Doping, insider trading, high-profile affairs—these are all examples of lies that pretty much everyone condemns. We identify the people who’ve committed these dishonest acts, the cheaters, as bad people. But everybody lies, some just do it more often or on a bigger scale.

Most of us are okay with embellishing our resumes, for example, or distorting certain information on our taxes. Dan Ariely, a professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University, calls this our “Fudge Factor.” We can cheat a little bit without seeing ourselves or what we’re doing as bad. But, he says, there are many things that can change the scale of our fudge factor—“Everybody’s doing it” or “It’s not hurting anyone” are two examples—and these things also change people’s ability to be dishonest. Yael Melamede’s illuminating documentary, (Dis)Honesty: The Truth About Lies, delves into the reasons why we lie and how we rationalize it.

It’s a fascinating look at human behavior—and one that will have viewers owning up to their own personal threshold for dishonesty. If the subway attendant is gone, do you always drop the correct (or any) fare in the collection box? I’d like to say yes, but in the spirit of being honest, I have to say no.

The documentary tackles such small examples of dishonesty and argues that the vast majority of us are “little cheaters.” And contrary to what I tell myself when I don’t pay my subway fare, little cheaters actually have a much bigger economic impact than so-called “big cheaters,” because there are so many more of us. To prove its point, the film offers stats: The IRS is cheated out of more than 15 percent of its revenue every year, and insurance fraud in the U.S. is estimated to be more than $40 billion per year. Those little lies—the omissions or embellishments—clearly add up.

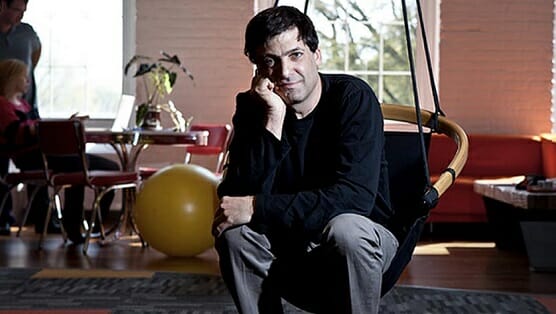

The majority of the film focuses on Ariely and the behavioral experiments he and his team have conducted over the years. These experiments, which explain our myriad rationalizations for lying, are presented by Ariely in a speech delivered at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J. While the film also features interviews with other researchers and experts, Ariely is the main attraction.

And that’s a good thing. He’s a captivating speaker who presents scientific findings in ways that are easy to understand and fun to watch. But, no matter how well it’s presented, nobody wants to watch an hour-and-a-half-long film about academic research. So Melamede wisely intersperses Ariely’s findings with real-life examples of lies told by the liars themselves. We hear from a mom who was sentenced to jail time and community service for lying about which school district her children lived in; she only wanted to do what was best for her kids. Tim Donaghy, a disgraced former NBA referee, explains the thought process that led him to bet on games that he officiated. A stock trader says it was common practice for traders to use insider information. He knew it was illegal, he just didn’t know how illegal. Now he’s serving a nine-year prison sentence.

There are obviously many different kinds of lies—Santa Claus and the 2008 financial crisis are not remotely on the same level—and they affect people in many different ways. But the film tries to convince us that there aren’t many different kinds of people. When it comes to dishonesty, there aren’t good people and bad people, just people—who lie.

The point isn’t to make viewers feel guilty about lying or how they justify their dishonesty. On the contrary. It’s a lighthearted, but nonetheless impactful, film that spends the large majority of its running time explaining this very human act. Of course, you can’t make a film about liars and cheaters without delivering some sort of message. And, in addition to hammering home that we all lie and cheat, the film also aims to prove that there are some fairly simple “cures” for lying that could benefit society as a whole. For example, in one of the experiments that Ariely and his team conducted, they found that, regardless of religious beliefs, people were far less likely to cheat on a test if they were asked to name The Ten Commandments beforehand. In other words, the more we are reminded of “right” and “wrong” the more likely we are to do right.

So will I pay my full fare the next time a subway attendant is M.I.A? Maybe. I can’t say for certain. But after watching this film, I at least know why I convince myself that it’s okay not to.

Director: Yael Melamede

Writers: Chad Beck, Yael Melamede

Starring: Dan Ariely

Release Date: May 15 in select cities