Should there be any limits on the depictions of sex in music?

The instinctive response is, “No, not at all. Let it all hang out. Let a thousand orgasms bloom.”

Let’s make the question a little more challenging: Should a song that graphically describes anal sex between two consenting adults (whatever their genders) be played on broadcast TV? On cable TV? On broadcast radio? On satellite radio? On YouTube? On Spotify? If so, should it be labeled somehow? Even if you’re okay with all that, is such a focus on sexual plumbing compatible with artistic success? If it is, what would that sound like?

Let’s make the question more challenging yet: If the song describes the violent rape of a terrified 12-year-old girl from the perspective of the unrepentant rapist, should any limits be imposed? If so, what should those limits be? Government censorship? Government labeling? Exclusion from major-label record companies and broadcast radio? Labeling by record companies? Banning from certain campuses and workplaces? Condemnation and/or boycotts by listeners, both professional critics and amateur fans? Self-restraint by the artist? And if there are no limits, is it possible to create genuine art out of such subject matter?

The debate over sex in music was clearly defined through the 1970s. Arguments weren’t about accounts of actual sex; they were about how thinly veiled the euphemisms for sex could be. It became increasingly obvious, however, that both the government and the music industry were being hypocritical in refusing the creators of pop music the same freedom of expression that the authors of books had long enjoyed.

But as we advocates of civil liberties won victory after victory over the crumbling forces of censorship, the floodgates opened—and not everything that washed in was welcome. Along with the songs we wanted—the perceptive evocations of sex between consenting adults—we also got the shallowest forms of titillation and the ugliest kinds of sexism. Be careful of what you wish for; you just might get it.

Let’s take two issues off the table. Let’s agree that no democratic government should ever ban a work of art or journalism. (Disputes over copyright ownership are another matter for another time). And let’s agree that no adult should be prevented from listening to songs about sex between consenting adults.

That still leaves some thorny issues. For example, should children be shielded from certain subject matter? If so, to what age? 12? 16? 18? Who should do the shielding? Broadcast TV and radio? The internet? Schools? Parents? If it’s left to the parents, do they deserve the same kind of consumer-protection labeling that progressives have demanded for food products? Do they deserve enough facts to make an informed decision?

Tipper Gore and her Parents Music Resource Center pressured the record companies into adopting just such a labeling system in 1985. During Senate hearings on the proposal, Frank Zappa attacked the labels as “an ill-conceived piece of nonsense which fails to deliver any real benefits to children, infringes the civil liberties of people who are not children, and promises to keep the courts busy for years dealing with the interpretation and enforcement problems inherent in the proposal’s design.” Everyone from Ice-T to John Denver piled on.

When retail chains such as Wal-Mart, Sears and J.C. Penney refused to sell records with warning stickers, the supposedly informational labels became de facto censorship. This brings up another sticky issue: Do stores have First Amendment rights? Is Wal-Mart entitled to express its own view of popular culture by choosing what to sell and what not to sell? Or is it obligated to sell whatever’s popular? Does your local, hole-in-the-wall punk-rock store have the same obligation? Or do large corporations have different responsibilities than stand-alone shops?

How about large media companies? Do the CEOs of Universal Music, YouTube and VH1 have First Amendment rights? Can they choose what songs to distribute and what songs to ignore? Or are they obligated to provide a non-judgmental channel for all comers? Do concert promoters, disc jockeys and internet curators have the First Amendment right to choose what music to present and what music not to present? Or does the First Amendment only apply to songwriters and performers?

These are not easy questions to answer, because in a capitalist society large corporations wield so much power that their censorship can feel a lot like government censorship. If Sony and Universal were to suddenly decide that they wouldn’t release any more songs about blow jobs, then much of the North American audience—especially those people living outside large cities—would be deprived of an artistic consideration of blow jobs.

Why would that matter? Is there such a thing as art about oral sex? There should be. Getting and/or giving head is a crucial experience for most humans: often thrilling, almost as often troubling. At times it’s a strange substitute for genital sex or full romantic commitment; at other times it’s a special favor that demonstrates an elevated level of passion. Can these mixed feelings be addressed in song?

From cunnilingus tunes such as Khia’s “My Neck, My Back (Lick It)” and Missy Elliott’s “Work It” to such fellatio numbers such as Aerosmith’s “Love in an Elevator” and NERD’s “Brain,” most songs about oral sex are single-minded celebrations of its pleasures and/or invitations to a lover to service the singer. Such songs can be fun, but where are the songs that explore our more complicated feelings?

Leonard Cohen uses mumble-mouthed melancholy to discuss a blow job in “Chelsea Hotel #2,” reportedly based on his brief fling with Janis Joplin in the Manhattan hotel. Whoever the woman was, she is described as “clenching” her fist and “giving me head on the unmade bed.” But the song is less interested in the 10 minutes of fellatio than in the many years that the memory lingers. The singer protests that he doesn’t think of her often—he “can’t keep track of each fallen robin”—but he obviously remembers it enough to write this song about the one who “got away.” We think brief sexual encounters can be easily forgotten, but Cohen realizes it’s not that easy.

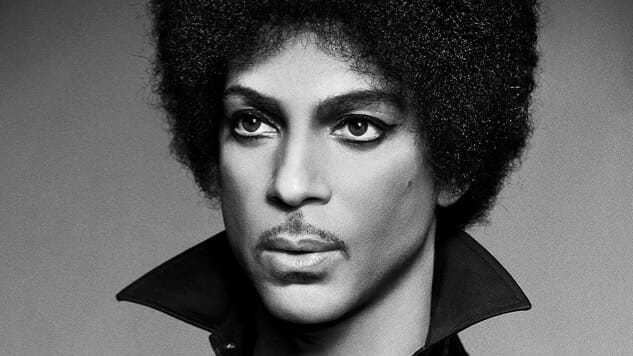

Prince tackles oral sex with funk-fueled humor on “Head.” A girl who’s trying to preserve her virginity for her upcoming wedding to someone else offers to give the singer a blow job. She seems to believe, as do so many others, that oral sex isn’t real sex, that her virginity is intact even after she’s swallowed his semen. But she’s so stimulated by the experience that she rips off her clothes and goes all the way. It’s a funny song, but it acknowledges that feelings are tied to sex. She agrees to dump her fiancee and marry the singer, who shows his gratitude by going down on her. It’s one of the rare songs to emphasize reciprocity rather than narcissism in sex.

Reciprocity is key. It’s enjoyable to hear consensual sex praised in rhythms that echo the physical action and in melodies that reflect the emotional giddiness. What’s not enjoyable is hearing an insecure male overcompensating by boasting about coercive sex. When A$AP Rocky—a gifted vocalist but a creepy right-winger when it comes to sex, guns and money—brags on “Goldie” that he’s going to “tell that bitch” to “suck the dick,” he doesn’t illuminate sexuality, he obscures it. By erasing the personhood of his sexual partner, he obliterates the world outside his ego and thus destroys the chance of successful art.

How are we to respond to a song like this? With less First Amendment freedom? No, we should respond by exercising our own rights—as critics, consumers and/or citizens—to condemn such Trumpian sexual attitudes. And we should balance that by acclaiming the songs about sex that fully acknowledge both partners as well as the complex feelings that accompany the action.