Arrested!” Well, yeah, when’s that gonna happen? And we know it’s coming from the left because I know it’s coming from known players. Bill Palmer used to run the Daily News Bin, and it was basically a pro-Hillary Clinton “news site.” It was out there to counter misinformation. Which, okay, fair enough. But then he started to reinvent it as a news site, more and more, and he changed the name to the Palmer Report. The stuff that he puts out there, it’s nominally true. When you click on it, it’s some innocuous story [with an outlandish headline]. That is very harmful, I think.

I’m putting “fake news” in quotes because it is a term that has utterly no meaning. At first, it simply referenced these Macedonian sites and their ilk, but now it has been extrapolated to oppose anything considered to be the “truth.” I put “truth” in quotes because it is an evolving concept which is losing its meaning more and more each day (note: of course there are clearly objective truths like gravity, but “truth” in this instance refers to the pursuit in political journalism). Mankind has gotten a lot wrong in our brief history on this planet, and the “truth” largely depends on the era you live in.

Journalism is typically seen as being something like target practice—where the objective is obvious and it is incumbent upon the writer to reach the destination—when in fact, it’s more similar to chiseling something out of stone. It is a messy, arduous process which demands patience and delicate hands. Even though there is an overall goal in mind, the journey will take you down various and unexpected roads. Perception is very much reality, yet our concept of the “truth” is a static one, and not the ever-shifting target that history has proven it to be.

In order to ascertain the “truth,” sourcing is paramount. However, this is the central issue: what sources can be trusted? This “fake news” debate infers that we are losing reliable outlets who produce empirically factual information; however, one look at America’s history demonstrates the folly of this belief—as journalist Marcy Wheeler (also known as “emptywheel”), elucidated on her blog:

I’ve got news (heh) for you America. What we call “news” is one temporally and geographically contingent genre of what gets packaged as “news.” Much of the world doesn’t produce the kind of news we do, and for good parts of our own history, we didn’t either. Objectivity was invented as a marketing ploy. It is true that during a period of elite consensus, news that we treated as objective succeeded in creating a unifying national narrative of what most white people believed to be true, and that narrative was tremendously valuable to ensure the working of our democracy. But even there, “objectivity” had a way of enforcing centrism. It excluded most women and people of color and often excluded working class people. It excluded the “truth” of what the US did overseas. It thrived in a world of limited broadcast news outlets. In that sense, the golden age of objective news depended on a great deal of limits to the marketplace of ideas, largely chosen by the gatekeeping function of white male elitism.

Brett Baier, who is one of the few people at Fox News who can be classified as a journalist, reported perhaps the most devastating “fake news” story of the election: that Hillary Clinton was about to be indicted by the FBI. He issued a retraction and apologized, but the damage was done. People mainly remember whatever was reported first, as every single misguided joke about the Duke men’s lacrosse team still demonstrates to this day.

Judith Miller of The New York Times produced countless stories which helped lead us into Iraq, echoing the mistakes newspapers made in the 1960s and 1970s with the Vietnam War. Simply repeating what “officials” or “sources” say without independent verification isn’t news, it’s rumor-mongering. However, when an outlet with the validity of the Times prints something false, it’s not characterized as “fake news,” despite the fact that it is infinitely more damaging than these “fake news” sites due to the validity of the NYT brand. Because it has only been used to definite less legitimate institutions, Donald Trump is able to use this cudgel to bring any story he doesn’t like down to this newly-invented level.

Any negative polls are fake news, just like the CNN, ABC, NBC polls in the election. Sorry, people want border security and extreme vetting.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 6, 2017

Capitalism further complicates matters. Because the business model of journalism is based on exposure, truth is secondary to interest as far as everyone’s bottom line is concerned. When I sit down every morning to figure out what to write, I know that I have to select a subject that people will actually click on—otherwise I may as well walk outside and scream my column into the void. If you were paying a subscription to Paste, my need to find “clicky” stories would be lessened, as you have already demonstrated your interest by giving us your money. At its most extreme, the intersection of capitalism and journalism produces networks like Fox News and MSNBC, who spend the majority of their days confirming their viewers biases—or the even more severe outright propaganda outlets like Brietbart and Infowars. At a more reasonable end, it produces sites like Buzzfeed who largely do good journalism, but they are mainly funded by the ads on their “clicky” stories.

Advertising has always affected what goes on the news—as no one wants their product placed next to a depressing story that will take people out of the mood to spend money, but the internet has taken a somewhat manageable problem to DEFCON 1. Given the right formatting, everyone’s words look the same next to each other, and this flattens the playing field, creating an expansive competition for clicks. If you’re a fervent Trump supporter who takes his word as gospel, why go to the New York Times to read about the National Security Council in turmoil and how that’s problematic, when Infowars will tell you that it’s a good thing that Donald Trump is ridding America of evil people who conduct alleged false flag operations like Sandy Hook?

Journalism is portrayed as this opaque institution with unreachable gatekeepers because a bunch of old, rich, white men wanted it to look that way in order to control the narrative to benefit their agenda. This opened up a lane for outlets like Infowars, who are able to define their legitimacy solely through the illegitimacy of the mainstream media. Once the internet blasted open the floodgates and allowed people like me to utilize many of the same sources The New York Times has access to, it dramatically changed the game. Not only have we not caught up to this new reality, but we have yet to understand the old one. Mack Hayden nailed the issue at the heart of all this in a piece for Paste a few weeks back:

“Fake News” is a symptom, not a disease in and of itself, and this disease affects everyone. The ailment is one of resting on our laurels, of considering contestable information to be settled once and for all because we like it. This cancer of Confirmation Bias erodes our individual objectivity as information consumers. The way to cure this larger problem isn’t through getting rid of the bad information. That’s giving a man a fish. Teaching a man to fish, in this situation, means equipping everyone with a toolset of critical thinking that’ll still bring people to different conclusions, but on the basis of firmer rationale.

Journalism is an imperfect process that mankind has yet to master. Stop obsessing over what is “fake” and what is “news” and start focusing on what is verifiable. I’m held to a higher standard because it is my job, but anyone can practice the basic tenet of journalism: find two independent sources which confirm the same story. If the piece you’re reading does not provide specific sourcing for its claims (ie: at least a name or a link), then you should question their narrative. Frankly, the basics aren’t much more difficult than that—but classifying stories as either “fake” or as “news” completely misses the point of what we’re doing here. There are no objective truths in political journalism, only verifiable ones.

Jacob Weindling is Paste’s business and media editor, as well as a staff writer for politics. Follow him on Twitter at @Jakeweindling.