David Berman is back—despite his best efforts, it seems.

For 15 years bookending the turn of the 21st century, Berman was not only the primary creative force behind indie-folk faves Silver Jews, he was considered by many to be the poet laureate of the underground. Across six solid albums—peaking with 1998’s American Water—his songs spilled over with double-take-worthy wisdom and witticisms built from approachable language. Put another way: Berman’s lyrics were always incredibly clever, but they never felt strained.

Around 2009, though, he disappeared from public life, apparently discouraged by a less-than-glowing review of his final Silver Jews album, Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea. So, as he said in a recent interview, he decided to shutter the project.

“I felt like I probably wasn’t going to do better than that album,” he said. “Maybe another person could if I went away for a while and came back a different person.”

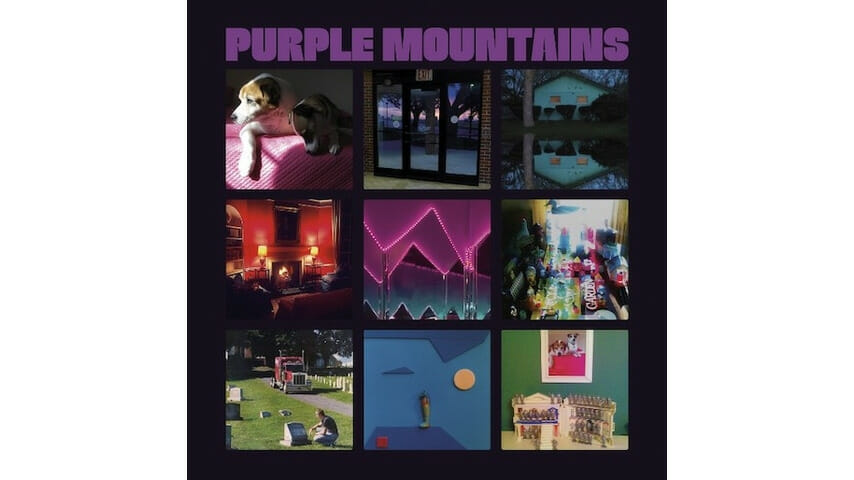

On his new album—self-titled and released under the name Purple Mountains—Berman doesn’t sound like a different person than the one that walked away a decade ago. He sounds like himself, an endlessly thoughtful and unnervingly honest master arranger of words. He is still an adequate singer, limited by his flat and shaky voice, but he sounds rejuvenated, perhaps buoyed by his new backing band, the Brooklyn psych-folk group Woods.

The most striking sonic element of Purple Mountains is how many upbeat songs there are, given the brooding themes throughout. “All My Happiness is Gone” is a punchy rocker with a prominent Mellotron hook that cuts right through the devastating sentiment in its title. “Margaritas at the Mall” pairs existential worry with warm trumpet lines and swooping pedal steel guitar. The album’s closer, “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,” is a loner’s anthem dressed up in classic country twang. Only on the record’s catchiest tune, “Storyline Fever,” does Berman sound like he’s having to work to keep up.

Elsewhere, he ditches the semantic flair for “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son,” a sweet, plainspoken tribute to his mother who has passed away. “She was so good and kind to me. She was, she was, she was,” Berman sings against the song’s gentle sway. He follows it with “Nights That Won’t Happen,” a dreamy meditation on death in which he describes the separation of the dead and the living as “nights that won’t happen” and “time we won’t spend with each other again.” It’s a nifty trick—a way of looking at death that humanizes and crystallizes an otherwise unknowable concept.

Rest assured, Purple Mountains teems with great Berman-esque wordsmithery. The second line of the first song, “That’s Just the Way I Feel,” succinctly summarizes his creative exile as “a decade playing chicken with oblivion.” “Darkness and Cold” is built around the line “the light of my life is going out tonight without a flicker of regret,” a brilliant bit of twisting, turning wordplay. Show-don’t-tell descriptions litter the landscape: A “Band-Aid pink Chevette” here, the “icy bike-chain rain of Portland” there. In “That’s Just the Way I Feel,” he unearths this gem: “When I try to drown my thoughts in gin, I find my worst ideas know how to swim.”

That’s one more thing that hasn’t changed about David Berman: He’s just as bummed out as ever on Purple Mountains, and he still makes being bummed out sound better than just about anyone else.