Gap Year: L’Age d’or (The Golden Age) (1930)

Buñuel and Dalí’s surrealist satire drove actual fascists to riot.

Movies Features The Golden Age

So that he can go on about it constantly at dinner parties (that he’s forbidden from attending—social distancing!), Ken Lowe is taking a gap year! Join him for this monthly feature throughout 2020, seeking out the essential, the classic, the weird, and the infamous films of a foreign country. This year, the spotlight is on France.

You have enemies? Why, it is the story of every man who has done a great deed or created a new idea. —Victor Hugo

Film is art, and that it is art has not been a subject for debate since before any of us were born. Art makes you feel things, and that means some art makes enemies. It’s a realization the videogame industry is coming to slowly as its leaders release games that are about men in uniforms killing folks under government orders and then turn around and plead ignorance of any “politics” in their games.

And just like videogames, film was once a medium that originated as something of a sideshow attraction or a magic trick. By the time the two Spanish filmmakers Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí got together in Paris to envision L’age d’or, however, there was little debate over the fact film could be an artistic endeavor. By 1930, the 26-year-old Dalí had become part of the Surrealist artistic movement, been disowned by his father, and already collaborated with Buñuel on their more famous endeavor, Un Chien Andalou (1929), known to most folks as “the one where somebody slices their own eyeball on camera.”

L’age d’or was Buñuel’s first feature-length film, his first with sound, a prominent example of the subversive Surrealist movement sweeping Europe, and an inducement for right-wing zealots to riot in theaters and burn museum pieces. If that isn’t art, what is?

After opening with creepy, documentary-like footage of scorpions that includes a rat getting stung, L’age d’or follows a company of dejected Majorcan soldiers barely surviving during an invasion. The victorious invaders colonize the island and an important-looking official starts lecturing an assembled crowd of civilians on how great the island’s soil is for making cement.

The film finally finds its main subjects in a man (Gaston Modot) and a woman (Lya Lys) who are discovered fornicating in the mud near the conquest ceremony. We learn, after he’s dragged away by suited authority figures, that he in fact is a Majorcan with supreme diplomatic immunity, sent on a mission of peace. We also learn—as he stamps on insects, kicks blind old men, and leers at every picture of a woman—that the only thing he wants is to have sex with his ladyfriend, and anything and anyone in his way means less than nothing to him, his mission included.

The central portion of the movie, which follows The Man’s misadventures and plumbs the depths of his shocking pettiness, is the closest thing the movie has to a narrative through-line. It still finds time to make delightfully weird digressions, as when the movie briefly follows The Woman as she tries to prepare a party in her palatial estate and must inexplicably evict an actual cow from her bed.

The Man is able to shake off the men arresting him when he presents them with his diplomatic paperwork, and immediately we flash back to his induction ceremony, where the Majorcans vest him with authority and all their hopes for peace. When we cut back to him, he hails a cab, kicks aside a blind man who was trying to hop aboard, and rushes off to try to rejoin The Woman.

At the party, they are kept apart by their parents. (Her father is an immaculately dressed older man with flies all over his face, and nobody says anything.) The well-to-do family’s servants aren’t doing much better: One maid falls dead into the main area of the house as a gout of flame erupts from the kitchen, to no reaction. Another servant outdoors is playing with his son, but when the kid annoys him, he gives him both barrels of his shotgun—it’s unclear whether the police are going to do anything about it, but the assembled bluebloods spare a moment to gawk and tsk-tsk.

Eventually The Man gets his woman, though as we suspect it’s not a happy ending that lasts for any length of time. He’s called away to be yelled at by his boss for utterly failing in his mission, but of course he doesn’t care. His eye wanders to the perfect feet of a marble statue, and The Woman’s eye wanders to the elderly conductor of an orchestra playing at the garden party. The Man pitches a fit at her infidelity, of course.

A protégé of Jean Epstein (whose L’auberge rouge we examined earlier), Buñuel wanted to take specific aim at the hypocrisies and absurdities of Gilded Age society at a time just before the Great Depression was felt fully in France. Despite the disjointed nature of a lot of the scenes across the movie’s hour-long runtime, the central ethos of the movie is very coherent: Two horny, superficial obscenely rich and privileged people are kept apart by the stuffy politics of a horny, superficial, obscenely rich and privileged era.

There’s also no ambiguity about who pays for the whims of those privileged lovers: the women, children, poor and politically disenfranchised.

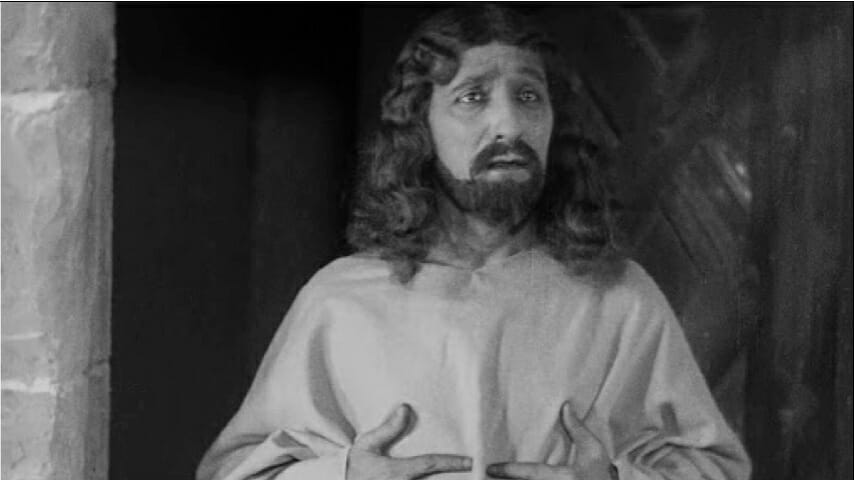

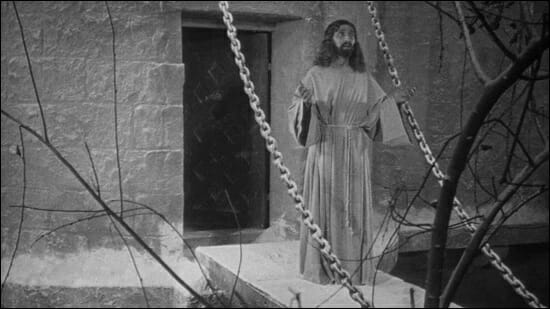

The last scene of the movie is a completely context-free vignette in which the titles explain that a group of hedonistic aristocrats are coming out of confinement, having debauched a group of young girls and women. Their leader looks like Jesus, and as he strides immaculately from the interior of his fortress, he pauses for a moment to go back and kill one of the surviving women. The final shot of the film is a cross hung with the scalps of women.

Besides its status as a landmark film for one of French cinema’s major luminaries, The Golden Age was also the source of controversy, behind the camera as well as on the silver screen. Buñuel and Dalí parted ways during the work—Buñuel wanted a blistering screed against society’s absurdities, and Dalí is said to have balked at the anti-Catholic imagery.

The reception was quite an event. Right-wing extremists vandalized the theater on opening night, the Pope threatened the film’s financiers with excommunication, and the local prefect of police banned further screenings of the film. It was pulled from all circulation in 1934 and would not grace the inside of a theater again until 1979.

Was it worth all that furor? The movie is now part of cinematic canon. It’s unlikely that this year’s The Hunt, also the target of ire from the powerful, is going to go down in history with as much reverence as this film, but the controversy over it will always, always seem stupid.

Kenneth Lowe is an arachnid species found in warm parts of the Old World. You can follow him on Twitter and read more at his blog.