Brandi Carlile Interviews Amy Ray About Her New Solo Album, Holler

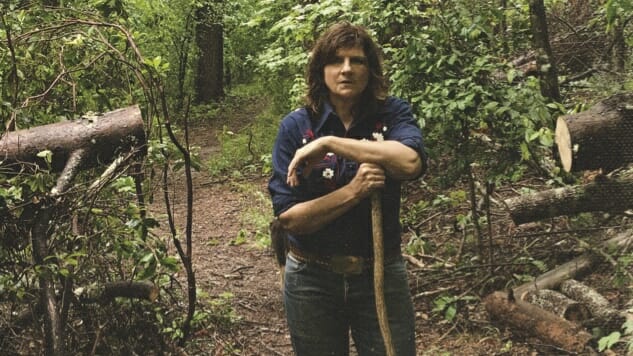

Photo by Carrie Schrader Music Features Amy Ray

Brandi Carlile joined her childhood idols The Indigo Girls on tour the first time back in 2007. That marked the beginning of a friendship and a series of collaborations over the years, so it was no surprise that Amy Ray asked Carlile to sing on her brand new album, Holler, due out this Friday. Ray’s first solo albums explored her love of rock and even punk, but her latest digs into her Southern roots, continuing the country feel of 2014’s Goodnight Tender, with guests who also include Justin Vernon, Vince Gill and Derek Trucks.

There’s an Appalachian feel with horns layered atop traditional bluegrass instruments. And of course her lyrics are as timely as ever. “The songs are all my own compositions and tell stories of late nights, love, addiction, immigration, despair, honkytonks, growing up in the south, touring for decades, being born in the midst of the civil rights movement, and the constant struggle to find balance in the life of a left-wing Southerner who loves Jesus, her homeland and its peoples,” she writes.

We asked Carlile if she’d interview Ray for us about the new record. She came prepared; all I had to do was listen in. What follows is nearly an hour-long conversation with two of roots music’s best singer/songwriters.

Brandi Carlile: Well, Josh, I don’t know if you know this but Amy and I spent some time together last week and I’ve listened to the album a handful of times, but I actually avoided talking to her at all costs so that we could talk about it.

Amy Ray: It was a little awkward.

Carlile: Sorry, Amy, I just didn’t want to waste it, you know?

Ray: No, I’m kidding, totally kidding. It wasn’t awkward, it’s fine.

Carlile: So, I’ve listened to the record now so many times and I have many observations that could be turned to questions, but the first thing that I noticed about it—as a fan of your solo work since Stag—is that this is probably the most sonically thematic record that you’ve ever done, and I was hoping that you could go into how you made this album sound like such a cohesive piece of work. Why—if that was something you set out to do, or if it just happened?

Ray: I think I set out to do that. I mean, you know like with Stag, my very first record, part of the reason it was so crazy was because I recorded it at like, you know, four or five different places and I basically drove around and flew to different people’s studios and kind of walked into their lives—like punk bands that I was influenced by and people that had been on my record label—and kind of, almost like a field recording thing, just gathered takes of songs, so it had a real kind of chaotic musical thread, which was intentional for that record. Ongoing I kind of tried, I had like lyrical themes, but it couldn’t always have musical themes, or sonic like engineering sort of threads, because I had to piece things together and go to different studios. Even for Goodnight Tender I had to do that to a certain degree, although the majority of it was recorded live in one place, it was still a little bit scrappy in some ways.

But for this one, yeah I, and the producer Brian Speiser—I mean, you know Brian—we sat and talked about this record a lot. We didn’t have to talk about musicians as much because I had the band together already, and I had been touring with them for years off and on, so I wasn’t worried about that. So the thing that we worried about the most was that cohesion and like really tried to go for a really specific sound and go into the studio and record to tape live, as we had done with the other records—my previous records, I had done that—but it was very disciplined. We were transferring things at a high sample rate while we were recording, but we only stayed on tape as long as we could. And we didn’t do vocal overdubs to fix things. And we knew the band could do it because we had played together so much. So that was part of it. We left mic placement the same and we had like a couple of stations, like we have one way of recording songs—”Jesus Was a Walking Man”—that was more like being in one room together. We had another way of recording the other songs, and those two situations stayed the same throughout the record sonically—mic placement wise. And vocal mics and all that. We just didn’t change amps very often or we went between upright and electric bass. So it was a very cohesive thing, and then we tried to thread it together with some of these musical interludes. Brian’s kind of dream was to have these interludes.

Carlile: That’s one of my favorite parts of the whole thing.

Ray: So we kind of started that idea a long time ago. They’re tiny moments in the record but you…

Carlile: You want them to be longer though, and then you’re happy that they’re not because it’s like it leaves you wanting more. But they’re really, really incredible, little masterpieces.

Ray: We had some things longer but we had to, to fit on records, just to fit everything in one place, we kind of had to trim here and there. The first piece he kind of wrote it based on like Burt Bacharach, and kind of our love of that vibe almost like a continuation of Goodnight Tender, is kind of that mellow, kind of slow thing. And like leaving off one record and going on to the next—and then crafted into a song. The other interludes are like pieces of songs that I was writing, like one version of a song that I had written that turned into a different version and then another song that was like a lullaby that we didn’t want to put the whole song on the record, so we just used a piece of it and tried to make them turn into each other. So yeah, that like was Brian’s thing.

Carlile: You did them on Come On Now Social with “Sister”, right? I remember, you guys did…

Ray: I forgot that rendition. Yeah, I did.

Carlile: I think it’s really interesting.

Ray: Yeah, I think he wanted the record to feel—he’s very vinyl oriented—so he wanted the record to feel like records, you know?

Carlile: Well I think that’s brilliant. I think about my favorite records—and yours too; we’ve talked about this a lot—are those classic Elton John records that really sound like a place in time. Like the same group of people got together with the same goal in mind in a place in time and made like a really warm, lasting impact and that’s what I feel like this record’s done. So, nailed it.

Ray: [Laughs.]

Carlile: One of the common threads through a lot of the songs that glues them together in one way, aside from like lyrical themes and just this continuation of the sentiment of Goodnight Tender would be the banjos and horns. Are you going to tour with banjos and horns?

Ray: I wish I was going to tour with banjos and horns. Alison Brown plays the banjo on this, and she was kind of a special guest. And she’s a virtuoso.

Carlile: Wow.

Ray: She was my dream to get her for like a whole studio experience. We got her for a few days. She was the one person that we did record with live for most songs that she did, and a few of them we overdubbed because I ended up wanting her on so many things that, we left tape tracks open for her on the songs, and she came in and did it to tape. But we also played live with her. Yeah, so she’ll play off and on as she can, because she’s got her own career and runs a label with her husband and kind of runs like a whole office in Nashville. So, I sent her the dates, and I was like just, “Whatever you can do.” So that’s kind of what we’re working with. The horns and strings, I’ve got a horn section and a string section that I’m going to use in Nashville and Atlanta and hopefully in Asheville. I’ll use the section that played on the record, and I have an L.A. horn section too. I can’t do it the whole time because it’s expensive. We’re in a van, and we can’t fit everybody in the van, either.

Carlile: Yeah, they don’t make vans big enough anymore these days.

Ray: So, I’d have to have a school bus, basically. But we have charts, you know, so as we can, as the tour rolls on, we’re going to try a few cities and people will just drive their own cars between one place and another, and then we’ll see what we can do as the tour continues. But you know, I’m like small. I’m playing in like, honky-tonks, like small places, and sometimes the stage is already not big enough to fit all of us. In Atlanta I play like a theatre, but if I play in Tampa or something, it’s literally a bar where we’re setting up on the floor and there’s people right in my face. So we have to kind of move according to the space, but I can’t wait to play a live show with horns and strings. I think it’s super fun, so we’re going to do it twice. But my band is pretty compact—it’s the six of us—and we travel in a van. We don’t have any crew; we have a trailer. It’s like down to like a science of how we pack everything and who sits in what seat. So Alison will be like the new element, and we’ll figure out what seat she’s going to sit in, and we’ll go from there.

Carlile: Right on. There’s a lot of really brave, I think, interesting, instrumentation on the record—did you play any instruments, or do you play anything outside of what you would normally play on a record? Did you pick up any of that stuff?

Ray: No, I didn’t go outside my box. I wrote a song, “Dadgum Down,” on banjo…

Carlile: That’s one of my favorites, in my top three favorites.

Ray: And then I tried, then I was sitting there with Brian and the band trying to lead them through it on banjo and it was a disaster, so…

Carlile: Yeah, but it’s unique and you can tell that that wasn’t a banjo player that selected that pattern.

Ray: But I didn’t play it though, in the record. I ended up, yeah, I mean I wrote it on banjo, and I wrote the riffs and the way things go on it, but Brian actually said, “Put the banjo down.” And I did. And then Jeff, my guitar player, and Alison kind of worked off everything I had written and just created that same thing from what I had written, but in a more intelligible way. And then Alison, of course, could play all the craziness that she played on a banjo. But I didn’t. For this record my goal was not for myself to experiment instrumentally, but it was to tell other people to experiment instrumentally.

Carlile: That song in particular—which is one of my top three favorites—you can always tell when somebody writes a song on an instrument they don’t normally play because it has that direction that a banjo player wouldn’t go in when they pick up a banjo. It gets to this rock ’n’ roll, throaty kind of thing that happens and then the way that it’s kind of like got that riff that follows the vocal like a Jimi Hendrix song. It’s just really, really unique, and I don’t know, I’m pretty pumped on it. I think you should try and play it live.

Ray: I am going to play it live, but I’m going to have to figure out how to when Alison’s not there. When she’s there I can play the basic rhythm fairly easily, and then she can play all the stuff she plays. I just have to not get in her way. I mean, that’s my goal. With a band—you know how it is because I just saw your show, so you do this too. You try to make everything have a place, and you don’t want everybody playing all over everything all the time.

Carlile: The space of that ghost member that’s probably the most important player in the band.

Ray: Exactly. And I think my banjo playing takes up that ghost space sometimes, so I have to be careful. Because that’s what happens when you don’t really know how to play banjo, you just strum it like a guitar. And that’s fine, but you can’t do that for the whole song, so I have to figure it out. But I have this TEO—I bought this guitar that’s electric that I got on the Indigo Girls last record—and I really, I like the sound of it. And I didn’t think I’d use it on country music, but I handed it to our fiddle player a few times, who’s a really good guitar player too, and it just became another element on this record that we used like three or four times. It kind of brought in, almost like a late ’60s, kind of harpsichord-y vibe that I like that isn’t necessarily in the ilk that we would have thought would work with the stuff we were doing. But it brought a sparkle to some things. One song, I got the bass player to play mandolin instead and my guitar player to play bass because he doesn’t know how to play stand-up bass and I just thought he would do something interesting.

Carlile: I love that.

Ray: Mostly, you know, we move around a little bit. Everyone in my band plays—my guitar player plays dobro, mandolin and stand-up bass. It just isn’t in a very elemental way. My pedal steel player is also a dobro and a guitar player, and my fiddle player is a guitar player. So, I will do that if I hear something. Like, I think on “Oh City Man,” instead of Jeff who normally would have played dobro on a song, acoustic dobro, I had instead my pedal steel player. He’s a different flavor of dobro player and, you know, it’s lucky. It’s just lucky when you have a band that can switch around instruments. That’s kind of one thing that we do a little bit of that we didn’t do on the last record. And then we have Derek Trucks play slide guitar on some things, so we had to leave the space for that, and that was kind of outside our box because he’s just a guest; he doesn’t play with us normally. But for me, my stretching was like just singing in tune and recording live. I mean honestly, trying to really, really capture the song in a way that the phrasing is important, the pitch is important and the texture is really important, of the voice—making sure it’s really landing in the right space. That’s enough for me. If I can get that done, I’m fine. I don’t need to do anything else.

Carlile: My favorite vocal, and I think actually my favorite song, was “Bondsman (Evening in Missouri).” Was that the most vocally challenging song you did, or if not, which was?

Ray: Yeah, it was. I mean, I didn’t have to do it a lot, but I really worked on it a lot leading up to that time. I started writing that song years ago, and I tried it in five different keys. I tried different ways of making it softer or more rock or more this or that. It was actually a song that I was trying to do for the last Indigo record but everybody passed on it, and I think it was because I hadn’t gotten it to the place it needed to be yet. So I just knew I didn’t want to lose that song.

Carlile: No, it’s amazing.

Ray: It’s just a live recording, but it was a cathartic sort of feeling for us as a band, you know? We got to the end of it and we kind of all knew, like, “Okay, that’s the one,” you know? And if there are little things that are out of tune, it’s okay, or when we transfer it to digital if I need to pitch something because if it’s just god awful then I’ll do it. That kind of was my security blanket ultimately. That if it was just terrible, that everything about the performance is so good but one note—you know how it is—that rather than leave that one note in, I knew I could fix it. I would be able to move on from that and not like be burned by it and have to do it a hundred times. But I didn’t end up doing that that often because I let a lot of things go, pitch wise, that maybe I would have fixed if Emily was trying to sing harmony with me, you know? That kind of thing. But when it’s one lead vocal and you don’t have to worry about someone singing with you and frustrating them because it’s not in tune…

Carlile: I didn’t anything that stood out to me pitch wise, at all.

Ray: Now, I can listen to it and be like, “Okay, cool.”

Carlile: I heard a lot of spoken-ness and storytelling. I’ve been saying this since the Cover Stories project when you guys did “Cannonball” so amazingly. It’s one of my favorite songs on that record, and sometimes it is my favorite song, but where, I think that Randy Newman is such an amazing spoken/vocal storyteller person. Sometimes you have a lot of that depth on this record where you know, you definitely did your own version of it but it makes you listen. It’s not a record that you’re going to put on passively at a dinner party, they’re going to want to hear what you’re saying.

Ray: Well, I mean Randy Newman is a genius. I wouldn’t put myself in his realm, but I would definitely say, I consider one of the strong parts of the country music that I like, and the Americana music I like, and folk, well and everything—it’s all writers—is when they can tell a story that they’re part of but they’re not. It’s their lens but it’s maybe someone else’s perspective too. I worked on that in these songs. There’s a lot of stuff that’s not necessarily—it’s not all me. It’s like, neighbors or experiences that I had but also morphed it with someone else’s experience and kind of created a new experience out of it, like stories.

Carlile: Yeah, I can hear a lot of that observation writing, especially on “Sure Feels Good Anyway.” You’re writing about the South and probably people you know, and it definitely resonates. It’s super beautiful. I don’t usually like to bother somebody and ask them what a song is about, so I wont. I’ll just tell you that I love the metaphor of “Fine With The Dark.” So, why are you fine with the dark?

Ray: I’m fine with the dark because I think darkness is important, and I think metaphorically we too often associate negativity with the color black, and racism and everything. I think that the metaphor of darkness and light is used by everybody. It’s used in African American literature, it’s used in white literature, it’s used in Hispanic literature, it’s used in all literature—but there is a point where it can start being used where darkness is always invoked in a negative way. I am quite moved by Nina Simone and some of the writers of that era and singers of that era, black singers and black writers, who would point out in a sort of a tricky way that black was beautiful, and it needed to be said at the time.

So I was listening to “Black Is The Color Of My True Love’s Hair,” actually, and thinking about how subversive that song was when she sang it. That’s like one of my favorite songs of all time, of any song ever, and I can listen to it a million times over. Her way of singing it. So I just started thinking about that song when I was writing about how we’re taught there’s these definite metaphors for light and dark. And I mean, we do it ourselves in Indigo Girls, too. I try not to do it, now, but it’s done in our past. I was thinking about that, and I was just thinking about how one of the most beautiful moments of my life ever was when I experienced a black out in New York City and like how incredible it was to be able to see stars, and that sometimes I’m so tired that all I want is to be in dark. I think about field laborers and people who are baking in the sun, and their friend was when the sun went down. I was thinking about all that when I wrote it, and I had been listening to not just Nina Simone but Elizabeth Cotton, who is just one of my favorite African American guitar players. I was thinking about her and her style—it’s impossible to cop—but I was trying to learn how to do finger-picking that way and listened to her on a plane ride where I just left that—it’s like a greatest hits sort of collection of her stuff that I have on my iPod, it’s like a playlist, and it was running and running and running and I got back to my house and I was just like, “Alright, let’s try to play that way.” This is the song that came out of it, basically. Learning how to play like that, I can’t really do it yet, but the song that came out was kind of like when I was trying to learn how to play banjo, it ended up being a song that I liked and I can’t totally execute it. I mean, I play it live on the record but it’s not everything I want it to be. It’s almost fragile. I tried to get better and better at it, but Brian was like, “I want you to record this before you get too good at what you’re doing because I want that fragileness.” I was like, “Easy for you to say, you don’t have to suck on the record.”

Carlile: It’s a really complex little thing.

Ray: It’s like chords, but what I’m trying to do is, for me, it’s not my normal thing. So that’s something that I’ve been trying to learn how to do, just ever since I heard Elizabeth Cotton. I was like, “Oh man, I want to learn how to play like that.” That’s where that came from.

Carlile: That’s a brilliant song, and that’s an incredible answer, honestly. Really great answer. A question that I’ve asked you lots of times—I think probably everybody asks you every time you put out a solo record, but I think Indigo Girls fans read Paste, and I think people would love to hear you answer it—how do you differentiate between an Indigo Girls song and an Amy Ray solo project song?

Ray: It’s really like, for me, about collaborators and who I hear when I’m writing the song. I hear Emily, in my head, and it’s an Indigo Girls song. That’s really what makes it for me. If it’s a straight-up, like a super country song, she could sing and play on anything, I know that. But I hear something about her, and I try not to keep it in a box like, “Oh, we only do this in Indigo Girls.” So I try to make it, not like, this is a punk song so I need to do it when I make a punk record or this is this kind of song so I need to do it—it’s a pop-folk song so it has to be Indigo Girls. It’s more like, do I hear this as something that’s like a duo, like harmonic, in the harmony realm and where I have left all this space for her to play guitar in a different tuning. When I hear all that going on while I’m writing, then I know it’s an Indigo Girls song. Now, I’ve played with my band for so long, with my solo band, the country band specifically, that if I hear them, then I know it’s that song. Sometimes, I’ll hear who I want to sing on it.

Carlile: Both Vince and I are on record as noticeably religious artists in our own right. I know you didn’t want to use that term, but, you know, it applies. So when I first got “Sparrow’s Boogie,” I thought that maybe you were kind of bringing us together on that song for that reason until I heard how many references there were to specifically the Christian faith on your album. Was that a conscientious thing or were you just using all those great Biblical metaphors?

Ray: I don’t even think about. And I definitely wasn’t thinking of you and Vince. I don’t even think of y’all—like it doesn’t even occur to me, in my first thought of y’all. My first thought of y’all is your vocal prowess and talent. So that’s my first thought. And then, for you, because I know you, and I knew you’d understand what I was saying in the song, and probably even understand where it came from for me, emotionally. And that was important for me. I didn’t think Vince would, but it didn’t’ matter, as long as I had your emotion in there as that piece it would work for me. And I didn’t even think about Vince as being religious, until someone was like, “Oh, you know, remember him and Amy Grant are together.” And I was like “Oh my god, I totally forgot they were even together.” And I’m such a huge Amy Grant fan that I was even more into it.

When I write—for me, this style of music always plays into when I’m writing more gospel songs—it’s something that comes out of me supernaturally. I don’t ever think about it. It’s almost like, I have to keep myself from doing it too much, I think, because I was raised going to church four days a week, and then I went to church camp all the time, and I think I’m just naturally a worship leader, I mean, a music worship fan. I cant’ help it. I think, for me, Jesus is like a vehicle for me, of a person that I look at as an activist.

Carlile: Yeah, you write about him like he’s a socialist renegade. I always really liked that about your perspective.

Ray: And that’s how I think about him. And when I was growing up that’s how I thought about him. I’m as much pagan as I am anything else. But Jesus is a fixture of my life. It’s like my cultural construct, like my Joseph Campbell, you know—everybody has this thing, this myth that they need to help them in life. I don’t think Jesus is a myth, but it’s like—I think turning water into wine is a metaphor. I don’t think it’s a miracle. But it could be, who knows. Crazy things happen. I don’t think we know, but what we do know is that faith is not based on those things. It’s based on all of these mysterious ideas and things that we cling to that help us get through life and help us have a moral compass and help us figure out shit that we’re trying to figure out and solve problems.

For me, Jesus is one of those things. It could have been Mother Theresa, you know? Depending on how I was brought up. But I was brought up with Jesus. And I live in an area where that’s still a strong reference point, unfortunately the only one most of the time. So it comes out in my songs most of the time.

But you know what I mean. We talk about religion a lot, so I know that you understand what I’m saying. But I think that spirituality and our tradition can be infused in our songs, and you hope that people can not be alienated by it, but be able to carry that into some other form that they can use with their life.

Listen to Amy Ray’s 2012 Daytrotter session in Asheville, N.C.:

Carlile: I think that one of the few areas where, as LGBTQ artists we’re privileged, is that we can sing about religion from a perspective of persecution and have it land on the human ear that really does translate as compassion and sacrifice. Because it’s not something that’s justified on privilege; it’s the opposite. So it has weight, I think, when we talk about it, that’s different than when people that have been justified by that faith talk about it. Because we’ve been persecuted by the faith. It’s a different message, and I think it’s really really cool, when it comes from someone like you. Even if it’s just metaphor, or even if you’re trying to shine a different light on the way we interpret Jesus. People have done that before, who are amazing: John Prine, Kris Kristofferson. They sing about Jesus in the same context— he’s more of a game-changer socialist renegade than he is a justifier of the religious right. But it’s different with them because they’re white men, and they’re justified by the common perspective of the faith. And I think it’s really special when you talk about it that way.

Ray: Well, I agree that Jesus is a strong tradition in American songwriters, and maybe Canadian songwriters. And I feel like, yeah, when there’s a certain otherness about who you are, you can bring out that in a different way. So as a queer, I can bring it up in a way that might be slightly different because of my experience in the church. I think that’s an undercurrent that’s subversive. But the main current is that, well, you know, we’re in a time when the religious right is trying to talk about what’s right to do, but a lot of the time they’re not doing the right things. But I have to say, one thing that I know about a lot of Evangelists in the immigration moment, is that some really hardcore Evangelists are very pro-immigration, which is really interesting. Like Mormons. They believe in keeping families together. There’s a weird split within that community itself. I didn’t think about that when I wrote that song, but there is. I think it’s the posers, you know. They’re using this as a tool, but its’ not really accurate. They’re using Biblical references, and you’re like, “This is crazy!”

Carlile: You’re like “that’s weirdly out of context.”

Ray: Yeah, and it’s so opposed to what the Christian tradition was supposed to be about. But I think the otherness thing—it’s just part of my life. You struggle with the church as a gay person, to try to stay in it and still use all the good things in your life, and leave out the bad.

Carlile: Yeah. Well when you hear a person sing about it, that’s also privileged by it, you bristle at the terminology. At the buzzwords. And you hear you sing about it, you don’t bristle. You listen and you maybe rethink a couple things. And I like that a lot. Just wanted to tell you that.

Ray: [Laughs.] Yeah.

Carlile: I have another question for you. I know we’ve been talking for probably too long, but I wanted to ask you one outside of your record question, because I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. Women in music—I don’t know if you’re hip to that Instagram “Book More Women”https://www.instagram.com/bookmorewomen/. Have you seen it?

Ray: No.

Carlile: It’s amazing. So it’s this Instagram page specifically dedicated to posting posters from festivals in the U.S. where they take all the men’s names off the poster just leave the women’s names. They basically expose that it’s just a bunch of blank pages.

Ray: [Laughs.] That’s funny.

Carlile: And it looks so shocking! So startling. You know, the big festivals that you just kind of blindly accept, places like Coachella or even Bumbershoot this year. And I’m wondering this: I feel like we’re trying to address this issue from across the board, from all aspects of employment, from corporate all the way down to public service, music, the arts. I feel like music in particular is a sensitive one. I think it’s underrepresentation for women in a big way. And because I think that it’s really specifically bad right now, I’m wondering what you think about the progression of women in music from the ’90s. Is it worse or is it better?

Ray: Whew. Well, one thing I’ll say is that I really see your intentional movement behind this. You know, with the festival in Mexico at the end of January, the Girls Just Wanna Have Fun weekend, and the selection of artist you have. I can see the intention behind that with all the women and trying to include diversity. Stuff that’s important when you’re putting festivals together. And I think women are at least more conscious about that now, especially in these times.

I think during Lilith Fair it was a little harder. The diversity issue was a little bit harder because they were struggling with promoters and their attitudes. Everything is important. I think what you’ve discovered over time is that it’s not just who you have on the bill. It’s who has access to the information to come. And where those tickets are being sold, and if the venue is somewhere where people can get to. So with Lilith Fair, it was always easier to generalize, but there were often very big white audiences, and it was in venues that were not well served by public transportation. It was not as popular with groups that might’ve come because it was not in their mind. Like, “Oh I know that venue because I’ve seen blah blah blah there” So if Missy Elliot played, it wouldn’t be at a venue where she’d played before, or at a place where people would normally go to see hip-hop shows.

Carlile: Like when you were at Lilith Fair, Erykah Badu was on the Gorge, and I was totally blown away, but that occurred to me, too.

Ray: I mean, at that time, it was very hard to figure all that out. And I’ll give them credit, because I know they were trying too. But one thing that does happen in those festivals is that the diverse part of the bill, the people of color or, at the time, gay people—they’re put as early in the day as possible.

But you have to be so intentional when you want to put something like this together. And it almost feels intentional to the point of being patronizing at times. And so it’s hard. But I think a lot of progress has been made in communities of women, because we’ve thought about it so much. And in communities of color they’ve thought about it. And there’s been attempts to cross-pollinate, there’s been attempts to have our own festivals, to try to build up our own infrastructure.

And I think a lot of women feel that, and I think there’s been a lot of progress. But I think we’re still fighting the same gate-keepers we were fighting back then. Which is, there’s a lot of people in charge who are upperclass white men. Privileged. And they’re still the majority of people in charge. If those are the gatekeepers still, then that’s what’s gonna happen.

I think it’s changing, though. I think generationally it’s changing. Record labels aren’t as important anymore. What’s important now is distribution networks, and the media, and internet and festivals. Ways of getting your music out there. A lot of those are—I think women are starting to move into those ranks. I think we’re trying to develop women as sound people and guitar techs and as tour managers. Producers, engineers.

So I think we’e made some progress, but it’s not even close to being enough. I think it goes for a while where we’ll have a great number of incredible artists who get recognized as women. It might be folk or country, it might be hip-hop or pop music. But it’s always considered a trend. It’s never the norm. So until it’s considered standard for what we’re doing, there will always be backlash against it. As soon as something is a “trend,” a backlash starts. I think that’s what we have to work on: How does this become the norm?

We’re moving there, it just takes a lot of effort on everybody’s part. I’m always hopeful. I’m an idealist. If I see so many people doing so many good things—and for your generation, it’s a no-brainer. And for artists who are even younger, their capacity to organize and the way that they look at things is so incredible.

Watch the Indigo Girls perform in Mountain View, Cal., in 1994:

Carlile: It’s so important that they take it on at their level. You talk about Lilith Fair or even something as isolated as what we’re doing in Mexico. That’s a start, and it’s great in our niche area that we’re willing to do it. But if everybody did it in their niche area from the club area all the way up to theaters and then festivals and arenas and things like that then that’s what it will take. I don’t think I told you about this, but I was booked on a small tour to open for a rock ’n’ roll band that you and I adore. We love them. And I was so excited about it, I was all ready to go, and a few months before the dates were announced, I got a call that three or four of the venues wouldn’t allow me to open. They wanted me to play first of three.

Ray: Are you serious?

Carlile: Yeah, they blatantly said that it would be better with a male, more guitar-fronted act.

Ray: Oh my god.

Carlile: Yeah. And I know the singer of the band really well. And I never told him that, and if I did tell him I think he would just die. But that was the first time I realized that it might actually be getting worse. Because of the fact that streaming has usurped our industry in such a big way, and because there’s fewer opportunities for what I call “pipeline men” to make money between the art and the delivery of the art, that touring has gotten so seized upon and so curated by mainly men. That I can at least remember being a teenager when I became infatuated with the Indigo Girls when I saw you at the Showbox, when I saw everybody coming together—Team Dresch, the whole Riot Grrl movement, from Lilith Fair, from everyone from Paula Cole to Shawn Colvin to Dar Williams—you could find women’s music everywhere. And you could find double bills of women crushing shows all over the country. I felt like I could find women’s music easily. And the only way I could go to a concert was if there was adequate female representation or my parents wouldn’t let me go. One of the reasons was that they just wanted me to be safe. When you see Coachella doing these studies, they’re coming out with a 100% rate of reported sexual harassment and aggression at a lot of these festivals, I think we have a real problem where we should be addressing having adequate mirroring and representation at all levels of concerts and music. Because we take music away from people as a catharsis, I think we’ll be in real trouble.

Ray: That’s so interesting. And I think your analysis is right on. I think touring is the major way of making money right now because record sales don’t. I mean for us, for Indigo Girls, we wouldn’t let anybody tell us that. I mean, I don’t think you should that artist you were talking about off the hook. And I don’t mean that in a mean way. I just think that if they don’t know what’s going on at the top of their orientation and with their agency and with their promoters, they need to know. Because they have the power to change that. Because if you have the power, and you do, on your level, you have the power to pick who opens for you, and you’re very intentional about it, and you do it.

Carlile: Yeah, if somebody didn’t tell me I would be pissed.

Ray: And you have the power to do it. Even if a promoter says to me “I don’t think this is going to work with this bill,” then I say “why not?” And if they give me a stupid answer, I tell them that’s ridiculous, and if they give me an answer that makes sense, I say “Alright, we’ll pick someone else,” and then I’ll pick another woman. [Laughs.]

Carlile: That’s why I love you.

Ray: But we don’t always pick women. We pick artists who we think are important artists who fill this thing that we think is important. Like, I’m going on tour with my band, and it’s all guys. It’s a country thing, whatever. But that’s my band. But all my openers will be women, because that’s the way it needs to be. We need to have more women there. But the guys need to be thinking that way too! The rock bands who have all this power, they need to make decision that include this in the power they have. They need to hold these festivals accountable. If somebody huge is playing Coachella, they can help by saying “We need these things to happen at this festival,” and they can sign petitions and get other bands on board to shift that.

It’s also about leadership. You have to have more women who are producing and leading these. Because the more women you have involved behind the scenes, the more likely it is that those kinds of decision will be made in the right way. Maybe not always, but it’s likely.

Watch Brandi Carlile at the Paste Studio in Atlanta in 2010:

Carlile: Furthermore, this isn’t a sacrifice. There are women who are intentionally staying home and not buying that ticket, spending that money. And as an industry we can get their money and their ticket if we just provide them with adequate representation.

Ray: It’s hard to figure out what makes an economic difference to these promoters. Like, what hits them hard enough in their pocketbooks to get them to change their ways? I think one thing that’s a serious wake-up call is the #MeToo movement, and what’s happening at their festivals and how they can change that. Enough of a PR thing around that that they just have to look at themselves and ask what they’re doing. They have daughters or sisters or mothers, you know?

Carlile: Well, on a good note, Newport is 50/50. And Bottle Rock is 85/15

Ray: Wow. That’s great! Indigos don’t really do a lot of these music festivals, it’s not really a part of our world right now. Sometimes I feel like I don’t know what’s going on, so I’ll go online and look at all these lineups for that reason particularly, just to see about women and what’s happening in that regard. Not because I want to play, but as an activist in our world. It matters.

Carlile: Well I love your record. I think its absolutely amazing, I’m gonna keep listening to it every single day, you know me.

Ray: I loved yours too! I didn’t even get to ask you questions about yours.

Carlile: I already talked about mine too much. [Laughs]

Josh Jackson: Well guys, that was such a pleasure and an honor to get to listen in. I think that gives a wonderful perspective on this record and your relationship. The last thing I would love to have you say something about is: This is not the first time you guys have collaborated. Why do you keep coming back to work together?

Carlile: Well, for me, the Indigo Girls have been heroes of mine since I was about 14. I covered all their songs, which is how I learned to play guitar. I went to all their concerts I could possibly go to. I stood in line all day long. When Amy came out with Stag, I was actually blown away. I covered “Measure of Me” and I became a fan of the Butchies, and I stood in line and watched her at the Showbox. I’ve been a fan for most of my human life. So any opportunity I can get to collaborate with Amy is a blessing in my life. And I remain a fan, and I think that, if it’s even possible, you just get better and better and more and more profound as an artist and a songwriter.

Ray: I feel the same way for you as a songwriter and an artist. I also feel like, as an organizer and a business person, I really pay attention to how you do things, and it’s a template for me sometimes. You’re like a mentor. Because I think mentoring is not a generational thing. It goes both ways. And I remember the first time you walked into our lives and we started singing together, it was like a freakin’ earthquake. And it changed us. It infused me and Emily with this energy that we really needed at the time. We were just floundering a bit in some way. And then you came in and we were singing together all the time. On an emotional level and a spiritual level and a musical level, it gave Emily and I a collaborator who was just so exciting. And somebody we could believe in, that we could play with and look at as a mentor. Someone who was fresh and younger and had a different perspective—one that you didn’t often get to see or hear about. Someone who was willing to pour 100% energy into what you’re doing, musically but also business-wise. And that’s really important to us. So for us, it’s been great watching you develop, and we always take note of how your’re doing things and what’s going on in your life.

Carlile: Really? That’s so amazing to hear.

Ray: Well it’s true. I’m not making it up. For me, I’m always like “I gotta make sure I see Brandi’s show this tour.” And I’ll look at your website to figure out what you’re doing and how you’re approaching things. And I do this as a fan, but also as a person who can learn from it, as a student. Any chance I get to cross paths and talk in a personal way, but also in a business way, is super important to me. I need allies. Everybody needs them—men, women, doesn’t matter what you are, you need allies in this business. People you can go to sometimes and say, “ugh, I have this situation and I don’t know how to handle it”

Carlile: Oh yeah. How many times have I called you with one of those?

Ray: Well, I’ve called you as many.

Carlile: We should’ve warned Josh about how long you and I can talk for.

Ray: He can go do something else for a while. [Laughs.]

Jackson: I’m enjoying every minute.

Ray: Thanks Josh, we appreciate it.

Jackson: Thank you guys, I so appreciate all the music you’ve both given us over the years. And Amy, Holler is a fantastic record. I’m really enjoying it.

Ray: Thank you. And I appreciate Paste so much because, generally speaking, you guys have held that torch that needed to be held for a long time.

Carlile: Oh it’s a fucking island isn’t it. It’s absolutely incredible. Beacon of light.

Jackson: Well thank you both. That means a lot.

Amy Ray’s new album ‘Holler’ debuts Sept. 28.