This story originally appeared in Issue #4 of Paste Magazine in the fall of 2003, republished in celebration of Paste’s 20th Anniversary.

This story originally appeared in Issue #4 of Paste Magazine in the fall of 2003, republished in celebration of Paste’s 20th Anniversary.

![]()

Lord, hear our penitential Cry:

Salvation from above;

It is the Lord that doth supply,

With his Redeeming Love.

Ho! every one that hunger hath,

Or pineth after me,

Salvation be thy leading Staff,

To set the Sinner free.

—Jupiter Hammon, from “An Evening Thought”

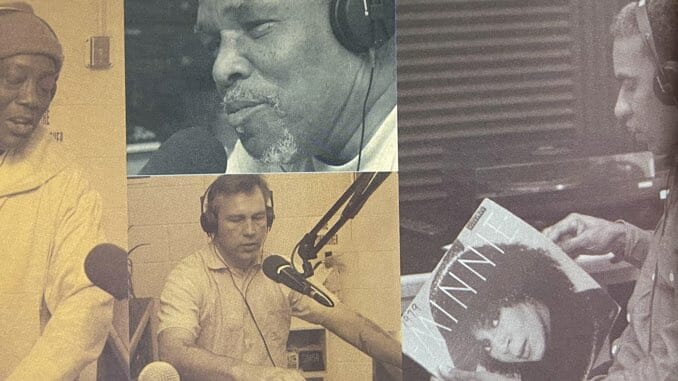

At first glance, it could be the broadcasting booth of a college radio station. A poster advertising a recent film symposium hangs on the wall; people are mopping up after the rain, working on newly acquired equipment, queuing up CDs. The DJ looks through the newspaper and marks the stories he will read on air, most of which regard Louisiana corrections. There are no armed guards, no nametags—nothing to indicate that this is a maximum security prison. Looking around, I can see why inmates would want to work here. For a moment, we could be anywhere else.

“The radio station helps me to relieve stress and tension,” the Reverend A.J. explains. The 71-year-old inmate serving a life term for first-degree murder looks gentle and grandfatherly. If this were indeed a college campus, A.J. would be a model student. Here at Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola), he is a member of the Lifer’s Association, Chairman of the Elderly Assistance Group and hosts a gospel show on KLSP, Angola’s radio station. He visits sick prisoners in the hospital and preaches to other inmates during church functions.

“I’ve done so much wrong to people,” he says. “Now that I have the chance to give back, that’s what I do.”

Reverend A.J., whose full name is Andrew Joseph, first came to Angola in 1948. “When I came to prison, [it] wasn’t a place of rehabilitation. Everything was survival.” As a 17-year-old kid who “attracted the older inmates,” A.J. survived by “develop[ing] a violent attitude.” He was in and out of correctional facilities several times before being sentenced to life in 1978. About 10 years ago, Burl Cain, Angola’s warden asked him to become involved with the radio station.

“Just to realize that I was counted as a trustworthy inmate to work at a radio station was a big deal for me,” A.J. says. “I jumped at that.”

KLSP is the only FCC-licensed radio station in the country facilitated by inmates, and it’s an integral part of Angola’s unorthodox approach to inmate rehabilitation. The station was established under a previous warden in 1986 as a means of communicating with everyone in the prison at once. Angola is the country’s largest correctional facility, with 5,108 inmates, so the need to disseminate information rapidly is critical.

KLSP is licensed as a religious/educational station, and, through Cain’s efforts, has formed a close alliance with Christian radio. Until recently, the station was using hand-me-down equipment courtesy of Jimmy Swaggart; last year, His Radio—Swaggart’s Greenville, S.C.-based network of stations—held an on-air fundraiser for the prison, broadcast live from Angola. They quickly surpassed their $80,000 goal, raising over $120,000 within hours. Cain used the money to update the station’s flagging equipment and train inmate DJs in using the new electronic system. In the months following their initial partnership, Cain deepened his relationship with Christian radio stations. KLSP now carries programs from His Radio and the Moody Ministry Broadcasting Network (MBN) for part of the day.

Despite new alliances, the majority of the station’s broadcasting decisions remain in the hands of inmates like 43-year-old Robin Brett Polk, who has been in the prison “somewhere around 21 years.” He has a radio show on KLSP that plays Christian rap and R&B.

“Music has helped me to keep myself focused on trying to straighten my life out,” Polk says. “It taught me to be a dependable person.” With few opportunities to see his family, most of Polk’s socialization comes from inside Angola. When he is not at KLSP, where he has worked for several years, he can often be found practicing with the prison gospel band, in which he plays bass.

“Prison is sort of like a family,” he says. “The inner family for me is the musicians I play with.” The entire correctional family tree is enormous—Louisiana has the largest per capita incarceration rate in the country, and the average sentence at Angola is 88 years.

“I bury more than I release,” says Warden Cain. Victim’s rights groups are powerful in Louisiana, a state notoriously tough on crime. “The challenge is for the people to forgive one another more,” says Cain. “We all make mistakes.”

But with little relief for the state’s crowded facilities in sight, Cain finds himself presiding over an aging prison population and, as inmates pass away, dealing with the bodies of unclaimed prisoners. They used to be buried in cardboard boxes, until one incident where a man fell through the bottom. Cain instituted a policy change—now inmates manufacture coffins themselves in a factory on the grounds.

Angola is located at the base of the Tunica hills in a breathtakingly beautiful region of Louisiana. Though individual camps containing sleeping and recreational quarters are fenced in, the facility is walled only by the hills and the Mississippi River. The sight of inmate trustees in jeans and T-shirts hanging out at KLSP or working the front gate makes it feel like a pastoral society. Watching rows of inmates work the fields of Angola’s farm, however, is less comforting. The prison sits on the land of a former plantation and slave breeding ground (named Angola for the African country from which its slaves were sent). After the Civil War, plantation owner Samuel L. James leased Louisiana’s inmates, housing them in slave quarters. At the time, this was a relatively uncontroversial move—courts ruled that a prisoner “not only forfeited his liberty, but all his personal rights except those which the law in its humanity accords to him. He is for the time being a slave to the state” (Ruffin v. Commonwealth, 1871). The prison, whose population is 76.7% black, is still a working farm, with each inmate laboring about eight hours a day on the 18,000 acre site. Many prison officials refer to outsiders, such as journalists, as “free people.”

Burl Cain will be the first to say that a prison takes on the character of its warden. He is a charming, charismatic man with a George W. Bush-like appeal—the down-home everyman just trying to make the world a better place. A big man with a thick Southern drawl and disarmingly candid manner of speaking, Cain possesses qualities to which many of the inmates seem to react positively. While I was there, the warden held a meeting with leaders from various inmate clubs at his ranch house. They gathered around his table and ate snacks as the warden answered questions about their concerns. Inmates spoke freely, and Cain was friendly and jovial. Everything was recorded for broadcast on KLSP.

The warden is also a deeply religious man, and as such, Angola sometimes feels like disciplinary Bible camp. A plaque near the prison’s front entrance quotes from Philippians, and the annual prison rodeo includes a lengthy parade wherein Jesus’ story is acted out on horseback. The only on-site facility of higher education at Angola is the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, where inmates can earn a degree in Christian ministry. According to the prison’s inmate-produced newsmagazine, The Angolite, the “Level One” disciplinary cells afford only “a white jumpsuit, religious book, pad of paper and pen, and legal papers” to each prisoner.

The emphasis on Christianity is thought to have a civilizing effect on inmates. Cain insists “the only true rehabilitation is moral rehabilitation.” He speaks to churches and religious leaders across the country about Angola’s programs, and elicits partnerships with likeminded groups, such as His Radio and MBN, whenever possible.

“We’re feeding them good material,” Cain says. According to His Radio’s website, the warden has invited the Christian programmers to return every six months to “maintain the equipment and help train the inmate DJs to minister more effectively.”

Rehabilitated inmates are able to lead a somewhat normal life, and Cain is very matter-of-fact regarding his methods. “You’re supposed to obey the law of the land,” says Cain. “It says it in the Bible. If you respect authority, then you will respect authority.”

Traditionally, those who do not respect authority have suffered strict consequences—in the infamous “Angola 3” case, inmates were placed in solitary confinement for nearly 30 years. Just last year, an inmate was prevented from testifying at his own trial after several courtroom outbursts. Baton Rouge’s daily newspaper, The Advocate, described Angola’s method of dealing with the rebellious inmate: “Louisiana State Penitentiary security officers wrapped the bottom half of his face and all of his neck with duct tape, then wrapped a circle of tape under his jaw and over the top of his forehead.”

More recently, Warden Cain has acquired wolves that he hopes will replace the guard dogs. He expresses an almost childlike optimism about their psychological effect. “You’re more afraid of a wolf than you are of dogs,” he explains, “so if I have a wolf that’ll bite, then the wolf will never have to bite anybody, because nobody will want to be challenged by the wolf.”

The prison’s emphasis on faith-based rehabilitation programs and strict punishments raises eyebrows with civil rights groups like the ACLU. Joe Cook, the executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana, calls many of the warden’s methods “highly suspect.”

“From what we’ve seen and what we’ve heard,” Cook explains, “it appears the administration favors religion over nonreligion and that does offend the First Amendment.” The ACLU has fielded complaints that Angola’s administration has withheld certain privileges from those inmates who have not found God.

The inmates I met at KLSP were all articulate and smart. Two of the DJs, Reverend A.J. and Leotha Brown, are graduates of the on-site seminary. It seems that their lives have been made better by the opportunity to be involved with the station. If, at the end of the day, Warden Cain’s promotion of religion helps inmates like those at KLSP, is he really doing any harm?

Joe Cook claims there is “no scientific evidence” to back claims that faith-based programs work better than others. More importantly, he points out, “even if there was some connection, it doesn’t make it legal.”

The Supreme Court ruled in 1947 that “[n]either a state nor the Federal Government… can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another…” and that “[t]he First Amendment has erected a wall of separation between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable.” (Everson v. Board of Education, 1947).

“I’d like to see Warden Cain honor the Constitution and the rule of law,” says Cook. “If those in charge of enforcing the law break the law, that sends a terrible message.” Cook is fighting an uphill battle, as Louisiana traditionally has had a pro-Christian legislature. “The prevailing sentiment is that this promotion of religion is a good thing,” Cook explains.

Cain believes that his method of rehabilitation works, and he has the support of state officials. “They can get out and become productive citizens,” he explains, or “as long as they don’t go out, they have a real calming effect for us over this prison. And you bring God into it and say, ‘God intends for you to be here, and you’ve redeemed yourself. You can’t get out of here, but you’ll be blessed later.”

The Reverend A.J., who has never applied for a pardon, agrees. “People don’t want to hear that I’m a Christian now—everyone goes [before] the board with the same story. People don’t think you can change. Maybe I deserve to be here; I don’t know.”