“Woke last night to the sound of thunder

How far off I sat and wondered

Started humming a song from 1962,

Ain’t it funny how when you just ain’t got as much lose

Ain’t it funny how the night moves…

With autumn closin’ in.”

A hollow acoustic guitar, a slightly dusty male voice aged by the road and experience, a loping groove and a lyric that—like a Japanese ink drawing—takes a few lines and paints a novel. Bob Seger captured the strain of want and release in the heartland from a vantage point many years later. Yet somehow the urgency and viscous element of the moment remain even in the rearview mirror. Songs and the past: there’s nothing quite so intoxicating.

Nostalgia by nature is a sticky, treacly thing. It’s co-opted into an idealization of what was—without the tempering of the hurt, the ache, the suck that often embedded the moments in our psyche.

Many of us, needing solace or balm, reach for the records of our youth. The music that “got us through,” “helped us cope” or truly celebrated how freaking awesome we were before life’s tentacles of responsibility ensnared us.

Beyond returning to those records that mattered, or the concert tours designed to dredge our inner 15-year-olds shrieking at maximum lung capacity, nostalgia offers a far more narcotic reality: the fodder for songs.

Sometimes, those songs—often delivered in merciful soft focus, Vaseline slathered on the lens for diffusion—even tell the harsh truth about looking back. If Bruce Springsteen’s “Glory Days,” with its farfisa organ trills and churning bass part, seems like a bit of carnival cotton candy, listen to the lyrics of the folks trapped in their past, high-school heroes whose lives won’t ever get any better.

Green Day’s uncharacteristically acoustic guitar-driven “Good Riddance (The Time of Your Life)” offers an unflinching shuddering off of what is now behind. Many a high-school prom was soundtracked by the song with the notion of celebration—missing the eschewing of what was.

Still, there’s something wonderful about innocence, about not knowing and dreaming, believing in impossible things. Before the chagrin of wisdom sets in, there is the fuel of youth and beauty, the notion that life is fair, things will last and the way of life our grandparents believed in was worth cherishing.

Whether it’s the Judds’ “Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout The Good Ole Days),” where Wynonna’s dusky voice over a full Martin guitar croons “Did lovers really fall in love to stay…Did daddies really never go away” or John Prine’s gravelly homage “Grandpa Was A Carpenter”—which recalls a man who “chain-smoked Camel cigarettes and hammered nails in things” but also wore a suit to dinner and sang the child “Blood on the Saddle”—a notion of safety and simple things being plenty permeates. Even the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band found the tenderness of looking back in Rodney Crowell’s “Long Hard Road (Sharecropper’s Dream)” potent enough for their first No. 1, albeit on the country charts.

Nostalgia, though, comes in many emotional colors. For Bob Marley, the nostalgia that wafts through “No Woman, No Cry” is used as a solace for the displaced and oppressed; “remember when…” suggests comfort in the despair. The reggae classic unfurls from the government camp in Trenchtown, “And then Georgie would make the fire light as it was logwood burnin’ through the night/ Then we would cook cornmeal porridge, of which I’ll share with you…”

Dolly Parton’s foraged couture in “Coat of Many Colors,” sewn by her mother and mocked at school, provided the bombshell blonde a chance to see the love instead of the scraps that were sewn together.

Small comforts in hard places tiding one over during even more trying times is a trope worth celebrating. Nostalgia is a powerful thing. It is Guy Clark marveling at the wages of time, seeing the grandfather figure he’d revered truly become old in “Desperados Waiting for a Train” measured against the rush and gusto of the big train sweeping through a small Texas town through the eyes of that same child in “Texas 1947.”

In U2’s hands, Martin Luther King’s life is rendered in full heroic glory. The nostalgia igniting “Pride (In The Name of Love),” with Larry Mullen’s drums almost tribal and the Edge’s guitar burning white hot, is meant to lift the listener up, seeking a higher truth or good.

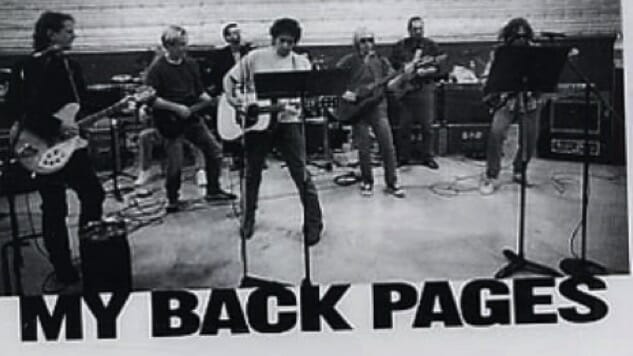

Bob Dylan—and later the Byrds—tapped into that same political passion with more venom and indictment on “My Back Pages.” While so many gravitate to the refrain’s “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now,” the song impales societal bias, our lack of questioning and tackling institutions from the military to religion to school. Ah, nostalgia as a means of awakening.

That same power can give nostalgia a sense of elegy. When you hear Johnny Thunders’ sorrow-soaked “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around A Memory”—tugging enough to later be captured by Ronnie Spector’s little-girl-growing-too-knowing voice and Guns N Roses’ Axl Rose’s trenchant blister—what’s lost endures in the mind.

Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers took that same approach to regionalism. “Southern Accents” slowly unfurls across Benmont Tench’s dropped piano notes and chords and a shaker, Petty’s nasal tenor moaning. An homage to a way of life some consider peckerwood, the Gainesville rocker makes holy through the eyes of a cast-off laborer adrift in a world that has no use for him.

Loser nostalgia, pictures of fading antiheroes, gives many songs their lift. Jimmy Buffett’s pre-“Margaritaville” juggernaut boasts an homage to dope smugglers passing their prime in “A Pirate Looks at 40.” Boat captains living the outlaw life in Key West when the songwriter was languishing pre-stardom were both romantic and heroic in their raging against the system—maintaining their dignity all the while.

That phenomenon—fading with grace—isn’t limited to countrified balladry. For Ron Wood, during his time with the Faces, it was the lilting “Ooh La La,” inverting Dylan’s “Back Pages” with the churning “Wish I knew then what I know now when I was younger” as he recounted his grandfather’s warnings about “women’s ways.”

The Georgia Satellites take an even more brazen approach, with the ribald neo-zydeco rock ‘n’ roll homage to the pleasures and tortures of the flesh on “Shake That Thing.” Dan Baird’s chainsaw twang rips the cover off his vocal chords, as a brazen slide guitar leers at the comely Chiquita down at Miss Kitty Kat’s. Raw lust, a thumping backbeat, pure unapologetic swagger: everything a surging post-sexual awakening contains.

Sexual awakening is perhaps the most potent nostalgia of all. Rod Stewart found the top of the charts with his older-woman homage “Maggie May,” the mandolin and yearning igniting so many people’s memories of their own carnal initiation with impossible partners who knew more—and ultimately would be too old to maintain the flame.

For Deana Carter, her insistence on a five-minute waltz in country radio’s positive uptempo world seemed like career suicide—until “Strawberry Wine,” a bittersweet reminiscence of co-writer Matraca Berg’s deflowering and first summer love with a college boy working on her grandparents’ farm, struck a chord with its tenderly bruised reflection: “caught somewhere between a woman and a child/one restless summer, we found love growing wild/on the banks of the river, on a well beaten path/It’s funny how those memories last like strawberry wine…”

In the rearview, it’s all so easy. None of the doubt or discomfort; only the good parts. Midwestern favorites the Michael Stanley Band plowed the same ground in “Somewhere in the Night,” another song about being “17 and caught in between what I was and what I wanted to be.” That loss-of-innocence anthem, though, contains a truth that binds everyone of these songs—from yearning to angry, idealistic to lustful—together: “All you get to keep are the memories, and you gotta make the good ones last.”