The Curmudgeon: Reimagining The Monkees

What If the Auditions Had Gone in a Different Direction?

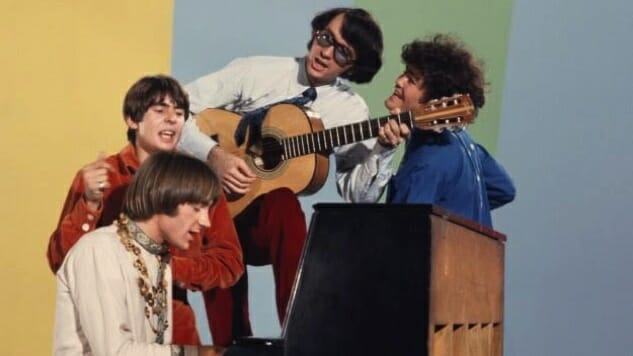

Photo courtesy of Rhino Records Music Features The Monkees

When Peter Tork died last month, it was a reminder that he, Michael Nesmith and Mickey Dolenz weren’t the only young men who auditioned for the final three slots in the Monkees line-up. In 1965, the producers of the NBC TV show, having already hired child star Davy Jones as a lead singer, looked at more than 400 applicants for the roles, including such soon-to-be-famous figures as Stephen Stills, David Crosby, Danny Hutton, Paul Williams, Harry Nilsson and Van Dyke Parks. What if the producers had gone in a different direction with the casting?

Imagine TV producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider sitting at a long, cherrywood table in a windowless Los Angeles conference room with Brill Building music publisher Don Kirshner. Imagine them discussing the Stills’ audition.

“He’s the only one of these clowns who can really sing and play guitar,” Rafelson says.

“He’s ugly,” rejoins Kirshner. “He’s got bad teeth,” agrees Schneider. “We want guys who are cute enough that girls will tape the photos to their bedroom mirrors. Look at the Beatles; they would never have made it if they weren’t so cute.”

“You’re out of your fucking mind,” Rafelson shouts. “The Beatles were the real deal; that’s why they were so successful. If we want this show to last more than two seasons, we need to have musicians who can play and write songs. This kid Stills and his friend Crosby; they can do that.”

Back and forth they go for more than an hour. Schneider and Kirshner are arguing for Michael Nesmith, Mickey Dolenz and Stills’ other friend Peter Tork to join Jones in the line-up. Rafelson won’t give up. He wants Crosby, Stills and Nilsson. They are getting nowhere when there’s a knock at the door. In walks a scruffy-looking, 29-year-old guy with wild hair and squinty eyes.

“This is my friend Jack Nicholson,” Rafelson says. “You may have seen him in the Little Shop of Horrors flick that Roger Corman did. He’s hip to what young people like, and I thought he could give us some useful perspective.” Nicholson pulls up a chair and doesn’t say anything for a while. Ten minutes later, he starts talking and won’t stop.

“Look, you guys are trying to create a TV show that copies the Beatles’ Hard Day’s Night, he says. “Not a bad idea. But what you need to do is create a rivalry between the band of good guys and another band of bad guys, like the Beatles vs. the Stones. Jones and those cute guys can be the good band, and Stills and those guys can be the bad band. That Hutton kid can be their lead singer. That way you get the young girls who like the cute guys and you get the gnarly boys like me who like the rebels. You’ll double your audience.”

The producers are stunned that this barely employable actor can talk the language of increasing market share. But they’re intrigued. What would we call the other band? Dozens of names are tossed out, all of them lame.

“Call them the Gorillas,” Nicholson says decisively, “only spell it G-O-R-I-L-L-A-Z. And spell the Monkeys M-O-N-K-E-E-S.” (Years later, a British singer would have to name himself after a Bowie knife, because the name Davy Jones was already taken. Another British singer, Damon Albarn, would have to name his animated group the Chimpz, because Gorillaz was already taken.)

There is no sign of the Gorillaz in the first two episodes, which introduces the Monkees as madcap young lads living in a California beach house and playing catchy pop-rock songs between whacky antics. It works. The ratings go through the roof, and the newspapers give them lots of ink.

The Gorillaz are finally introduced in the third episode. The Monkees enter a local “Battle of the Bands,” only to find that their competitors in the final round are the Gorillaz, scowling, smoking cigarettes and wearing black leather like classic movie villains. Near the table with the punch bowl and the plates of cookies at a teenage rec center, the Monkees try to play nice, shaking hands and tossing their bangs in a friendly fashion. But the Gorillaz respond with rude sarcasm.

The Gorillaz go on first and play “Sit Down, I Think I Love You,” with Stills on lead vocal and slide guitar, Crosby on bass and harmony, Nilsson pumping chords on a Farfisa organ and Hutton stomping on the kick drum. The rough-edged garage-rock arrangement seems to baffle the clean-cut kids on the dancefloor. The Monkees follow with “The Last Train to Clarksville” in an energetic pop arrangement with lead vocals by Dolenz. The teenagers on the set cheer their approval. The four Monkees bounce up and down goofily as they accept the trophy, while the Gorillaz slink away sullenly.

The next morning, however, in high-school hallways and cafeterias all over America, debates erupt over who should have won the talent show. The cheerleaders, jocks and student government types argue the Monkees were clearly better, while the greasers, beatniks and “bad girls” insist that the Gorillaz were cheated out of a deserved victory. The arguments rages for weeks, pushing up the TV show’s ratings, just as Nicholson had predicted.

When “The Last Train to Clarksville” and “Sit Down, I Think I Love You” are released as singles, the two sides of the debate can vote with quarters from their allowances. The Monkees’ first single reaches #1, and the Gorillaz’ debut goes to #7. The Battle of the Bands plot was clearly a winner, so the show’s writers keep hatching new variations on the theme.

Two episodes later, Stills is a high-school student, whose girlfriend is suddenly flirting with Jones. When they confront each other in the hallway between classes, Stills warns the British transfer student to keep his hands off Cindy Lou. Jones teases his angry antagonist, saying, “I thought you Americans believed in freedom of choice.” Stills delivers a corny joke about the Boston Tea Party, but there’s genuine feeling in his sneer and clenched fist before a teacher says, “You can settle this at tonight’s talent show.”

The curtains part to reveal the Monkees in their mod outfits, singing their theme song: “Here we come, walkin’ down the street. We get the funniest looks from everyone we meet. Hey, hey, we’re the Monkees, and people say we monkey around, but we’re too busy singing to put anybody down.” They exit grinning and waving to the cheering fans. Cindy Lou gazes adoringly at Jones.

The Gorillaz follow with their own stomping, growling version of the same song: “Here we come, marchin’ down the block. People slam their doors and turn the locks. Hey, hey, we’re gorillaz, and we don’t monkey around. We’re gonna start a riot, when we come to your town.” Looks of horror are seen on the faces of the TV extras, but in certain households, certain teenagers are singing along by the end of the song.

A few episodes after that, the Gorillaz and the Monkees both advance to the finals of the California State Music Championship. Stills, with his shaggy, sandy hair, leads his band through his new song, “For What It’s Worth,” about the recent anti-curfew riots on Sunset Strip. With its ominous warning, “Something’s happening here,” and its haunting, chiming guitar figure, it’s a hypnotic downer. After a mix of cheers and boos for the Gorillaz, the curly-haired Dolenz makes a short speech about the importance of young people remaining positive and optimistic. He then leads the Monkees through Neil Diamond’s “I’m a Believer,” and the TV extras go bananas.

The animosity manufactured by the script writers is reflected in real life, though not how you’d expect. Tork often sneaks off with Stills to smoke dope, and they are usually joined by Nesmith, Crosby, Nilsson and Hutton. It’s Jones and Dolenz who resent the Gorillaz stealing the spotlight from a show that is, after all, called The Monkees.

In the world of the show, the Monkees always came out on top, consistently winning the contests and the most desirable girls. On the Billboard charts too, the Monkees are coming out ahead. But in the real world of L.A.’s twentysomething musicians and actors, Jones and Dolenz are acutely aware, the Gorillaz are considered the hipper band. When Lester Bangs writes a 3,000-word essay in Creem Magazine, “How the Gorillaz Are Winning by Losing,” the Monkees’ fate is sealed.

It doesn’t help matters that reporters start pointing out that the Monkees don’t write many of their songs nor play on many of the tracks, while the Gorillaz do. Exacerbating the tensions is Stills, who ad-libs lines to get in digs at Jones and Dolenz. When Jones tells Stills, “You’re nothing but a hoodlum,” for example, Stills is supposed to say, “I may be a hoodlum, but you’re just a Monkee.” Instead Still sneers, “I may be a hoodlum, but you’re just someone’s pet.” Jones insists that they re-tape the episode, but Rafelson uses the take with the ad-lib.

The Monkees’ songs are mostly written by Kirshner’s stable of songwriters: Diamond, Carole King, Tommy Boyce, Bobby Hart, Jack Keller, Neil Sedaka and Gerry Goffin. The Gorillaz’ songs are mostly written by Stills, Nilsson and Crosby. Some of their best material, though, comes from Randy Newman, an obscure L.A. songwriter who is a friend of Hutton and Van Dyke Parks, the failed Monkees auditioner who has become the Gorillaz’ studio arranger/producer.

Newman’s misanthropic sentiments fit the Gorillaz’ characters, but his pop hooks make them popular. “Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear,” sung by Crosby over Parks’ carnival-calliope arrangement, goes to #1. “Mama Told Me Not To Come,” heartily sung by Hutton, provokes a minor controversy with its oblique reference to marijuana. Most controversial is Nilsson’s vocal on “Davy the Fat Boy,” which the Gorillaz insist has nothing to do with Jones, despite his outraged protests.

The whole situation is too unstable to last. Jones and Dolenz find themselves feuding with Tork and Nesmith as much as the Gorillaz. Stills and Crosby have started harmonizing after-hours with another British immigrant, Graham Nash. Hutton and Nilsson are doing the same with Cory Wells and Chuck Negron. Nesmith is experimenting with a new blend of country music and rock’n’roll. As fun as it has been to play cartoon heroes or cartoon villains and sell millions of records, it is time to make adult music. Everyone is ready to move on.

Schneider and Nicholson team up with Dennis Hopper to make Easy Rider. Rafelson and Nicholson make six movies together, including Five Easy Pieces, The King of Marvin Gardens and The Postman Always Rings Twice. Kirshner goes on to host Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert and to launch another TV show about a fictitious band, The Archies.

Before it all falls apart, however, Rafelson directs his first movie, Head, about the Monkees and the Gorillaz. Nicholson plays an unscrupulous concert promoter who promises both the Monkees and the Gorillaz that they will headline a giant music festival in the mountains near Taos, New Mexico. When the bands arrive at the festival site, they discover that Nicholson’s character has made the same promise to the Beach Boys and the Jefferson Airplane. A fistfight breaks out between Nicholson and the Gorillaz and quickly spreads to the Monkees, reaching slapstick proportions worthy of the Three Stooges.

After a blackout, the camera shows the musicians bloody and dazed. Nicholson has split with the box-office proceeds; the audience and other bands are gone. But standing over the battered Monkees and Gorillaz is an American Indian chief as old and wizened as the figure on the buffalo nickel. He beckons the dazed musicians to follow him and soon everyone is sitting cross-legged in a teepee, passing around a peace pipe.

We’re never told what’s in the pipe, but soon the screen explodes into psychedelic effects as the eight musicians go wandering in the mountains amid glowing globules of swirling color. They run into a women’s hiking club (conveniently comprised of eight attractive coeds) from the University of New Mexico, and the women join the shenanigans. Eventually, the eight musicians join forces in a new group called the Primates. Jones sings the Youngbloods’ “Get Together,” but Nilsson has the last laugh, singing Newman’s “I Think It’s Going To Rain Today,” a song that casts doubt on the very brotherhood that it’s preaching.

Watch The Monkees in concert at the Sun Theater in Anaheim, Calif., in 2001 from the Paste Music Vault below.