Some of the best horror movies of the year could be argued off the following list on a technicality. One of the best horror movies of the year is pretty much not, more about the communal joy of horror filmmaking than a rigorous, rule-abiding pick. As a good, clean man once said, “It don’t matter. None of this matters.”

If you’re looking for a wrap-up of the genre in 2019, we can’t do better than to simply direct your attention to Jim Vorel’s final entry in his massive survey of the past 100 years in horror.

Here are our picks for the 10 best horror movies of the year:

10. One Cut of the Dead

10. One Cut of the Dead

Director: Shinichirou Ueda

Director Higurashi (Takayuki Hamatsu), beleaguered protagonist of Shinichirou Ueda’s box office indie smash One Cut of the Dead, has two modes: “On” and “in dire need of an ‘off’ button.” Even at his most sedate, Higurashi hums with the unharnessed energy of a pent-up greyhound, always at the ready for a race around the track but conditioned to patiently wait until the signal is given. Once it is, he’s a sight to behold, a man unleashed, screaming like a maniac christened as dictator, vaulting around sets with such vigor and dexterity to put the world’s parkour champions to shame. Ueda first introduces Higurashi as a despotic indie filmmaker howling at his weeping star, Chinatsu (Yuzuki Akiyama), then 37 minutes later reveals the man to be a docile, much too obliging videographer who chiefly works on weddings and karaoke clips. It’s a glorious, bonkers 37 minutes, too, presented as a zombie movie shoot gone wrong. Higurashi and his cast—Chinatsu, former actress (and Higurashi’s wife) Nao (Harumi Shuhama), and pain in the ass leading man Ko (Kazuaki Nagaya)—and crew have set up shop at a decrepit, isolated warehouse that also stores a coterie of shambling undead. As they’re besieged by ghouls, Higurashi, yet to find a take that he actually likes, keeps on filming through the carnage. Of course it’s all a film-within-a-film. Once One Cut of the Dead shifts gears from a zombie movie to a backstage inside baseball comedy, the initially cold atmosphere Ueda establishes warms up. The amateur terror of Higurashi’s guerilla filmmaking gives way to winning charms as the audience gets to see who he really is, what this project means to him and just how damn hard it is to make a movie in a single take. It’s chaos, but it’s controlled chaos (even if only just), and in the chaos there’s absolute joy. One Cut of the Dead ends with smiles, pride, reconciliations and the accomplished sense of having achieved the impossible. If that’s not a ringing endorsement of collaborative art’s benefits, then what is? Maybe Ueda’s film is an odd messenger for delivering such high sentiment, but it’s the messenger we have, and we should embrace it. —Andy Crump / Full Review

9. Climax

9. Climax

Director: Gaspar Noé

Gaspar Noé has been so openly confrontational and provocative for so long that it’s easy to forget just how powerful a filmmaker he can be. He is deliberately repulsive, sometimes to the detriment of his own films; I don’t care how structurally inventive Irreversible is, I am never, ever sitting through that goddamned movie again. But there is an undeniable hypnotic fervor to his movies, from the sordid (but also sort of lovely) kink of Love to the elliptical madness of Enter the Void. The immediate thrill of Climax, Noé’s newest and unquestionably best film, is how, for the first time, you see him letting go a little bit, releasing some of his notorious control, letting his characters breathe a little bit—to be themselves. It opens with home-camera footage—the film takes place in 1996of a series of dancers, readying for a troupe tour of the United States, answering questions about their hopes and dreams, their desires, their fears, their basic motivations. It’s a slick, kind of cheap, but still incredibly effective way for Noé to give us just enough information about these dancers that we feel for them when they go through whatever Noé is about to put them through. (And you know he’s going to put them through something.) But it’s what comes next that’s most exciting: during rehearsal, a glorious dance routine featuring the entire crew, both meticulously choreographed and thrillingly improvised, expressing themselves the best way they know how. Noé’s camera swirls around in one long take, and the effect is breathtaking: It is as alive and electric as anything Noé’s ever done. Now you’re really invested in this crew…which, as Noé’s counting on, was your first mistake. It turns out, someone has spiked the sangria for the post-rehearsal part with LSD, and, apparently, a lot of it. Even if he puts all these people through the ringer—and oh, does he!—there is inspiration here: For the first time, it feels like the pain he’s putting everybody through is something he feels, too. It’s turned him into less of a Lars Von Trier geek show. Not to say that the ending doesn’t pack a wallop regardless. Noé, for all his newfound pseudo-humanism, isn’t going to send you home wanting for misery. But there is…well, not hope, exactly, but call it catharsis. He’s as uncompromising, and as resolutely himself, as ever. It’s just that there might be a little more shading and warmth inside Noé than maybe even he himself realized. Don’t misinterpret, though: This is Gaspar Noé Warmth, not normal human being warmth. Rest assured, his world remains no place for children. —Will Leitch / Full Review

8. Daniel Isn’t Real

8. Daniel Isn’t Real

Director: Adam Egypt Mortimer

Everyone has their demons: Maybe they grew up neglected, or trapped between warring parents—or maybe they saw things they shouldn’t have before they had the tools to process them. Some of these people manage to grow up well-adjusted in spite of their trauma. Others grow up keeping those demons close to their heart. Mercifully, none of this is literal, but what if, Adam Egypt Mortimer’s Daniel Isn’t Real asks, those demons look like the dashingly handsome spawn of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Maria Shriver? Mortimer weaponizes Patrick Schwarzenegger’s pedigree and good looks, turning him into both the best imaginary friend a loner like Luke (Miles Robbins, also the son of Hollywood royalty: Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon) could ever hope to have, and the perfect catalyst for Luke’s transformation into an oily pickup artist at best and a true-to-form monster at worst. The subtext is on the surface—it’s a film about toxic masculinity—but Mortimer and his cast (which includes Sasha Lane, who takes the thankless role of “damsel trapped between hero and villain” and turns it into a performance of substance) shatter that surface, digging deep, then deeper, and then deeper still into the guts of that grossly overused pop psych phrase. What they find is thought-provoking insight into modern masculine identity. What they create with those insights is terrifying, a tactile smorgasbord of frights that wears its influences on its sleeve. (Would you guess that Mortimer loves Ridley Scott and Takashi Miike?) Those influences metastasize into one of 2019’s most memorable and original horror films. —Andy Crump

7. Tigers Are Not Afraid

7. Tigers Are Not Afraid

Director: Issa López

It’s possible, even probable, that a portion of Tigers Are Not Afraid’s audience will receive the film as a parable about the current humanitarian crisis unfolding along the U.S.-Mexico border, a clarion call for compassion and decisive legislation to put an end to the suffering inflicted on innocent families fleeing mortal peril and economic repression. Such is the myth of America’s legacy. But Issa López made Tigers Are Not Afraid years ago, before the administration in power escalated the United States’ already appalling immigration policies into full-on decimation. This is not a cry for action. It’s a snapshot of Mexico’s recent history that bleeds into its present day. As such, Tigers Are Not Afraid molds the sickening consequences of cartel violence on Mexico’s children to fit the shape of folkloric narrative. It’s a fairy tale, and a horror film, though the two tend to go hand-in-hand: Fairy tales point us to the darkness that exists on society’s periphery—or, in this case, occupies society’s center. The world of Tigers Are Not Afraid is made of crumbling walls and whispers, a land of ghosts where children are acclimated to ducking for cover under their desks when bullets interrupt class time. (Another thread to tempt viewers toward forced topical readings.) All the world is horror even before López starts ushering ghosts into the fray.

Estrella (Paola Lara) is one orphan among many in the unnamed border town López has chosen as the film’s location. When she’s given three wishes by her teacher, she immediately asks for her mother to return. Her mother does—but the conditions of her return are fuzzy, so mom resurrects as a hoarse, desiccated revenant. On the opposite end of the spectrum is Shine (Juan Ramón López), also an orphan, but one devoted to keeping his fellow orphaned boys safe on the streets as they outmaneuver cartel thugs and perhaps hope to find justice against them. Estrella and Shine share the screen as sun and moon share the sky, casting the film with light and darkness amidst graffiti-streaked buildings, the threat of death lurking in alleyways and on street corners. With Tigers Are Not Afraid, López threads the needle through tragedy and hope. This is at once a grim movie, an optimistic movie and a redemptive movie. It’s a welcome reminder that fairy tales and folklore are an essential part of our culture, too. At the most inhuman times, they lay down a path back to humanity. —Andy Crump

6. Hagazussa: A Heathen’s Curse

6. Hagazussa: A Heathen’s Curse

Director: Lukas Feigelfeld

Content warning for people with misgivings about cannibalism, vomit, organ splatter, maggoty mushrooms, sexual assault and infinitely worse: Hagazussa provides a minefield of triggers. It’s gross. It’s also stunning, a hypnotic recreation of its time and its place: 15th century Europe, a land cast into the dark ages long before the advent of the age of reason. In between unsettling and barefaced displays of noxious human ills and pseudo hallucinatory insanity rest still frames so gorgeous they belong in their own art gallery tableau. Snapshots of Austria’s countryside megacosm center on Albrun (Alexsandra Cwen), a woman orphaned as a girl and still alone as an adult, who spends a majority of her time trudging through and taking respite in the forests of her homeland. But Hagazussa’s idyllic appeal belies evil lurking in its frames, stalking Albrun like a basilisk, turning the woods she inhabits to stone. Albrun is marked from birth, doomed to alienation from and othering by her fellow man. As a child, depicted in the film’s opening chapter by Celina Peter, she and her mother, Martha (Claudia Martini), are harassed in dead of night by men disguised in fearsome horn-headed costumes, as concealing as they are intimidating. They’re infernally convinced Martha’s a witch. An hour and change later, the audience is given reason to wonder if they were right. To young Albrun, their incursions qualify as nightmares worse than those chronicled in fables. In the present day narrative, the prejudice of her youth follows her. She’s harassed by snotty village boys, then spared their taunts by a seemingly benevolent woman, Swinda (Tanja Petrovsky), then manipulated into serving Swinda’s own perverse ends. If Albrun isn’t a witch, society does a bang-up job giving her incentive to reconsider the calling. Hagazussa is further distinguished through a patina derived from David Lynch and Panos Cosmatos—slow, deliberate, perpetually unsettling. The film takes its time, but it drags the viewer along the way toward a mind-shattering oblivion. Are Albrun’s visions real, or figments of her imagination? Is witchery truly afoot, or is she just losing her marbles at the business end of ignorant mob persecution? The last of these is the only question with an emphatic “yes” answer, though the idea that the real monster here is Woman is pedantic bordering on boorish. Movies like this function because the monster exists, not simply because people historically treat outsiders like stray dogs at best, vermin at worst. —Andy Crump / Full Review

5. Knife + Heart

5. Knife + Heart

Director: Yann Gonzalez

Yann Gonzalez’s gleeful genre mashup Knife Heart is a queer provocation, a delirious journey through celluloid mirrors, daring to assert that pornography is as ripe for personal catharsis as any other art form. In the wake of a breakup with her editor Loïs (Kate Moran) and the murder of one of her actors, gay porn producer Anne (Vanessa Paradis) sets to make her masterpiece, one saturated with her rage and heartbreak. She sends a clear message to her lover etched into a reel of dailies, one of her performers’ head back in ecstasy as if in Warhol’s Blow Job: “You have killed me.” As her cast and crew are killed off one by one, Anne pushes on, driven to put herself in her work, literally and figuratively, the spectre of doom for her shared community growing ever closer. Gonzalez’s film pulsates with erotic verve and a beating broken heart, as if giving yourself up to cinema is the only thing that can keep you alive. When the lights go down and the wind screams through the room, it’s as if Knife Heart, and by extension all film, is the last queer heaven left. —Kyle Turner

4. Midsommar

4. Midsommar

Director: Ari Aster

Christian (Jack Reynor) cannot give Dani (Florence Pugh) the emotional ballast she needs to survive. This was probably the case even before the family tragedy that occurs in Midsommar’s literal cold open, in which flurries of snow limn the dissolution of Dani’s family. We’re dropped into her trauma, introduced to her only through her trauma and her need for support she can’t get. This is all we know about her: She is traumatized, and her boyfriend is barely decent enough to hold her, to stay with her because of a begrudging obligation to her fragile psyche. His long, deep sighs when they talk on the phone mirror the moaning, retching gasps Pugh so often returns to in panic and pain. Her performance is visceral. Midsommar is visceral. There is viscera, just, everywhere. As in his debut, Hereditary, writer-director Ari Aster casts Midsommar as a conflagration of grief—as in Hereditary, people burst into flames in Midsommar’s climactic moments—and no ounce of nuance will keep his characters from gasping, choking and hollering all the way to their bleakly inevitable ends. Moreso than in Hereditary, what one assumes will happen to our American 20-somethings does happen, prescribed both by decades of horror movie precedent and by the exigencies of Aster’s ideas about how human beings process tragedy. Aster births his worlds in pain and loss; chances are it’ll only get worse.

One gets the sense watching Midsommar that Aster’s got everything assembled rigorously, that he’s the kind of guy who can’t let anything go—from the meticulously thought-out belief system and ritual behind his fictional rural community, to the composition of each and every shot. Aster and his DP Pawel Pogorzelski find the soft menace inherent to their often beautiful setting, unafraid of just how ghastly and unnatural such brightly colored flora can appear—especially when melting or dilating, breathing to match Dani’s huffs and the creaking, wailing goth-folk of The Haxan Cloak. Among Midsommar’s most unsettling pleasures are its subtle digital effects, warping its reality ever so slightly (the pulsing of wood grain, the fish-eye lensing of a grinning person’s eye sockets) so that once noticed, you’ll want it to stop. Like a particularly bad trip, the film bristles with the subcutaneous need to escape, with the dread that one is trapped. In this community in the middle of nowhere, in this strange culture, in this life, in your body and its existential pain: Aster imprisons us so that when the release comes, it’s as if one’s insides are emptying cataclysmically. In the moment, it’s an assault. It’s astounding. —Dom Sinacola / Full Review

3. The Lighthouse

3. The Lighthouse

Director: Robert Eggers

Sometimes a film is so bizarre, so elegantly shot and masterfully performed, that despite its helter-skelter pace and muddled messaging I can’t help but fall in love with it. So it was with the latest film by Robert Eggers. An exceptional, frightening duet between Robert Pattinson and Willam Dafoe, The Lighthouse sees two sailors push one another to the brink of absolute madness, threatening to take the audience with them. Fresh off the sea, Thomas Wake (Dafoe) and Ephraim Winslow (Pattinson) arrive at the isolated locale and immediately get to work cleaning, maintaining and fixing up their new home. Everything comes in twos: two cups, two plates, two bowls, two beds. The pair work on the same schedule every day, only deviating when Thomas decides something different needs Ephraim’s attention. Like newlyweds sharing meals across from one another each morning and every evening, the men begin to develop a relationship.

It takes a long time for either of the men to speak. They’re both accustomed to working long days in relative silence. They may not possess the inner peace of a Zen monk, but their thought processes are singular and focused. Only the lighthouse and getting back to the mainland matters. Eggers uses the sound of the wind and the ocean to create a soundscape of harsh conditions and natural quarantine. The first words spoken invoke a well-worn prayer, not for a happy life, or a fast workday, but to stave off death. A visceral ride, The Lighthouse explores man’s relationship to the sea, specifically through the lens of backbreaking labor. Thomas and Ephraim’s relationship is like a Rorschach test. At times they are manager and worker, partners, enemies, father and son, competitors, master and pet, and victim and abuser. In many ways Eggers’ latest reminds of Last Tango in Paris, which explored a similar unhealthy relationship dynamic. Just as captivating, The Lighthouse shines. —Joelle Monique / Full Review

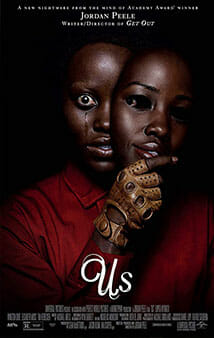

2. Us

2. Us

Year: 2019

Director: Jordan Peele

Us clarifies what Get Out implies. Even after only two films, Jordan Peele’s filmmaking seems preconfigured for precision, the Hitchcock comparisons just sitting there, waiting to be shoved between commas, while Peele openly speaks and acts in allusions. Us, like Get Out before it but moreso, wastes nothing: time, film stock, the equally precise capabilities of his actors and crew, real estate in the frame, chance for a gag. If his films are the sum of their influences, that means he’s a smart filmmaker with a lot of ideas, someone who knows how to hone down those ideas into stories that never bloat, though he’s unafraid to confound his audience with exposition or take easy shots—like the film’s final twist—that swell and grow in the mind with meaning the longer one tries to insist, if one were inclined to do so, that what Peele’s doing is easy at all. A family comedy studded with dread, then a home invasion thriller, then a head-on sci-fi horror flick, Us quickly acquaints us with the Wilson family: calming matriarch Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o), gregarious dad Gabe (Winston Duke), daughter wise beyond her years Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and adorable epitome of the innocent younger brother, Jason (Evan Alex). Though far from shallow, the characters take on archetypal signifiers, whether it’s Zora’s penchant for running or that Gabe’s a big guy whose bulk betrays a softer heart, Peele never spoonfeeding cheap characterizations but just getting us on his wavelength with maximum efficiency. Us isn’t explicitly about race, but it is about humanity’s inherent knack for Othering, for boxing people into narrow perspectives and then holding them responsible for everyone vaguely falling within a Venn diagram.

Regardless of how sufficiently we’re able to parse what’s actually going on (and one’s inclined to see the film more than once to get a grip) the images remain, stark and hilarious and horrifying: a child’s burned face, a misfired flare gun, a cult-like spectacle of inhuman devotion, a Tim Heidecker bent over maniacally, walking as if he’s balanced on a thorax, his soul as good as creased. Divorced from context, these moments still speak of absurdity—of witty one-liners paired with mind-boggling horror—of a future in which we’ve so alienated ourselves from ourselves that we’re bound to cut that tether that keeps us together, sooner or later, and completely unravel. We are our undoing. So let the Hitchcock comparisons come. Peele deserves them well enough. Best not to think about it too hard, to not ruin a good thing, to demand that Us be anything more than sublimely entertaining and wonderfully thoughtful, endlessly disturbing genre filmmaking. —Dom Sinacola / Full Review

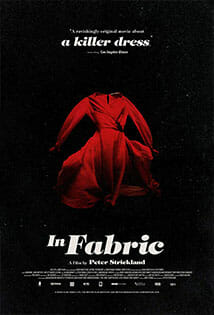

1. In Fabric

1. In Fabric

Director: Peter Strickland

Peter Strickland is a cinematic aesthete; an artist who is both beguiled by and displays a mastery over the slightest and most ephemeral elements of production design, visuals, texture and sound in his films. In 2012’s Berberian Sound Studio, he first applied this degree of hyper-attention toward the psychological horror genre, setting his story within the world of film industry foley itself to provoke audience reflection on sound and the nature of reality. In 2019’s In Fabric, meanwhile, he once again returns to core influences that range from Italian giallo to 1970s European erotic thrillers, but suffuses them with a gauzy style that is all his own. Into this topsy-turvy world, Strickland brings two central characters who seem to have originated from outside it, “regular” people who are frequently just as confounded as we would be by the bizarre behavior of those around them. One, single mother Sheila (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), just wants to get back out there into the dating game, only to find herself as seemingly the only sane individual in a world full of totally irrational people. Her supervisors chide her about utterly insignificant infractions like her style of waving hello, and probe deeply into her personal life, including even the content of her dreams. She reacts with flustered confusion that is perfectly natural, but still can’t turn down their bizarre requests, even as she begins to suspect that her beautiful new red dress (in a tiny catalog detail, we see its color listed as “artery”) contains a malignant presence. Perhaps she should have been more unnerved when buying it from the witchy, sinister store clerk Miss Luckmoore (Fatma Mohamed, spouting some of the craziest dialog of the year), a character who looks like she leapt straight out of the unconscious mind of Dario Argento.

Strickland conveys this story with the dreamy excesses and mood projection of Nicolas Winding Refn in the likes of Valhalla Rising, but somehow manages to dive even deeper into its aural aspects than he did in Berberian Sound Studio. There’s a message buried in here as well, a commentary on consumerism that presents shopping and browsing for “life-improving” consumer goods as something like an ecclesiastical (or pagan, more likely) religious experience, but it’s the all-encompassing aura of In Fabric that makes it stick in the mind. It perfectly captures universal experiences that have been given supernatural portent. There’s the pain of shattered expectations on a terrible first date. The rote sexual congress of a long-time couple, long since reduced to a series of mechanical motions. The disorienting quality that a disturbing dream has on coloring a person’s experiences in the waking world. Strickland presents it all, and more, in 2019’s most deeply effective horror film. —Jim Vorel / Full Review