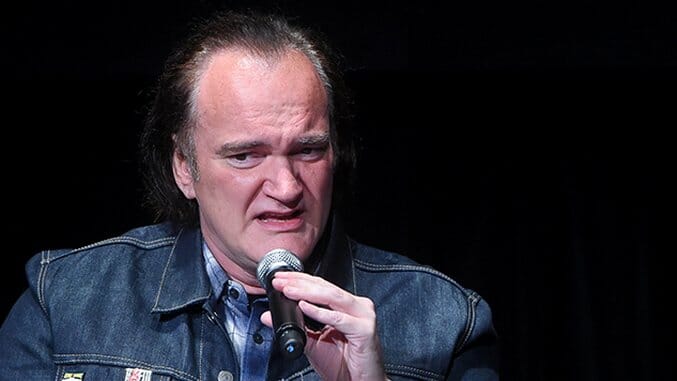

Paste at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival

Photos: Jamie McCarthy / Getty Movies Features Tribeca Film Festival

If it’s your first visit to New York City, let me make a recommendation: Don’t cover the Tribeca Film Festival. It’s simply too extensive, varied and dispersed for you to spend your time being a tourist. It’s a fest for industry veterans, zealot volunteers, locals, professionals and those chauffeured from hotel to red carpet. It’s sink-or-swim in this sea of media, with both options ending with you soaked.

Sixteen years in and the annual Tribeca Film Festival still hasn’t seemed to solidify its mission. Is it to sell new films? Spotlight new voices? Celebrate the mélange of new and weird media that artists churn out in the hopes of financial or spiritual survival? The clues are found in a schedule packed full of VR, short films, celebrity-on-celebrity interviews, teaching seminars, youth-focused industry events, videogame showcases and eccentric guest speakers. And, oh, feature films.

Tribeca’s attitude seems niche and strange, though it’s obscured by the gigantic size to which the fest has grown. The multi-week festival feels at odds with itself—a theme reflected in its many films about soul-searching quests. Wonderfully fiery documentary Copwatch sees justice activists become villains and then back to activists again, while period drama Pilgrimage sees the same, only with monks and warriors. Dog Years (Burt Reynolds basically plays himself) and Rock’n Roll (Marion Cotillard plays herself) are self-reflexive questions of identity within the film industry, while Saturday Church and Super Dark Times explore the more general confines of the coming-of-age story.

My journey began, as many do, with a new friend. I have a Dungeons and Dragons group with a motley group of film geeks that plays online twice a month. When one (our dragonkin paladin if you’re being nosy) heard I was heading to Tribeca, he offered me his Brooklyn couch for my stay. It’s both the dorkiest way to save money on a hotel and the most appropriate for Tribeca’s varied festivities. Meeting up at rooftop bars or birthday parties with acquaintances from Twitter made the meld of digital and physical in my own life even more apparent. Virtual friendship was about to become a reality, no visor needed.

I skipped Michael Moore’s speaking engagement at the 18th anniversary of Bowling For Columbine so I could refresh my airplane-strained nerves with my host and a basement burger in Williamsburg rather than a heart-wrenching doc in Manhattan. At this point I’d already picked up my badge, gotten lost in the bowels of the Tribeca hub building (at one point accidentally ending up on a “secure” floor for Verizon employees that looked like a zombie film set) and taken in a movie with a friend who had up until that screening only been an online colleague. I was ready for a break.

The small conversation, two film nerds slowly branching out and bonding over new topics, felt like a step in the right direction. Friendships can start with only one shared point of interest, but they can’t sustain off one shared interest alone. Tribeca seems to take a similar stance towards its community, wishing to be the multi-faceted answer to its neighborhood’s artistic needs. The fest’s eclectic programming certainly reached a diverse audience: I sat in packed crowds for schlocky creature feature Devil’s Gate and intense feminist justice doc I Am Evidence, for Thumper and Sweet Virginia, dour crime thrillers dabbling in similar aesthetic swatches. Crowds were electric for every one, abuzz with glee and sorrow, affected yet disparate. If they didn’t screen down the hall from each other or have the same pleasant volunteers outside badgering attendees to download the same proprietary app, you’d never believe they were at the same festival. The only thing in common was response. People love the community; Whether they weep or gasp, they want to do it together.

There was something there for everyone—and countless things there for no one at all. The popularity of some events, including a conversation between Scarlett Johansson and Jon Favreau, prevented oversold ticketholders from seeing what they paid for. Irate customers threatened volunteers and had to be escorted out by security, presumably ushered to a less popular VR experience or student short film collection at no charge.

I was one of the people that missed out, but I instead decided to take the newfound downtime to experience New York away from the movies and near something much closer to my heart: pizza. I ordered a Sicilian slice next door to the theater. It was like Chicago deep dish, but instead of my hometown’s casserole content, it was thick, fluffy crust all the way through with a cheesy top, like pizza cake. I ate outside the small two-table pizzeria until someone tapped on the window. “What’re you eating out there for?” a large bankerly fellow asked, patting the open seat next to him. “Are you a horse?” Drawn in by the strangeness of the invitation and the goodwill in my heart generated care of the purity of pizza, I joined him.

This stranger had a lot to say and seemingly nothing but time and pizza over which to say it. In the course of our conversation, he learned that I originally hail from Oklahoma and I learned that he’d been reading about Warren Buffett—which he brought up because all he knew about Oklahoma was that Buffett lived in Omaha. I didn’t have the heart to correct him. The pizza was just too good.

We talked about movies, of course, and from his previous mention of Buffett, segued to his philosophy towards legacy: “Nobody remembers the moneymakers. They remember the starving artists.” He also told me Buffett owns Geico (which I looked up later and confirmed after his Omaha claim) and that the company was founded over 80 years ago. I said that if nobody remembers Buffett, they’d at least remember Geico. He replied that he hoped I saw some movies at Tribeca that had the same staying power as Geico. I like to think I did. Most art is basically just us trying to outlive Geico, after all.

That seemed to be the impulse behind Johnny Rotten’s documentary The Public Image is Rotten, which allowed the aged rocker an opportunity to assess himself as a whole. Even if he second-guessed the film during the post-screening Q&A, Rotten embraced his new role as an ex-punk. Ex-anythings have a certain power once they accept it. Clarity comes when pride fades. I began to understand this once I realized I’d never attend all the films I’d promised myself I’d see.

Going in blind, making your schedule based on time slots rather than content, can be a blessing and a curse. I was constantly surprised, which made my highs higher and my lows lower. Good movies were elations, fireworks from nowhere, like Dabka. Dabka is a film about Somalia told via the only Somali thing anyone pays attention to: pirates. And it’s razor-sharp about this point. Moxie is a dangerous element for films because a misjudgment in serving size can be deadly. A perfectly fine film can drown in smarm. Dabka finds the balance between damning its own cheekiness and reveling in it. Its director also provided me with my first “off the record” interview moment, which, although it still feels like a journalistic achievement, made my blood run ice cold.

You also find surprise bombs that drop your heart lower and lower in your body until you’ve found yourself physically slumped in your chair. Paris Can Wait was the ultimately insulting bad movie, dragging its tepid romantic cross-France trip through molasses so decadent that my rumbling stomach forced me to stay awake throughout its excruciating runtime. No amount of smuggled bodega munchies could combat that kind of despair.

The miserable weather didn’t help, spreading its rainy melancholy to the city’s hurried residents, a throbbing mass outnumbered by the growing population of discarded gutter umbrellas. Brightly-vested charity workers were the only ones stationary, prowling the wet Chelsea streets leading up to the festival back-to-back, buddy cop style so no pedestrian could pass in either direction without avoiding eye contact. Another creative, ambitious, persistent group—right on the borders of another—that seems to know how to make people notice, but not how to get what they want.

Nevertheless, the city thrummed near the festival hub, even cab drivers sucked into the red carpet starfuckery. Picked up for a desperate time-crunched drive from Saturday Church’s ending credits to an interview with its cast and director, I found myself with a cabbie primed to discuss his brush with celebrity. “You’re with the festival. Are you an actor?” Up until then, the closest I’d gotten to being confused for an actor at the festival was when Paul Sorvino and Martin Landau decided I looked like a young Ben Gazzara.

The cabbie continued (not needing my input), “I had an actor in here once. A famous one. Told me I’d get a $50 tip if I knew his name. I knew it was an American car, so he said $50 if I got his last name. I had it down to Pontiac, Ford, and Chevy. I guessed Ford. He said I was right and there’d be another $50 for me if I got his first name.”

I’d seen twenty-six movies in four days and this guy didn’t know Harrison Ford. You could say it was a cold splash of reality. “I took a stab in the dark: Leonard. Sonofabitch laughed but still gave me the fastest $50 I’ve ever made.” There’s something beautiful about the confluence of cultural bubbles inside and around Tribeca. Some people know all the films, some are just living their lives adjacent to the culture. The fest’s broadening perspective wants all of them.

Jacob Oller is a writer and film critic whose writing has appeared in The Guardian, Playboy, Roger Ebert, Film School Rejects, Chicagoist, Vague Visages and other publications. He lives in Chicago, plays Dungeons and Dragons, and struggles not to kill his two cats daily. You can follow him on Twitter.