Guy Clark’s favorite place was the basement of his West Nashville home, where he painstakingly hand-built flamenco guitars and hand-built songs with the same exacting sense of craftsmanship. It was there that Clark, who died Tuesday after a 10-year-bout with lymphoma at age 74, honed songs as unforgettable as “Dublin Blues,” “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” “Homegrown Tomatoes,” “She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” “Randall Knife” and “L.A. Freeway.”

But Clark was never foolish enough to claim—as so many self-deluding pop stars do—that the songs are out there in the ether waiting to be captured by the right antenna. Those pop stars failed, he knew, to recognize the sudden appearance of inspiration as the prompting of their own subconscious. And by pretending that the songs arrived already finished, those lazy pop stars rationalized their unwillingness to do the work of crafting an inspiration into a finished song.

Clark was a lot of things, but lazy was not one of them. His basement was set up so he could work on songs with a guitar, notepad and tape recorder until he got stuck. Then he would put those tools aside and turn to the saws and vises of the luthier trade. While he worked on building a new guitar, the new song would be bubbling in his subconscious. When a new idea broke through to the surface, he would pick up the notepad and guitar again to take the next step in writing a song. All along there was an unending series of hand-rolled cigarettes, some containing tobacco. I spent a handful of happy afternoons in that basement, and my favorite story from those days concerned the song “Better Days.”

“I work on songs all the time,” he told me. “I still work on songs that were written 20 years ago. If there’s a line that I never liked, and all of a sudden a better line pops out of my mouth on stage, I’ll use the new line forever after. For example, one of my favorite songs is ‘Better Days,’ but there was a line that never suited me. I tried to change it but I couldn’t think of a better one, so I went ahead and recorded the song as it was.

“Years later I was down in Australia where I met a woman who said she used ‘Better Days’ as a theme song for the battered women in the shelter she ran. I told her I had stopped playing that song because I didn’t like this one line that went, ‘See the wings unfolding that weren’t there just before/On a ray of sunshine she dances out the door.’ I always thought that was really lightweight. She said, ‘Yeah, the women don’t like that line either.’ So I said, ‘Well, what about this,’ and I changed it to, ‘See the wings unfolding that weren’t there just before/ She has no fear of flying and now she’s out the door.’ And I’ve sung it that way ever since.”

The original version was the title track of Clark’s 1983 album, the last part of a trilogy he did for Warner Bros. Records. All three LPs were later released as a two-CD set on Philo, Craftsman. That word defined both his process and his achievement better than any other. The revised version of “Better Days” can be heard on 1997’s Keepers—A Live Recording.

“Keepers” was Clark’s phrase for songs that are worth recording. Like a fisherman, he implies, you hook and reel in a lot of songs from the subconscious but most of them are too scrawny and ill-shapen to take home. So you throw them back into the pond with instructions to eat a lot of plankton and fill out. He learned that—and so much else—from his best friend and greatest influence: Townes Van Zandt.

They met in 1963, the 21-year-old Clark was a college dropout who dabbled in building boats and playing folk music in Houston. Van Zandt was 19 at the time, a scrawny, laconic dark-haired kid with a dry wit. When Clark first met him, Van Zandt had only written two songs, “I’ll Be Here in the Morning” and “Turnstyled, Junkpiled,” but they were enough to give Clark a whole new perspective on songwriting. He had always assumed that folk songs were so old that no one could remember writing them and that pop songs were so silly that no one gave much thought to writing them.

“The first time I heard Townes, I went, ‘Wow!’” Clark remembered. “Here was someone who was writing new songs that weren’t talking about girls and beer in moon-June rhymes. There was something intelligent about the way he used the English language. I said to myself, ‘Here’s a reason to write a song.’ I started writing the day I met him.

“It wasn’t like you could match Townes or even imitate him,” Clark added, “but you could try to use the English language like that. When you hear a good song by Townes or Dylan or Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, it makes you want to write a song—not like them but as good as them. Townes and I would play songs for each other all the time—not like it was a competition but because we wanted each other’s approval. If he didn’t like it, he wouldn’t say anything, but sometimes he’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s good.’ Who wouldn’t want to hear that from Townes?”

Clark was divorced and working as an art director at the CBS station in Houston when he met his future wife Susanna at the end of 1969. She told him, “Look, if you’re going to be a songwriter, be a songwriter. Don’t dabble at it and then spend the rest of your life wondering what might have been.” With that challenge ringing in his ears, Guy moved to L.A. and brought Susanna with him.

“We were living in this garage apartment in this straight neighborhood in Long Beach,” Clark explained. “We woke up one morning to the sound of the landlord chopping down this beautiful grapefruit tree, and my first reaction was, ‘Pack up all the dishes.’ It sounded like a line in a song, so I wrote it down. Just about the only discipline I have as a songwriter is to write down an idea as soon as I have it. You wind up with a stack of bar napkins, and the real work comes the next day or week when you sit down and go through them to see if any of them makes any sense.

“I played in a little string band while I was in L.A., and one night we were driving back from a gig in Mission Beach at four in the morning and I was dozing off. I lifted my head up in this old Cadillac, looked out the window and said, ‘If I can just get off of this L.A. Freeway without getting killed or caught.’ As soon as I said it, I borrowed Susanna’s eyebrow pencil from her purse and wrote the line down on a burger wrapper. If I hadn’t, I might not have that song today. It was a year later, when we had moved to Nashville, that I was cleaning out my wallet and I found that scrap of paper. I put it together with ‘Pack up all the dishes’ and this guitar lick I had, and it all became ‘L.A. Freeway.’”

The Clarks had moved to Nashville in 1971 because Guy had finally landed a publishing deal with RCA. Soon he and Susanna were newlyweds with the irascible Van Zandt as a house guest. The parties at the house became legendary as the likes of Emmylou Harris, Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, David Olney, Jerry Jeff Walker, Mickey Newbury and Vince Gill would pass around a jug of wine and take turns singing their latest songs. No one knew who they were at the time, but they were getting the best training a songwriter could hope for. And it paid off in the long run, for this crowd supplied country radio with its best songs of the 1980s.

“None of us had any money,” Clark said. “Townes was making records but he was barely getting by on college gigs. We were always wondering if we could afford a jar of mayonnaise. But that was our job—to hang out, get drunk and play songs that no one had heard before.”

Clark’s songs were soon at the top of the country charts: “She’s Crazy for Leavin’” (Rodney Crowell), “Heartbroke” (Ricky Skaggs), “New Cut Road” (Bobby Bare) and “Oklahoma Borderline” (Vince Gill). Clark also had songs recorded by Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Lyle Lovett, Waylon Jennings, George Strait, Tom Waits, Patty Loveless, Nanci Griffith, Rosanne Cash, Brad Paisley, Alan Jackson, Kenny Chesney, Joe Ely, Emmylou Harris and Townes Van Zandt.

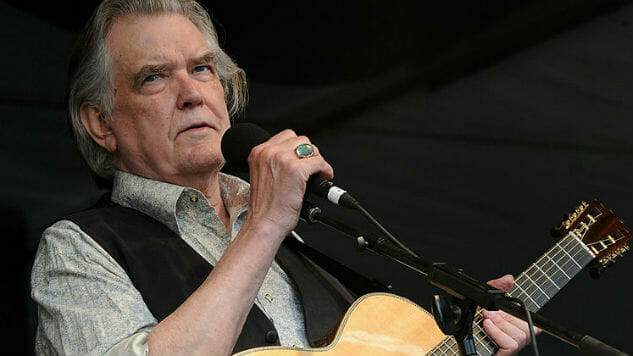

Van Zandt died in 1997, Susanna in 2012. Guy Clark released his last major-label album in 1995, but he enjoyed a rewarding second career as a well-respected songwriter who more-famous singers were eager to interpret and/or co-write with. The swept-back dark hair above his high cheekbones that had once made him look like a rodeo star had turned silver, making him look more like a Civil War senator. For as long as he stayed healthy, Clark continued to tour, performing from one of the greatest song catalogs of his generation, most often with his other best friend, Verlon Thompson.

For all his success in Nashville and in the country field, Clark never thought of himself as a country artist. He always thought of himself as a folk-blues artist in the tradition of Van Zandt and Bob Dylan. In his mind, he wasn’t writing for country radio, he was writing—and constantly re-writing—to get that sought-after nod from Van Zandt. On the other hand, he came from a small town in West Texas, and he could never escape those roots.

“There’s not a lot of country music that I like or that I’ve ever liked,” he told me, “and Leadbelly and Lightnin’ Hopkins influenced me more than Hank Williams or Lefty Frizzell. But I’m from Monahans, Texas, and when I open my mouth, it comes out sounding country. If I’m going to be true to myself, it’s going to sound country.”