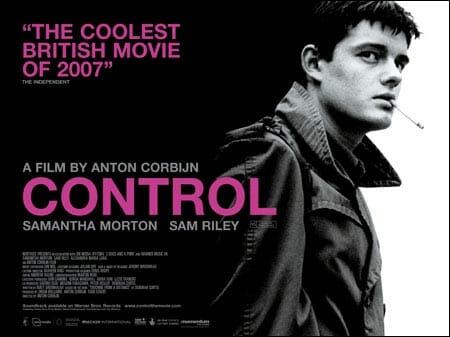

Release Date: March 25

Director: Anton Corbijn

Writer: Deborah Curtis and Matt Greenhalgh

Cinematographer: Martin Ruhe

Starring: Sam Riley, Samantha Morton, Alexandra Maria Lara

Studio/Run Time: Weinstein Company/ 121 mins.

The ?rst time I ever heard Ian Curtis’ voice was when “Transmission” popped up on a compilation. Trans?xed by its cold angularity, its hectoring ?atness, I couldn’t help but shudder. Unlike, say, Morrissey, who ?oors you on ?rst impression with stylistic choices, Curtis lands on a different point in the psyche. His voice claws out for you with surgical precision and a claustrophobic sense of desperation. Even before you know he committed suicide, there’s something morbidly otherworldly about his low echoing moan. It’s beautiful, unforgettable and it draws you to try to learn more about the creature that uttered it. It’s a harder task than it sounds. While, musically, Joy Division is widely recognized as the brooding omnipresence behind the evolution of English post-punk, the mystery of Curtis has never been untangled. Drawing from wife Deborah Curtis’ autobiography Touching From A Distance, director Anton Corbijn seeks to do something of the sort in Control. It’s hard not to approach this ?lm with a certain amount of trepidation. Rock biopics, even good ones, tend to either reduce their subjects to clichés or oversimplify their stories in the service of narrative coherence. Beyond that, Sean Harris’ brilliant, glancing portrayal of Curtis in 24 Hour Party People seemed de?nitive despite a dearth of screen time. Visually, though, Control’s Sam Riley (who played Fall singer Mark E. Smith in 24 Hour Party People, as referenced in a deliciously subtle inside joke in Control) is a double-take inducing ringer for Curtis, so some of the sting of the comparison is de?ected. Plus, Curtis’ tonal role in the two ?lms is strikingly different. In the freewheeling whimsy of 24 Hour Party People, Curtis’ character was simultaneously a freakish curiosity and a gesture toward the darker seams of reality just outside the fun. Control turns the mood of the story on its head, using a peckish Tony Wilson who has just signed an agreement in blood as one of the few sources of levity in a story that otherwise portrays the band’s inner life as anxious and banal. While elegantly constructed (Corbijn’s skill as a still photographer is ubiquitously apparent), Control takes a moment to ?nd its footing. In its early stages it casts Curtis as an erratic, artistic rebel along the lines of Jim Morrison. All bravado, ego and poetry, Curtis edges out his best friend to win the heart of soon-wife Deborah. Suddenly the tone shifts, and a suburban malaise appears to replace the rocker’s swagger with intense introversion. Soon Curtis joins Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner’s band (then Stiff Kittens, about to be Warsaw, and eventually Joy Division) while exiting the Sex Pistols’ legendary 1976 show at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. From there on, the band operates as an immutable but sometimes ominous backdrop to Curtis’ life, and Control oddly assumes the essential inevitability of Curtis’ place in the band without showing much interest in the band itself. While live performances, studio sessions and VAN trips comprise much of the movie, in Control Joy Division is part of the scenery—at most a foil for Curtis’ increasingly tormented personal life. Curtis’ pain is apparently drawn from two sources. The ?lm focuses primarily on the cognitive dissonance between the emotional tug of his love affair with Belgian fanzine writer Annik Honoré and his shame over the neglect of his wife and child at home. In addition, uncontrollable and terrifying epileptic seizures punctuate his sense of helplessness and self-loathing. The demand for his presence onstage and an upcoming tour of America add additional pressure, and Curtis’ melancholy, generally expressed by silence, pervades the ?lm. Control is smart both in its refusal to engage in cloying hero worship of Curtis and also in its unwillingness to overdramatize his decline. There is no wrenching build-up to the suicide—it just happens. Still, the ?lm’s thoughtful frigidity raises more questions than it answers. While it doesn’t oversimplify or typecast him, Control struggles to give the audience true access to Curtis. Based in essence on a book written by a wife who battled to know her husband and possibly never truly did, the ?lm operates at a remove that often makes his story two-dimensional. Riley’s deadpan evocation of the man is brilliant for its likely realism, but it fails to risk too searching a guess as to what really operated behind the mask, and why he took that ?nal leap. In the end, Control does all it can do, which is skate us across the surface of a lost poet whose inner life remains mysterious even to those who knew him best. The implication, perhaps, is that if there are deeper insights to be had, the best source may be his songs, and the haunting, trenchant voice that sang them.