Each month, the Paste staff brings you a look at the best new selections from The Criterion Collection. Much beloved by casual fans and cinephiles alike, The Criterion Collection has for over three decades presented special editions of important classic and contemporary films. You can explore the complete collection here. In the meantime, here are our top picks for the month of May:

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

Director: Chantal Akerman

Year: 1975

The particulars of Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles are human, but its inner workings are mechanical. You can practically hear the sound of gears and springs beneath its muted, unchanging exterior, its title character, a single mother who spends her days cooking, cleaning, mothering, and fucking, an automaton of regimented predictability. Therein lies the extent of the film, the masterwork of the great Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman; it’s the definition of a slow-burn, a methodical representation of real life packed with clues to unveil the slow unraveling of Jeanne over the course of three days in her life. Akerman stays with her subject from the crack of dawn to the evening’s close, showing, in unsparing detail, the activities that comprise each 24-hour period of Jeanne’s existence: She goes to the post office, she goes to the grocery store, she briefly attends her neighbor’s baby and entertains small-talk, she lays with her male clients, her only source of income, and then she spends quality time with her mollusk of a son. Title cards announce the end of one day and the start of another, and in between each, we see the cracks in Jeanne’s routine, at least if we’re keen enough observers.

What is Akerman’s ultimate message? Is Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles a meticulous cry of outrage directed at a social system that fails to support people in need of aid? Is it an all-purpose tut-tutting of modernity’s tendency of treating human beings like cogs in a wheel? Or is it just a chilling portrait of how even the slightest change in a person’s habits can throw their entire life off course? (Maybe it’s a culinary warning that we should strive to never overcook our potatoes.) Make of it what you will. The film is pliable enough to invite as much interpretation as you feel like mustering. It’s also a one of a kind experience in cinema and a badge of viewing honor: 201 minutes of realism is a lot, but Akerman makes each mesmerizing and eminently engrossing. —Andy Crump

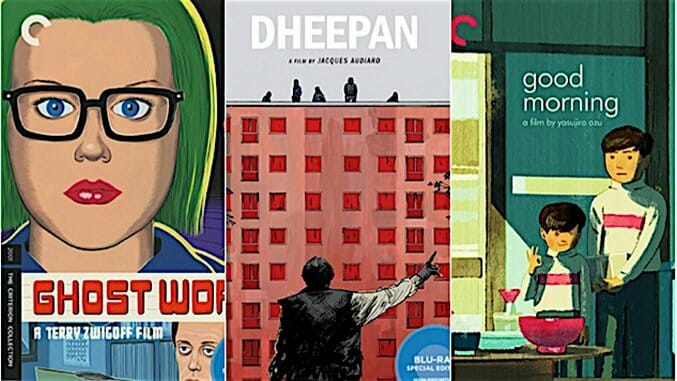

Dheepan

Dheepan

Director: Jacques Audiard

Year: 2015

Two interviews on the Criterion release of Dheepan, Jacques Audiard’s Palm d’Or-winning drama, offer polar opposite interpretations of the film’s ending and ultimate tone. In the first, with director Audiard, the lives of three Sri Lankan refugees find a happy conclusion after a harrowing journey through contemporary suburban Paris. A former Tamil Tiger, the man who adopts the identity of “Dheepan” (Antonythasan Jesuthasan) shepherds two complete strangers, a young woman (Kalieaswari Srinivasan) and a preteen girl (Claudine Vinasithamby), passing them as his wife and daughter, respectively, in order to surreptitiously escape their war-torn home. Once they reach Europe, Dheepan gets a job as a super for a public housing block, thrust once more into a life of war as he must placate and eventually protect (in an explosive moment of sustained, surreal violence) his new family from the drug dealers and gangs thriving in the skeletons of the monolithic buildings in which he replaces light bulbs and cleans up garbage. Audiard, who spends much of the interview explicating the many shifts in genre his film takes—pretty pleased with himself as he describes how expertly he thought he navigated a war film, a social drama, a film verite, a thriller and a melodrama—doesn’t so much elucidate Dheepan’s overly positive ending as he does point out how he achieved what he wanted to achieve.

The second interview and second interpretation, care of lead actor Jesuthasan, proves that Audiard actually didn’t. Jesuthasan describes his take on Dheepan’s “happy” ending, that instead of finding peace, Dheepan and his new family would only find an altered paradigm of an equally difficult refugee experience: same violence, different place, never able to escape the lot in life into which they’ve been born. Jesusathan also tells the story of his own Sri Lankan departure, how he left to avoid persecution for being, like his character, a former Tiger. In the actor’s eyes, besides fathomless sadness, one can see resignation and a lifetime of exhaustion: He is always an Outsider on the run. He sees the same fate for Dheepan.

Still, Jesuthsan, untrained like many of his co-actors, has nothing but respect for Audiard, who he describes as a “friend” always willing to “refine” scenes with the actor. Dheepan, then, is a film always at odds with itself, inscrutable sometimes—which isn’t a matter of the film’s failings, but the natural affect of a filmmaker who knows nothing but empathy telling the story of a way of life he can’t ever really understand. Regardless of how one reads the ending of the film—I tend to lean toward Audiard’s pleasant intentions, because his characters do, for at least a small interval of life, seem to have found some rest—Dheepan is a film which tries to feel its way as honestly as it can through the nightmarish reality of our refugee crisis. —Dom Sinacola

Good Morning

Good Morning

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Year: 1959

The magic in Yasujiro Ozu’s lasting influence lies with his unique ability to present characters and stories that were culturally specific and universally relatable in equal measure. He was famous for almost never utilizing camera movement, using his static long and medium shots—usually with the camera placed at ground level, in order to accommodate for the Japanese form of sitting—to imply a direct window into the lives of his subjects, specifically as they related to the time period and culture. Yet the intimate and empathetic way he approached general human nature, as he told stories about the day-to-day lives of working class characters, managed to capture the goals, dreams, frustrations and joys of people all around the world. His films were windows into another culture, as well as mirrors into our own lives.

Take Ozu’s infinitely charming comedy Good Morning, a slice-of-life ensemble piece that pretty much consists of a series of vignettes centered on the inhabitants of a peaceful and quiet Tokyo suburb. Every concrete element, from the set design to the way the characters carry themselves, are specific to late 1950s Japanese culture. Yet the themes and the content of their interactions are relatable to everyone: Neighbors gossiping about who makes the most money, family members struggling to hold a job in a tough economy, children throwing tantrums when they’re not allowed to watch TV, and most importantly, the universal fact that people all around the world thinks farts are funny. (Yep, this is an “art house” film with more fart jokes than a Nickelodeon movie.)

There’s a semblance of a plot here, centered on two brothers who decide not to talk to their parents until they buy a TV set, which fits Ozu’s reoccurring theme regarding cultural differences between generations, but this plot point doesn’t begin until halfway though the runtime, and is resolved in a refreshingly anti-climactic fashion. It’s the small moments in between the subtle drama that makes Good Morning, and a lot of other Ozu works, special.

Criterion once again presents a great Blu-ray release. The 1080p transfer comes from a new 4K restoration of the film, and it almost perfectly captures the vibrant colors of Good Morning. The light amount of digital noise reduction and the inclusion of film-like grain result in a presentation that’s loyal to the source. If I have to quibble with one issue, it would be the slight amount of color trails that show up every now and again, and that’s if you’re looking really hard. The 1.0 DTS-HD track is incredibly clear and has a lot of presence, which is vital when it comes to enjoying the playful score.

The disc comes with a mini-documentary about Ozu’s handling of comedy, as well as an interview about Good Morning by film scholar David Bordwell. But the best extra is the inclusion of Ozu’s silent feature, I Was Born, But…, which shares many similarities with Good Morning, since it’s also about two brothers getting used to life in a Tokyo suburb. The transfer is not as impeccable as the main feature, and is full of dirt and scratches, but it’s definitely the best home video release you’ll get. Also, beggars can’t be choosers. —Oktay Ege Kozak

Ghost World

Ghost World

Director: Terry Zwigoff

Year: 2001

Around the time of the Juno backlash, when audiences started getting sick of Jason Reitman’s overrated overdose of quirk after its multitude of Oscar nominations, I kept trying to recommend an alternative to that film’s attempt at capturing ironically detached late teenage ennui: Terry Zwigoff’s appropriately somber, stylish, brutally honest yet surprisingly tender Ghost World. Released six years before Juno, Ghost World, adapted by Daniel Clowes and Zwigoff from Clowes’ comic, intimately captures the post-high school struggles of Enid (Thora Birch in perhaps the best performance of her career), a too-cool-for-school type who puts on a seemingly impenetrable exterior of ironic detachment as an attempt to hide her ever-growing insecurities and anxiety regarding the adult life that’s rearing its ugly head more and more as each day passes by. She’s so “cool”, that she’d call Ellen Page’s Juno a poser who sold out to a corrupted mainstream ideal of teen rebellion.

When Enid and her equally non-chalant BFF Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) see a missed connections ad in the classifieds (Remember those, printed on actual paper?), they decide to pull a prank by setting up a date with the poster. What shows up is a shell of a man, a middle-aged dork named Seymour (Steve Buscemi), whose inherent sadness immediately attracts Enid. At first, she becomes friends with Seymour because of a hint of guilt, but eventually comes around to realize that she might have feelings for him. This scares her more than anything, since it also implies that maybe, just maybe, the perfect Ms. Enid, who’s above everyone else, might not be that different from this lovable weirdo who’s into collecting old Americana and 78 RPM blues records. Zwigoff captures Clowes’ fine line between exaggerated comic characterizations and grounded regular people as protagonists. Ghost World is occupied with eccentric people, to be sure, but we all know characters who act exactly like the ones in the film, and some of us even are those people.

Criterion’s 1080p new video transfer for the Blu-ray looks spectacular, and is close as you’ll get to owning a 35mm print of the film. It sports a healthy amount of grain while steering clear of any video noise, scratches, or blemishes. The DTS-HD 5.1 audio track captures the film’s diverse soundtrack with impressive clarity. The extras range from ten minutes of deleted scenes and a new commentary track by Zwigoff, but the best supplement here is a new documentary about the film’s production, which contains interviews with Thora Birch, Scarlett Johansson, and Illeana Douglas, who plays Enid’s hilariously pretentious art teacher. Another neat extra is a sample of Clowes’ comic printed inside the package. —Oktay Ege Kozak

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project

Directors: Lino Brocka, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Ermek Shinarbaev, Mário Peixoto, Lütfi Ö. Akad, Edward Yang

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project brings six films from countries around the globe in the project’s second collection. Scorsese and the Criterion Collection continue their preservationist approach to works of world cinema that have been neglected, lost, or otherwise made difficult to find with entries from Asia, South America and the Middle East from as recent as 2000 and as early as the silent era. From prolific, socially and politically active Filipino director Lino Brocka, Insiang (1976), the first film from the Philippines to debut at Cannes, examines the harshness of the slums of Manila through the trials of one young woman. Mysterious Object At Noon (2000) is Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s experimentation with different forms of storytelling to form a sort of fictionalized documentary of his homeland’s tales. One of the last films from Kazakhstan under the Soviet Union, Revenge (1989) is director Ermek Shinarbaev and writer Anatoli Kim’s examination of how vengeance snowballs into a catastrophe that swallows multiple lives. Casting Korean and Kazakh actors, the film tells a cruel story of murder set in Korea spanning a generations-long grudge. Brazilian director Mário Peixoto’s Limite (1931) is the collection’s oldest entry and by far the most miraculous one, available as it is through the persistence of preservationists and, sadly, with some damage and missing portions. Less a coherent story than a brooding tone poem that dwells on the things that bind us, the movie follows three castaways in a lifeboat and (we presume) some of the events that lead to their stranding—all of which are shot with cinematic techniques that look decades ahead of their time in a silent black and white movie. Law of the Border (1966) is Turkish director Lütfi Ö. Akad’s gruff look at smugglers along the Turkish-Syrian border. Director Edward Yang mortgaged his house to fund Taipei Story (1985), a lament of a changing, modernizing Taiwan through a look at domestic life.

The boxed set comes with a Blu-ray versions in 2K, 3K or 4K resolution and DVD versions of each film. Each film comes fully loaded with introductory arguments from Scorsese and other film experts that provide plenty of the delicious historical context you’ll need to appreciate each gem and one-up your friends at trivia. —Ken Lowe