Taylor Swift, Fiona Apple and The Mystery of Music Made in Isolation

There are some eerie parallels between the singers’ new albums, but is that just the quarantine talking?

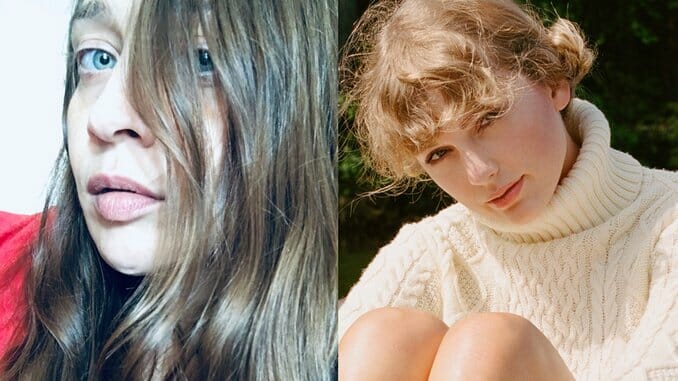

Photos by Fiona Apple & Beth Garrabrant Music Features Taylor Swift

Try as you might to find the similarities, Fiona Apple’s Fetch The Bolt Cutters and Taylor Swift’s folklore are almost nothing alike. During normal, sane times, I wouldn’t dare try to compare two artists who make such wildly different styles of music.

But these aren’t normal times. Now, nearly five months into the time vacuum that is quarantine, the music and media released during these strange COVID times are starting to become more and more homogenized in our minds—no matter when they were created. We’re sick of reading why Palm Springs is the perfect quarantine movie or how Apple’s album was incredibly clairvoyant, but this type of coverage is not going to stop. We can’t help but connect the art we’re hearing right now to the difficult and often disheartening times we’re in.

As it turns out, that act of connection is also happening between albums themselves. Fetch The Bolt Cutters feels relevant to the Taylor Swift discourse, and vice versa. The main parallels between the two albums involve the recording processes. When Apple released FTBC in April, think-pieces exploded across the internet about how eerie it was that she managed to capture exactly how our current kind of mass isolation (is that an oxymoron? I’m tired) feels. But Apple isn’t a psychic; she’s just a a very private person, and, while FTBC is a pre-COVID project, she recorded this album over the course of several years inside her California home, allowing only select artifacts and people from the outside world inside. The resulting music is something so much grander than songs about loneliness or romantic dissonance, but, as Emily VanDerWerff wrote in a piece for Vox, “what most resonates throughout Bolt Cutters is the feeling of being trapped somewhere, slowly unraveling, impotently furious about a world that is tearing itself apart without your consent.” Sound familiar?

Swift wrote her latest masterpiece (yes, I said it!) in isolation. But, in her case, the music was, for the most part, written and recorded entirely during the last few months—making folklore a true quarantine album. folklore sprung directly from having abundant free time due to Swift’s summer tour cancellations and an overactive creative mind. As she puts it, “In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve.” She and a talented team of partners including Jack Antonoff, Aaron and Bryce Dessner and others contributed to this album from different rooms and, in some cases, different states, in what was probably an effort to maintain social distancing. The song “exile” (which features Bon Iver) refers to a metaphorical kind of distance, but it’s somber enough to feel relatable to our current moment of separation. The whole release was a secret, which means we still don’t know a lot about what went down between Swift, Dessner and the rest of the team (Dessner disclosed he was bound to strict secrecy, even keeping the project hidden from his family). As is the case with Fiona Apple’s unique artistic process, we will be speculating about the creation of folklore forever.

There’s not much “wonder” and “whimsy” on Apple’s latest output, but there still seems to be something (maybe an “invisible string”?) linking the souls of these two albums together. Notably, both touch on (or, in Apple’s case, maybe “kick at” is a better phrase) society’s tendency to cast women as crazy, hysterical, hormonal nutcases who can’t control their feelings or actions. On FTBC, Apple is overly animated at a dull dinner party, but good luck getting her to “calm down,” as so many men have commanded women to before: “Kick me under the table all you want,” she sings. “I won’t shut up.” She later adds one of the best lyrics of the year (“I would beg to disagree but begging disagrees with me”) which, in a way, is similar to the sharp wordplay on Swift’s “the 1,” where she sings, “In my defense I have none.” For Apple, that frustration is realized in the album’s rallying cry: “Fetch the bolt cutters / I’ve been in here too long.”

Swift zeros in on one “crazy” woman in particular on folklore: Rebekah West Harkness, an infamously zany divorceé from St. Louis who married William Hale Harkness, the heir to the Standard Oil company, before he died in 1954, and purchased a vacation home (nicknamed “Holiday House”) on the coast of Rhode Island, where she reportedly shocked the locals frequently with her shenanigans. The twist? Swift now owns that mansion, and she uses Rebekah’s story to craft a vivid tale on “the last great american dynasty.” In the song, Swift describes Rebekah’s antics while the neighbors gossip, “There goes the most shameless woman this town has ever seen / She had a marvelous time ruining everything.” But then she switches the narrative to first person, as she is often wont to do, singing, “There goes the loudest woman this town has ever seen / I had a marvelous time ruining everything.” Voila.

They have vastly different musical styles (Swift toggles between glitchy indie-pop and dreamy acoustic bliss on folklore, while Apple prefers sharp, experimental beats and unhinged melodies), and Swift tends to beat around the bush where Apple is more direct, but folklore and Fetch The Bolt Cutters share a wild, female energy and a precision that could only be made by artists at the top of their game. We don’t know exactly what the recording and writing processes looked like for these two albums, but I imagine both began the same way: with a woman, and a piano.

So, maybe Apple and Swift actually do have more in common than meets the eye: Free of the pressures, schedules and demands that dictate a standard album cycle, they both made some of their best work in isolation. Just because one artist is considered a “serious” indie musician and the other a purveyor of sugarspun pop songs doesn’t mean they’re not both geniuses. You don’t need permission to hold Swift to the highest standard as an actual artist and not just a hit machine. You also don’t need permission to interpret the music you hear in 2020 through the lens of a person alive in 2020—because you are. If anyone tries to tell you otherwise, well, fetch the bolt cutters.

Ellen Johnson is an associate music editor, writer, playlist maker, coffee drinker and pop culture enthusiast at Paste. She occasionally moonlights as a film fan on Letterboxd. You can find her tweeting about all the things on Twitter @ellen_a_johnson.