The identity of The Shins became centered on its soft-spoken frontman James Mercer just before the release of 2012’s Port of Morrow. At that time, the now 46-year-old singer/songwriter had to prove that this project still had staying power beyond the tidal wave of buzz he rode through the mid-2000s while also restaffing the entirety of his backing band.

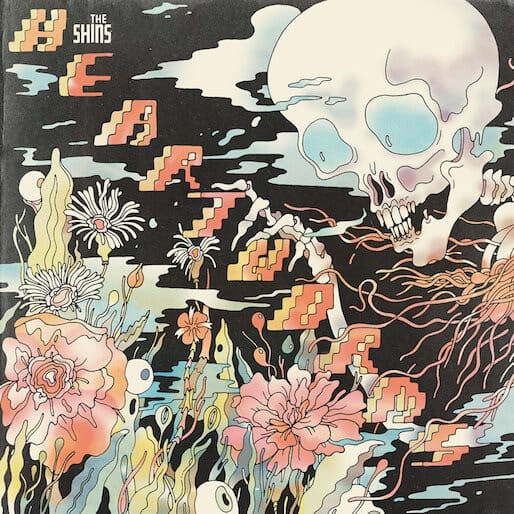

While he succeeded in taking The Shins to its biggest commercial highs (Morrow landed at #3 on the Billboard 200), this shift in focus from a group mindset to one-man-band was accompanied by a period of deep self-contemplation. What came out of that mode is Heartworms, a touching collage of reflections on how he changed from a budding teenage songwriter to an ostensible indie-rock icon still making melodies as he closes in on middle-age.

Heartworms is an understated and charming production of orchestral rock, surfy riffs cresting summery melodies and experimental streaks of reverb. It even includes a couple of just-about-danceable dashes of synth-heavy trips glowing with a glammy new-wave sound. The way Mercer sings throughout—the break in his voice, the curve in his lower register to the ache in his falsetto—is usually more interesting than what he’s singing about. He’s always sounded like the kind who gives his heart time to harden before poetically penning his regrets; the wounds never sound fresh.

But Heartworms glimpses something deeper than Mercer’s moods: his spirit. “Fantasy Island” is a stand out, half of it being a blunt verdict from a deep stare into the mirror, the other an ode to the special sanctuary that songwriting provided him. The song is also an excellent example of how one tastefully adorns a slower-tempo pop-rock song with electronic studio wizardry without plasticizing its emotions or chilling any of its warmth.

“Mildenhall” brings a subtle cha-cha beat to a folksy riff that winds its way around these celestial synth-chimes, while Mercer paints a picture of an awkward, lonely, and almost alienated teenage version of himself who blossomed, cheesy as it sounds, through the discovery of the right ‘80s rock records and a couple of chords on his dad’s guitar: “And that’s how we get to where we are now,” he sings in a seesaw melody.

“Half A Million” has immediate urgency with its chugging riff, pounding keys and low-growling bass, and Mercer matches its initial velocity with a punchy, rise-and-fall melody, pushing against how “there are half a million things that he’s supposed to be…” But when things get too deep, he sings, that’s when he reaches for his guitar. The songs of The Shins have provided emotional for a generation of former teenagers in the 2000s, but this album’s heartening revelation, however cliched it may read, is that these songs, Mercer’s songs, have always been his own sanctuary, as well.