Lynne Ramsay has a reputation for being uncompromising. In industry patois, that means she has a reputation for being “difficult.” Frankly, the word that best describes her is “unrelenting.”

Filmmakers as in charge of their aesthetic as Ramsay are rare. Rarer still are filmmakers who wield so much control without leaving a trace of ego on the screen. If you’ve seen any of the three films she made between 1999 and 2011 (Ratcatcher, Morvern Callar, We Need to Talk About Kevin), then you’ve seen her dogged loyalty to her vision in action, whether that vision is haunting, horrific or just plain bizarre. She’s as forceful as she is delicate.

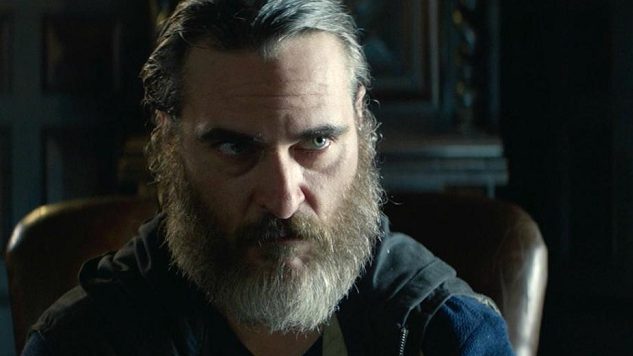

Her fourth film, You Were Never Really Here—haunting, horrific and bizarre all at once—is arguably her masterpiece, a film that treads the line delineating violence from tenderness in her body of work. Calling it a revenge movie doesn’t do it justice. It’s more like a sustained scream. You Were Never Really Here’s title is constructed of layers, the first outlining the composure of her protagonist, Joe (Joaquin Phoenix, acting behind a beard that’d make the Robertson clan jealous), a military veteran and former federal agent as blistering in his savagery as in his self-regard. Joe lives his life flitting between past and present, hallucination and reality. Even when he physically occupies a space, he’s confined in his head, reliving horrors encountered in combat, in the field and in his childhood on a non-stop, simultaneous loop.

The last of these is the essential fuel of Ramsay’s narrative engine. Joe spends his days as a hatchet man with a heart of tarnished gold. He’ll kill a man for money, but only if the man traffics young girls. As stone-cold assassins go, Joe’s one of the good ones (or at least one of the better ones). We meet him as he briefly suffocates himself after completing a job, then goes about cleaning up the crime scene, leaving it spotless before heading to a payphone to make an anonymous call to his client. (Therein lies the title’s second layer. A good contract killer knows to cover their tracks. Joe’s a pretty good contract killer.) So far so good. It’s when Joe takes his follow-up job recovering Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov), the daughter of New York State Senator Albert Votto (Alex Manette), that everything goes to hell. Joe’s already unstable world collapses.

The Votto ordeal thrusts Joe into a seedy political underworld quite content to murder anyone deemed a threat to its concealment. Unsurprisingly, the ensuing chaos is a perfect trigger for Joe’s PTSD, sending him on a nightmare spiral of suicidal delusion. Blood is shed. Skulls are cracked. Psyches are shattered. As Joe unravels over the twin stresses of failure and personal loss, Ramsay finds her “in” to the film’s hitman subgenre. You Were Never Really Here prioritizes character study with a greater urgency than even the best hitman flicks. Together, Ramsay and Phoenix pinpoint in Joe the human bereavement that’s key to her cinema: Ratcatcher’s portrait of innocence lost to class struggle in 1970s Glasgow, Morvern Callar’s sociopathic crisis of identity, We Need to Talk About Kevin’s tale of tainted maternal bonds and the consequences infamy visits on the guiltless.

Phoenix also pounds dudes to death with a ball-pein hammer, so if you watch films like You Were Never Really Here for bloodshed, there’s that. But the literal violence veils emotional violence, the kind of torment people suffer on a molecular level, which underscores Ramsay’s decision to skirt fight scenes. Battered flesh offers flash in the pan shock value, while a battered spirit is uglier by far. We never quite glimpse Joe go about his grim business. Ramsay prefers to watch him at a distance, from overhead, through security camera footage. He kills off-screen, and we observe his victims after the fact, dead on the ground as blood pools under their bodies. (Therein lies the title’s third layer. Joe kills without detection, leaving only corpses as confirmation of his presence.) The effect is infinitely cooler than a routine slick action sequence.

Ramsay isn’t necessarily playing it cool as much as she’s chilling our bones, though. You Were Never Really Here is a deeply unsettling movie heightened by Ramsay’s signature flourishes: Deliberate, steady camerawork (by Thomas Townend) married with bursts of kinetic editing (by Joe Bini), anchored by a quietly towering performance from her lead, and overlaid with a rattling score (by Jonny Greenwood). If an argument for Ramsay as a great collaborator must be made, then that argument must be couched in how You Were Never Really Here finds harmony in cacophony. The film maintains a precise volume of noise, of recurring trauma, when wrapped in Joe’s perspective, disrupting his mental clamor for only brief reprieves: a touching moment at home with his mother (Judith Roberts) here, a conversation with his handler (John Doman) there.

These moments are few, and without revealing too much, they don’t last. They don’t need to. There’s harsh beauty in the noise, and Ramsay knows it. Better still, she finds it. That’s a task not easily accomplished, and Ramsay has repeatedly pulled it off over the course of her career. Each of her previous movies captures human collapse in slow motion. You Were Never Really Here is a breakdown shot in hyperdrive, lean, economic, utterly ruthless and made with fiery craftsmanship. Let this be the language we use to characterize her reputation as one of the best filmmakers working today.

Director: Lynne Ramsay

Writer: Lynne Ramsay; Jonathan Ames (novella)

Starring: Joaquin Phoenix, Ekaterina Samsonov, John Doman, Judith Roberts, Alex Manette, Alessandro Nivola

Release Date: April 6, 2018

Boston-based culture writer Andy Crump has been writing about film and television online since 2009, and has been contributing to Paste since 2013. He also writes words for The Playlist,WBUR’s The ARTery, Slant Magazine, The Hollywood Reporter, Polygon, Thrillist, and Vulture, and is a member of the Online Film Critics Society and the Boston Online Film Critics Association. You can follow him on Twitter and find his collected writing at his personal blog. He is composed of roughly 65% craft beer.