Every culture and generation creates its own mythology, and for baby boomers or fans of classic rock music, Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes sessions from the summer and fall of 1967 have assumed an importance that rivals the mystique of the Ark of the Covenant or the unearthing of The Dead Sea Scrolls. As overstated as that may sound, Dylan’s Basement Tapes have already been the subject of two books and more articles than anyone would want to count, and prior to the release this month of The Basement Tapes Complete, the number of fan attempts to cull all of the sessions together in bootleg form has been equally impressive and intense. The only other unreleased music that has received close to the same amount of intense scrutiny and unofficial pressings as The Basement Tapes is The Beach Boys’ Smile and Jimi Hendrix’s unreleased albums, all of which have seen the light of day in recent years.

When the news began to trickle out that Dylan’s people were finally putting together a definitive set of The Basement Tapes using Garth Hudson’s original reels, his fans were understandably delighted. What they didn’t realize was that there was even bigger news coming down the pipe; Dylan’s publishers had discovered a drawer full of handwritten lyrics dating from the same period as the Basement Tapes recordings and sent an email to producer T Bone Burnett and asked him whether he’d “like to do anything with them.”

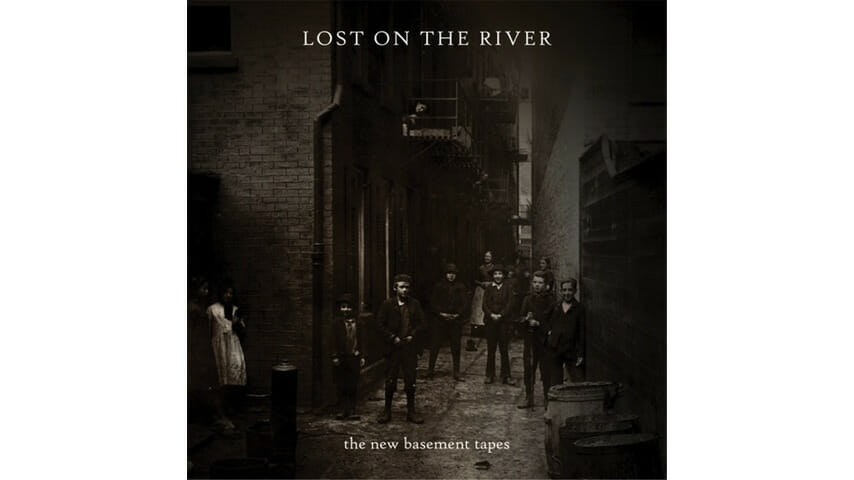

Once Burnett found out that the project had Dylan’s blessing, he agreed and contacted musicians he thought would be compatible with the spirit of Dylan’s original creation. He sent them each 16 lyric samples to work with. The invited musicians—Elvis Costello, Rhiannon Giddens, Taylor Goldsmith, Jim James and Marcus Mumford—were given some time to play with the lyrics before they met at Capitol Studios in Hollywood in March of this year. Some of the musicians were working with the same lyrics and had composed completely different melodies. Some of these melodies echoed Dylan and The Band’s style from that period, while others sounded like a blend between Dylan and his interpreter. Just before the sessions started, eight additional sets of lyrics were found, and everyone who had gathered contributed to giving these songs life. With so many diverse interpretations of lyrics and approaches to songwriting, Burnett wisely chose not to make the recording session into a competition, so he recorded everything and Lost On The River: The New Basement Tapes, complete with multiple versions of the same lyric, is the result.

Before getting into reviewing the individual performances on Lost On The River, it’s interesting to consider how difficult it must have been for the artists to approach this material. Using old lyrics from a legendary songwriter and having sympathetic contemporary musicians write music for and sing them isn’t a new idea. The Mermaid Avenue sessions with Billy Bragg and Wilco that explored unpublished Woody Guthrie lyrics through new recordings was the first project of this kind. Since then, there have been several other successful Guthrie lyric projects involving musicians from the worlds of rock, folk, country, bluegrass, punk and reggae that indicate a far more prolific and wide-ranging body of work than anyone could have imagined. The Lost Notebooks of Hank Williams that came out a few years ago—with an excellent new performance from Bob Dylan among others—is another example of a successful project of this kind. The only difference between these and Lost On The River is of course that Bob Dylan is still a living artist who regularly tours and produces new work. Neither Guthrie nor Williams were alive when Mermaid Avenue or The Lost Notebooks came out, so they were unable to offer input or complain. It must have been harder for Costello, Giddens and company to approach this work, knowing darned well that Bob Dylan would be listening.

The good news is that overall, Lost On The River is a lot of fun to listen to and the performances are at least as good as you’d expect them to be. It’s easy to feel the good will and the excitement that playing this music inspired in the recordings. It is a sound that can only be achieved when everyone is in the same room playing together with the understanding that any surprises, goofs or slips will be left intact as a way of embracing the original spirit of the Basement Tapes sessions. All of the artists seem to share an unspoken understanding that no one could touch the magic that Bob Dylan and The Band created in that long ago summer of ‘67, so they didn’t even try. Lost On The River is a joyful record, and everyone sounds like they had a lot of fun making it. And, for once T Bone Burnett seems to have been content to steer the proceedings without imposing his very recognizable production style on top of every recording. He’s been prolific and over the past few years his style has become just as identifiable as those of Phil Spector, Brian Eno or Daniel Lanois. The effect has been that on occasion he has overshadowed the artists he’s working with and saturated their work with his trademark sounds and effects. He maintains a light hand here, giving the artists lots of room to move around and interpret the music.

Good vibes seems to have been the order of the day from the beginning to the end of the Lost On The River sessions. The music industry is often about hard sell where every artist makes sure that his or her management promotes the hell out of everything they do, but Lost On The River is surprisingly different. The listening copy I received a few months ago had no credits whatsoever, and somehow that allowed me to take each performance at face value without dissecting who sang or played what. Considering the epic nature of the project and how it could all have devolved into ego battles, this was the right approach to take. Apparently, almost every version of every lyric that each artist wrote melodies for was recorded, and the multiple interpretations of the same basic song that are included on the deluxe edition of Lost On The River highlight how wonderfully creative the sessions were.

Some tracks like “Kansas City” as sung by Marcus Mumford follow the very simple blues structures favored by The Band during the original Basement Tapes sessions, while others like Giddens’ version of “Spanish Mary” hearken back to Dylan’s work from the early ‘60s when he was first enamored with the American folk traditions. Elvis Costello captures the world-weariness suggested by the title track with one of his best recordings in some time, while Giddens transforms the same lyric into a regretful, torchy lament that closes the album. Even Jim James’ voice—which can sometimes dominate with little more than a whisper—has been dialed down a few notches for his takes of “Down On The Bottom” and “Quick Like A Flash,” resulting in some of the most nuanced and impressive performances of his career.

Bob Dylan has always been a prolific artist who has thrown away more ideas than he has recorded, and projects like this invite people to wonder how many more drawers full of lyrics he has scattered all over the world. Once, I asked Nora Guthrie to tell me how many more good Woody lyrics were still out there, and she laughed at me. She said that she had no idea because Woody wrote constantly, kept many notebooks on the go and she confessed that they hadn’t all been opened, suggesting that Billy Bragg grabbed the closest one to him and never got much further—there was that much good stuff! Hopefully, that’s also true of Bob Dylan’s lyrics and Lost On The River is just the first of several albums like this.