If you crack a history book to brush up on the Stonewall riots, you might stumble across the names of gay and transgender activists Sylvia Rivera, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy and Marsha P. Johnson. If, once you’ve finished your fact checking, you decide to take a peek at the cast list for Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall, an ostensible biopic about that landmark 1969 gay rights demonstration, you’ll find that Rivera and Griffin-Gracy don’t even show up as footnotes. If, after all of that, you still decide to corrode your soul by watching the movie, you’ll notice that Johnson (Otoja Abit) shows up as barely a bit character in the depiction of her own struggle, led, in Emmerich’s vision, by a clean-cut well-to-do white boy.

By the time Emmerich gets to the riots, which takes about 100 minutes of the film’s 120-minute running time, you’ll want to chuck a cinder block at the screen. Describing Stonewall as merely a crummy biopic would be like describing Pasolini’s Salo as a rom-com. For this film, “crummy” would be an improvement: What Emmerich has done is unwittingly flip the bird at the foundation of the modern gay rights movement. Before the movie even opened, the streets of social media were already mobbed with indictments of his efforts, and, like any fire worth its accelerant, all he’s managed to do by coming to his picture’s defense is hasten the blaze. His reply to critical response is appalling, but it illustrates the foundation of misunderstanding he’s built Stonewall upon.

There are two stories at play here. The first is about late 1960s political and social attitudes, marked by the consequences of the era’s panicked homophobia. The second story takes a ground-level perspective on those attitudes, as young Danny Winters (Jeremy Irvine) is outed among his Indiana high school classmates and subsequently disowned by his football coach father (David Cubitt, who helpfully wears a cap that reads “coach” in case we forget his occupation). So far, so heartbreaking, but the film mashes its intertwining plots together less elegantly than Victor Frankenstein stitches together corpses. (Incidentally, that allusion also aptly describes the film’s torpid visual scheme.)

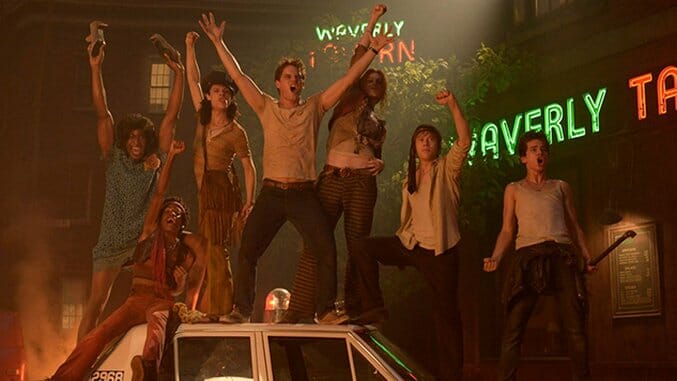

Emmerich wants Danny to be our “in” to the events that lead to the Stonewall riots. This, on the page, is a harmless, tried-and-true storytelling device: Insert audience identification character into a setting and anchor our perspective to him or her. But Danny is a big, hunky slab of bland engineered to make white moviegoing audiences feel less threatened or alienated by the culture Stonewall portrays. We never really get a sense of him as a character, even when he’s making overwrought outbursts about whatever circumstance over which Emmerich and screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz demand he lose his temper. Danny reacts to conflict as the movie requires him to. Danny isn’t a character—he’s clip art. One second he’s not sure where he fits into the battle for gay rights. The next, he’s stirring up mob violence with his pal Cong’s (Vladimir Alexis) trusty brick.

Stonewall has already caught flak for putting that brick in Caucasian hands, though accounts of the riots don’t conclusively identify who wound up throwing it. In the absence of a definitive inciting figure, Emmerich and Baitz take the easy way out by inventing Danny instead of choosing any of the gay folks, white or black, who were present for the riots as their protagonist. (The film’s most viable lead: Breakout star Jonny Beauchamp, who plays Danny’s unrequited crush Ray with tragic intensity.) This is old hat for Hollywood: Minority characters are either erased or pushed to the margins to make way for a fictitious white savior. In Stonewall, the decision is as egregious as it is unnecessary: Patrick Garrow shows up to play the gay rights activist Bob Kohler for a role that’s roughly 8% meatier than Abit’s turn as Johnson. The minimization of their contributions to the cause would be shocking if that practice wasn’t so routine in movies of Stonewall’s persuasion.

The actual movie isn’t any good, of course, so Emmerich’s faux pas just add outrage to injury. Baitz writes dialogue so absurdly ham-handed you might imagine he’s never had a conversation with another human being in his life. There’s a version of this movie where the tone suits the over-the-top scripting, but Emmerich can’t decide on whether he’s aiming for a schmaltzy studio melodrama or a po-faced historical biopic, and no matter what mode the movie leans toward, Baitz can’t match its tenor. The lines meant to tickle us fall flat; the lines meant to rouse our hearts just make us laugh. (You could make a drinking game out of Stonewall’s hilarious confabs, but you’d need to keep emergency services on speed dial.)

Getting a bead on Stonewall is nearly impossible. When the focus falls on the actual rioting, the movie threatens to start working, but those scenes are bafflingly fleeting. Emmerich spares so little time for the stuff that’s actually germane to his title that his tribute feels dismissive. Scuttlebutt suggests that Stonewall is his long-in-the-making passion project, but if that’s true, he didn’t bother evolving that germ of an idea beyond 1990s sensibilities. In that respect, the film is progressive: Now, Hollywood makes standard issue biopics for LGBT audiences, too. But if Stonewall takes them two steps closer to equality, it sets their cause back by several decades in the process. Just go re-watch Pride.

Director: Roland Emmerich

Writer: Jon Robin Baitz

Starring: Jeremy Irvine, Jonny Beauchamp, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, Ron Perlman, Caleb Landry Jones, Otoja Abit, Atticus Mitchell, Joey King

Release Date: September 25, 2015

Boston-based critic Andy Crump has been writing online about film since 2009, and has been scribbling for Paste Magazine since 2013. He also contributes to Screen Rant, Movie Mezzanine and Badass Digest. You can follow him on Twitter. He is composed of roughly 65% craft brews.