Thirty-five years ago this month, Michael Mann’s Manhunter slipped into theaters. A crime drama with no big names—at least then—in its cast, the $14-$15 million movie was a flop, grossing somewhere around $4 to $6 million. You could say the movie was the first instance of the wave of grisly, serial-killer films that would clutter multiplexes in the ’90s and ’00s. It’s definitely the first movie that introduced audiences to that serial killer who just won’t die: Dr. Hannibal Lecter.

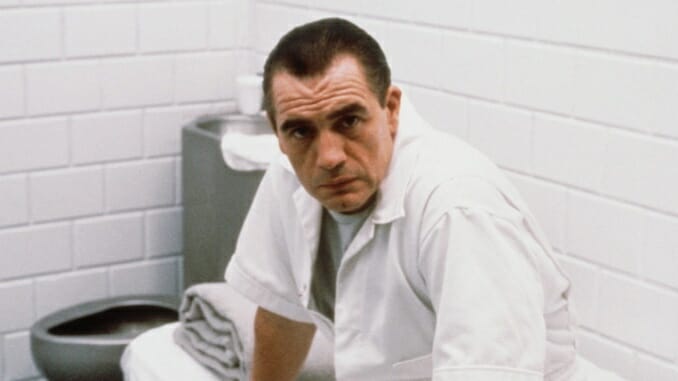

Based on the 1981 novel by Thomas Harris, Red Dragon, Manhunter is where Lecter (whose last name is spelled Lecktor in this film) makes his first appearance. In Mann’s film, the role so closely associated with Sir Anthony Hopkins for decades is played by another acclaimed British actor—future Succession patriarch Brian Cox.

A supporting character in Manhunter, the clever, calculating cannibal Lecktor still holds a grudge that he was caught by Will Graham (William Petersen), an FBI profiler still haunted by Lecktor’s physical and mental scarring. Graham is on the trail of new killer Francis Dollarhyde (Tom Noonan)—nicknamed “The Tooth Fairy” for his tendency to leave bite marks on victims—and comes to the incarcerated Lecktor for consultation.

Manhunter is basically a cinematic continuation of what Mann (who spent the ’70s writing for TV shows like Starsky & Hutch and Police Story before directing his 1981 feature debut, Thief) was doing on television at the time, show-running the cool cop dramas Miami Vice and Crime Story (which starred Manhunter cast members Dennis Farina and Stephen Lang). Back then, Mann was trying to bring style and substance to bland, prime-time TV, producing police procedurals that were all about mood, visuals and storytelling that took its time.

Those are the main elements of Manhunter, a movie that’s cool to look at but still makes you feel uneasy while watching it. It begins from the killer’s perspective, as he creeps up a flight of stairs and literally shines a flashlight on his poor, sleeping prey. That’s certainly a creepy-ass way to start a movie.

And, yet, this is also Mann showing the audience how Graham starts an investigation, diving into the killer’s point-of-view and figuring out how the son-of-a-bitch did it. It’s a road Graham, who would rather be living the retired life on the beach with his family, doesn’t like traveling down. But, if he wants to catch this guy before he strikes again, he has to fully get inside—to borrow a Geto Boys song title—the mind of a lunatic.

Mann worked with cinematographer Dante Spinotti, who would work with Mann on later films (as well as Red Dragon, that other adaptation of the book, which also starred Hopkins as Lecter), in creating a visual tone full of color tints. Scenes with Graham and his wife (Kim Greist) were set in “romantic blue,” while the movie’s unsettling moments were done in a green hue, with some purple or magenta thrown in.

As for the plot, the movie cares less about hitting you with bloody, gory elements and more about showing you the intense, dedicated process Graham and his fellow FBI agents (which include such familiar TV faces as Life Goes On’s Bill Smitrovich, Frasier’s Dan Butler and longtime David Letterman crony Chris Elliott) go through to find this guy. Despite having forensic science on their side, they always appear to be one step behind Dollarhyde, who we later see in the second half trying to achieve some sense of normalcy by having a relationship with a blind co-worker (future Oscar nominee Joan Allen).

Mann and the cast went in hard on the research. Before filming began, Mann spent time with the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, and corresponded with imprisoned murderer Dennis Wayne Wallace, who inspired Mann to include Iron Butterfly’s “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” in the chaotic, climactic shootout. (Wallace claimed it was the song of choice for him and his imagined lover.) Petersen consulted with the Chicago Police Department Violent Crimes Unit and the FBI Violent Crimes Unit, while Allen met with representatives of the New York Institute for the Blind. As for Cox, he based his Lecktor performance on Scottish serial killer Peter Manuel, who felt “he didn’t have a sense of right and wrong.”

As much as Manhunter has a visual aesthetic that can be described as impeccably ’80s, the narrative tone is reminiscent of ’60s and ’70s cop dramas like The French Connection, Bullitt and The Boston Strangler, where it isn’t about the action as much as it’s about the hunt. Cops tracking down criminals would go on to be a running theme in Mann’s work, from Heat to Public Enemies to his eventual big-screen adaptation of Miami Vice. As Sean Burns wrote about these films in 2015, “The chase is the thing; cat and mouse games played by obsessively driven pros who define themselves by being the best there is at what they do. Character is action, but actions have consequences.”

As Hollywood later gave us more gruesome, more successful, psycho-thrillers like Seven and The Silence of the Lambs (which, of course, gave us Hopkins’s initial, Oscar-winning turn as Lecter) and even television would have more in-depth police procedurals (like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, which would star Petersen), it was Mann and Manhunter that proved you can make a compelling story out of people who go through hell and back just to put an end to the evil that men do.

Manhunter is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel and Shudder.

Craig D. Lindsey is a Houston-based writer. You can follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @unclecrizzle.