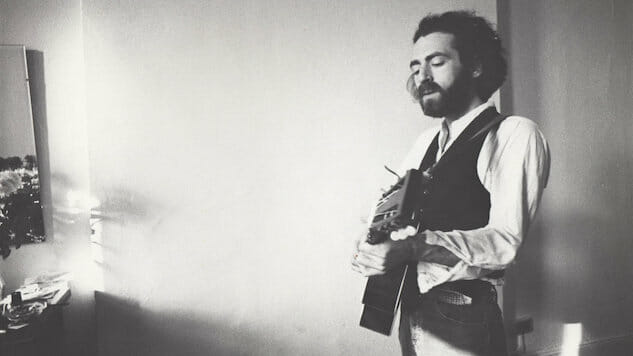

The Times Catch Up With Jay Bolotin

An unheralded Nashville songwriter from the '70s is finally getting his due.

Music Features Jay Bolotin

Our story begins at a dodgy amusement park outside Cincinnati on a hot day in 1986. It’s there that we find our hero, a ragged visual artist struggling to make ends meet, sitting on a crate, trying not to throw up in front of his two young children after being jostled around on the teacup ride.

As he breathes deeply and fights back the nausea, he hears a song in the air, tinnily spilling from a pair of speakers attached to a wooden pole nearby. It sounds familiar. Very familiar. A small ripple runs up his spine when it dawns on him, “I…I think I wrote that song.” He says that out loud to his kids, “That music…I wrote that music.”

“And they said, ‘Can we go on the ferris wheel?’”

The song was Dan Fogelberg’s version of “Go Down Easy,” released on his 1985 album High Country Snows. But when our hero, Jay Bolotin, wrote and recorded it, the tune was called “It’s Hard To Go Down Easy,” a devastatingly pure elegy to a woman picking up the pieces from a broken relationship. “She learned to cook the meals,” Fogelberg sings with a quaver over a finger picked acoustic guitar figure and the pleasant shuffle of a snare drum, “and she learned to start the fire…she sits down to the table/with friends and several others/and she tries real hard to never be alone.”

The song was originally captured at a demo session he did in 1972 in Nashville. It was one of many demo sessions that Bolotin did during his time in Music City, which yielded a couple of small successes, like David Allen Coe giving a light psychedelic dusting to Bolotin’s “Canteen of Water” for his album Tattoo.

Fogelberg recording “Go Down Easy” felt much different. Not just that he had smoothed out all the rough edges with his dulcet voice and adult contemporary leanings, but also because it was a minor hit. Enough of a success that its writer could stumble upon it in an amusement park in Middletown, Ohio.

When Bolotin got home, he made a call to Owsley Mainer, an old friend who gave the budding singer/songwriter his first Nashville gigs at the Exit/In, the famed venue where future talents like John Hiatt and Mickey Newbury got their starts. “I think somebody released a song of mine,” he told Mainer. A few days later, someone in Los Angeles called up, saying “We’ve been looking for you. We have a check for you.”

“I thought it would be, you know, like $12 or something,” Bolotin recalls with some hesitancy. “But if you add several zeroes to that… It was astounding. That one really did make a difference for myself and my children so that’s wonderful.”

That’s what life is like for the huddled masses that don’t have the luxury of hit singles or sold out concert dates. It’s the little victories that help the drudgery and downturns feel that much more manageable. Bolotin’s career has been marked by such moments. These days that involves his visual art, the sculptures and woodblock prints and avant garde films that he makes. A gallery or dealer will snap up a piece every now and again, or he will pre-sell work to a few collectors (“They’ll pay me half up front and half on delivery”). That’s how he survives.

But over the past few years, interest has flared up again in his career as a writer of songs that are, like the best country and folk tunes, plainspoken, unhurried and easy to connect with on a visceral, bone deep level. “Dear Father,” a Leonard Cohen-like heartbreaker about the troubled relationship between a son and his dad that Bolotin recorded for his sole studio album, popped up on Numero Group’s 2009 compilation Wayfaring Strangers: Lonesome Heroes. And earlier this year, the archival label Delmore Recording Society dusted off his Nashville demos for a collection released as No One Seems To Notice That It’s Raining.

Those flickers of joy and sustaining successes pop up throughout Bolotin’s life and work. “Your lovers seem to come when all is going right,” he sings on “Don’t Worry About Winning What You’ve Already Won,” “And leave you at the first sign of something wrong/Like a worker who is welcome when the grain is up/And shunned when the stubble’s on the ground.” For Bolotin, it often feels like he followed a carrot on a stick, straining to reach some next level that he was never welcomed into.

At least that’s the tone of the letters that are reprinted in booklet that comes up with each copy of Raining. The excerpts begin in 1972, not long after Bolotin’s arrival in Nashville. By that point, he had left his home in Kentucky and spent a short period of time studying at the Rhode Island School of Design. But he was drawn to the world of songwriting through the coffee houses and bars in Providence, earning enough respect to land a contract with Commonwealth United Records. He recorded his self-titled album, it was released and the label folded three weeks later. After a stretch living for a time at an abandoned camp in New Hampshire and back home in Kentucky, he decamped to Nashville where he found a welcome home at the Exit/In.

“It seems here in Nashville that the people who appreciate my music the most are other musicians,” he writes in a letter dated October 14, 1972. “If someone ‘famous’ gets up and tells [the audience] what they are about to hear is good then I guess they figure it must be – so they clap louder.”

“It was pretty lowkey in the beginning,” Bolotin says, speaking recently from his home in Cincinnati. “You know, you’d go to the bathroom and standing right next to you at the urinals would be John Hartford or somebody like that. That’s just the way it was. That was more to my liking at the time.”

Bolotin’s regular gigs at the Exit/In generated a healthy amount of buzz. Enough to land him a small publishing deal at $50 a week and spots on bigger concert bills. He would record demos and have proper recording dates, like playing dulcimer for Joan Baez. And folks like Kris Kristofferson would be on the phone, singing his praises and offering to work with Bolotin. But as is more often the case as the gatekeepers in Nashville would care to admit, it all added up to not very much at all. As well, the longer Bolotin stayed in the city, the more disillusioned he became with the way things were handled there.

For example, a manager named Bert Bogash decided to take Bolotin under his wing and help draw some attention to the songwriter’s work. Bogash convinced famed producer Norbert Putnam to stop by the Exit/In. But when another songwriter on the bill got wind of the guest in the audience, he forced his way to the front of the line.

“I was walking up to the stage, and he got in front of me all red in the face and pronounced that he was playing,” Bolotin remembers. “It looked like it was going to come to fisticuffs. I said, ‘Well, go ahead then.’ Norbert left and [Bogash] was so mad at me. He said, ‘You have to learn how to exist in this business!’ I said, ‘Bert, if I have to find somebody to get up on stage to play my songs, that’s totally against what I write songs about.’”

From there, it was a long slow fade out. Bolotin would get signed to another publishing deal at Kristofferson’s behest but that fizzled out. Coe’s insistence that his next album would feature a full side of Bolotin’s tunes became a single song. He would eventually leave Nashville for Kentucky but would bounce back there for gigs and to spend time with friends. But as the door would creep open a little for him (a spot opening for Coe in Chicago, playing songs for Buffy Sainte Marie, Putnam insisting that they’ll work together soon), it would quickly get slammed shut again. As he put it in a 1975 letter, written after a gig with Newbury in Nashville, “There were people there who hate both me and my music. It seems that when someone dislikes me or my music – they dislike with a real vehemence.”

It’s a sentiment that’s hard to understand when listening to Raining. Bolotin does indulge in a bit of Dylan pastiche on “The Story of Lester and the Gold Coin” and early on was steeped in Cohen worship, but at the core of this collection is a clear, original voice that plucks small scenes from the lives of the brokenhearted and downtrodden to explore them from various angles and in different kinds of light.

A simple bus ride becomes a metaphor for the journey of life (“Driver driver…I put my only life in your hands…You’re the god of all of us/And I honestly hope you are kind”). A broken man walks down a winter street, begging a snowman to stay in one piece because “I’ve already gone through too many changes.” And Linda, the woman from “Go Down Easy” finds her strength and finds another lover even though that man “knows that there’s another/she thinks about when nighttime lays on down.”

There’s a lot of Bolotin in these songs, as well. It’s not difficult to see that the stranger in “The Picture and the Frame,” a man who “stood out sharply in the crowd/these times…perhaps not made for him,” is likely a stand in for the songwriter. But Bolotin did find a way to turn that into a strength. He kept making visual art, eventually befriending a gallery owner from Cincinnati that presented Bolotin’s work. “That’s where I followed my work,” he says, simply.

Bolotin never entirely gave up on music. He just writes with a different mindset these days. There are the scores that he makes for his art films. And a few years back, a stage director from the U.K. produced a version of Bolotin’s work Limbus: A Mechanical Opera that featured the artist’s sculptures. But his songwriting days have somehow continued to track his movements, just as they did that fateful summer day at an amusement park 30 years ago.

“When Mark Linn [founder of Delmore] called me and asked me if I wanted to release these tracks,” Bolotin says, “I said, ‘Do you want to do it because of the songs or because of the stories involved and the somewhat famous people. He gave the right answer. He said, ‘Both.’ I mean, it’s a story and I like stories.”