This post is part of Paste’s Century of Terror project, a countdown of the 100 best horror films of the last 100 years, culminating on Halloween. You can see the full list in the master document, which will collect each year’s individual film entry as it is posted.

The Year

1971 is a year that continues the strong run of European horror output, while crystalizing the trend toward “extreme” horror at the same time with a bevy of films that deeply challenged censors and audiences alike. There are more roots of the quietly approaching slasher genre to be found here, as well as the debut of one of the greatest populist film directors of all time. There’s simply a prodigious amount of horror cinema in general, and greater output from the U.S. than in the last few years as well. The horror genre is as popular in this moment as it’s ever been, and inarguably more transgressive at this time than at any point in the past. More and more, horror cinema is coming to represent the deviant side of a cultural divide between “serious” film critics of the day and the thrill-seeking, supposedly deviant audience members who packed grindhouse theaters and kept the flow of pulp coming.

This year certainly doesn’t want for films that stirred up controversy, as The Devils is among the most scandalous horror pictures ever released, while Straw Dogs also caused a scene, leading to accusations that it (along with the likes of A Clockwork Orange, released a few months earlier) represented a new, disturbing wave of brutal violence in American film. Sam Peckinpah’s film in particular seemed to be misunderstood in its initial release, as contemporary reviews failed to appreciate the complex motives of its antagonists and the delicate progression of Dustin Hoffman’s David Sumner from milquetoast academic to testosterone-crazed home defender. Straw Dogs is a film about difficult choices, and it doesn’t seem to offer any real opinion of its own on whether David’s choices in particular are the “correct” way, or the only way, that the ultimate confrontation could have gone down. We understand why he does what he does, but the audience’s personal detachment from the crippling affronts experienced by David (and especially by his wife) put us at a distance far enough removed to see alternate routes, or ways that violence might have been avoided—which only makes the killings seem more senseless.

At the same time, Mario Bava is experimenting with depictions of cinematic death that are meant to be consumed in a considerably less challenging, more titillating way, in his important proto-slasher, A Bay of Blood. In terms of structure, this is very nearly a true slasher film, sprinkling stalking and grisly kills (replete with bright red rushes of blood) among a cast of characters gathered at the titular bay. Several of its death scenes would be repeated almost exactly in Friday the 13th Part 2 in particular, most notably the sequence in which two young lovers in mid-coitus are simultaneously killed by a spear that impales both. The only thing that keeps A Bay of Blood in the giallo rather than slasher camp, in fact, is its focus on mystery and concrete, real-world motivations for the killings, which revolve around financial gain rather than demented sport. Still, it’s clear that the true slashers are almost upon us now.

1971 is also home to an array of other notable films, including Duel, the feature-length horror-thriller debut of Steven Spielberg, along with Vincent Price’s classic, campy revenge story The Abominable Dr. Phibes and another Cushing and Lee anthology film from Amicus, The House That Dripped Blood. Truly, there’s too much good stuff here to even list it all.

1971 Honorable Mentions: Straw Dogs, A Bay of Blood, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, Duel, The Abominable Dr. Phibes, Twins of Evil, The House That Dripped Blood, The Omega Man

The Film: The Devils

Director: Ken Russell

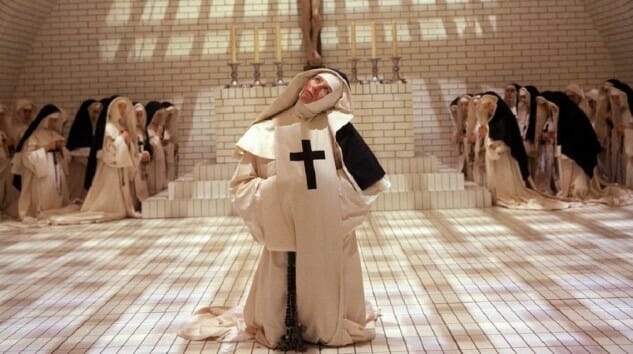

There’s little doubt that Ken Russell’s The Devils is among the most audacious historical dramas/horror films ever made, featuring striking performances, elegant cinematography, and yes—an incredibly depraved, sacrilegious stance toward the church. Even in its heavily edited state, it’s a film that still needs to be seen to be believed, and remains one that many film aficionados simply choose to ignore from a comfortable distance. The “uncut” version of The Devils, likewise, is quite difficult to lay one’s hands on, but it contains scenes that are all the more shockingly explicit and powerful. This is a film that truly redefined the nature of trying to provoke a reaction via outrage in cinema.

The Devils is based on Aldous Huxley’s 1952 text The Devils of Loudun, concerning a case of supposed mass demonic possession that struck a convent of Catholic nuns in the city of Loudun, France in the 17th century. The true root of the possessions was unsurprisingly a political one, as the royally backed governors of the region wish to tear down the city’s fortifications to prevent the local Protestant population from being able to fortify the city against the crown. Standing in their way is Catholic priest Urbain Grandier, who is betrayed by a jilted, hunchbacked nun who is secretly in love with him, and accused of crimes that include an array of supposedly devilish doings.

As Grandier, English star Oliver Reed gives a performance for the ages; a magnetic tour-de-force delivered with dramatic, Shakespearean overtones. Grandier is a self-obsessed and worldly man of the cloth, fallen from the pure of faith no doubt, but with the safety of the populace as his primary objective. Women are drawn to him, and understandably so—he possesses a rugged masculinity and commanding presence the Latvian Orthodox priests on Seinfeld would no doubt have termed “the Kavorka.” Every time Reed speaks, the people around him listen, and he holds the audience in rapt awe. Russell highlights this well, especially in one sequence as he cross-cuts back and forth between Grandier stirring up the townspeople and a duplicitous cardinal inciting the king against Grandier and the city of Loudun.

Actress Vanessa Redgrave, likewise, is stunning as the deeply repressed and pathetic sister Jeanne de Anges, the hunchbacked sister who eventually leads a crusade against Grandier, roping in the rest of the nuns along with her. Together, they’re forced to perform wild feats of hedonism as proof of their possession by the devil, in order to absolve themselves of responsibility for their behaviors. They play-act these behaviors with reckless abandon; pawns in the church’s game to dispose of Grandier and subdue the city. Redgrave emotes both guilty piety and a lust she knows she’ll never be rid of, and is quickly consumed by both.

The singular images of The Devils range from the profound to the patently absurd—at one point a man with a sword fights another one holding a stuffed crocodile—but they’re impossible to forget. Mountains of corpses tumble into pits, the result of horrific depictions of the agony of the plague. Disorienting fantasy and dream sequences openly mock sacred Christian imagery. It’s a true fever dream of a film, suffused in sweat, tears and mucous. If you feel the need to take a shower afterward, you’re likely not alone.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident horror guru. You can follow him on Twitter for more film and TV writing.