Musicians often talk about the difference between slow thinking and fast thinking. Slow thinking is when you’re composing an instrumental or writing a song; it’s when you take your time to consider and reconsider each note, each phrase before fitting it in its place. Fast thinking is when you’re performing or improvising; that’s when you have to keep up with the pulse of the music and let the notes fly without any premeditation or second guessing.

Wayne Shorter, the masterful saxophonist who died Thursday at age 89, was the rare musician who excelled at both modes. He composed some of the most enduring jazz compositions of the second half of the 20th century: “Footprints,” “Ana Maria,” “Black Nile,” “Juju” and “Speak No Evil.” But he also recorded some of the most memorable solos of the period.

Both his slow thinking and his fast were marked by the same qualities: the lyricism of elegant melodies, the yearning of a never-ending quest and the sense of always discovering something new along the way. He explained this when I interviewed him in 1997, as he was embarking on a tour as an unaccompanied duo with keyboardist Herbie Hancock.

“We’re finding it’s a great adventure.” Shorter said. “You get out on stage, look around, and there’s no rhythm section behind you, and you realize, `Oh, it’s up to me now. I can’t rely on the beat to string the music together; I can’t just fall in line with the known; I have to go into the unknown.’

“We’re not throwing out anything like, ‘Here comes the killer chorus.’ You don’t have to do the ‘One, two, three, four, one, two, three, four’; you can change anything at a moment’s notice. The pulse can go slower and something on top of the pulse can go a thousand miles an hour. It seems to reflect what a human being is about. A thought can run through a person’s mind while he or she is standing still. A swan can look like it’s still on a lake while its feet are swimming like wild.”

Watch Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock play the Newport Jazz Fest in 2004:

Rock fans will know Shorter from his guest appearances on two classic tracks: his surging tenor sax solo on Steely Dan’s 1977 “Aja” and his dancing soprano sax solo on Joni Mitchell’s 1979 “The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines.” But jazz fans know him from his 64 years at the genre’s center of gravity. A musician is lucky if he or she joins one legendary band. Shorter joined four.

It began in 1959 when the 26-year-old Shorter completed perhaps the greatest of the many line-ups known as Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers. Playing with drummer Blakey, trumpeter Lee Morgan, pianist Bobby Timmons and bassist Jymie Merritt, the young saxophonist quickly established himself as a transformational figure. Most of the 14 albums he recorded with the Jazz Messengers included multiple compositions by Shorter, and his brawny tone on the tenor usually provided a tune’s peak moment.

Miles Davis noticed. After repeated attempts, he finally hired Shorter away from Blakey in 1964, thus creating the most famous Davis Quintet of all. Trumpeter Davis and saxophonist Shorter were joined by pianist Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams. The newest member of the group was soon writing a high proportion of the group’s material, including the title tracks for the albums E.S.P. and Nefertiti. The quintet began as an all-acoustic chamber group that was remaking jazz by freeing group improvisation from strict chord changes and metrical units.

“The music we did with Miles allowed a lot more control of each musician’s destiny,” Shorter told me. “You were on your own, and knowing that, we joined together. You’re not thinking on your own, you’re just part of the train being pulled by the locomotive. We were on the cutting edge of musical expression, stepping into unknown territory. What does it feel like to play without any harmony? You’re playing with the kind of stuff that the record companies say won’t work, that the audience won’t get it, Americans’ attention span is very short. They’re downgrading the public in that sense.”

Watch Wayne Shorter play the Newport Jazz Fest in 2001:

This quintet helped Davis gradually incorporate electric instruments and rock ‘n’ funk vocabulary into the music. This led the brilliant transitional album, 1969’s In a Silent Way, and the 1970 best seller, Bitches Brew. Hancock, Carter and Williams had left the band by then, leaving Davis and Shorter to tour with a new group that included Chick Corea, Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette.

In 1971, Shorter and Joe Zawinul, the keyboardist who wrote and played on the title track for In a Silent Way, co-founded the third hugely consequential band of Shorter’s career: Weather Report. After several personnel changes, the band’s most famous line-up crystalized: Shorter, Zawinul, bassist Jaco Pastorius and drummer Peter Erskine. Unlike most fusion bands of the time, who considered compositions as little more than a vehicle for jamming, Weather Report offered pieces with memorable themes and sturdy architecture. Zawinul wrote the majority, but Shorter contributed such standouts as “Palladium” and “Mysterious Traveler.”

During the Weather Report years, Shorter continued to record the solo albums he’d begun during his first year with Blakey. Highlights include 1965’s Speak No Evil, 1966’s The All Seeing Eye and 1967’s Adam’s Apple. Especially noteworthy is 1974’s Native Dancer, a collaboration with singer Milton Nascimento and other Brazilian musicians. It’s not only a landmark encounter between North American and South American artists but also a recording of mesmerizing, understated romance.

“Millions of people have heard the music from Native Dancer,” Shorter told me, “even though only 50,000 heard it when it came out. People respond to it, because within that music is the DNA for existing the way we do now. You don’t hear that kind of music every day. My wife Ana Maria and her sister made the telephone calls to Brazil, and we did that album in 10 days. The way it came out it has a sound and a sheen to it unlike any other album, including all the other Brazilian albums.”

By the time the ’70s turned into the ’80s, however, Shorter’s creativity seemed to be dwindling. He was contributing fewer compositions to Weather Report, and his solo albums squandered promising compositions on heavy-handed fusion arrangements, gimmicky synth sounds and clumsy rhythm sections. His old comrades were so worried that DeJohnette actually composed a song that asked, “Where or Wayne?”

The turnaround began in 1997 with the unaccompanied acoustic-duo album with Hancock, 1+1, and the tour that followed. By stripping away the other instruments, the cheesy synthesizers and burden of the bop and post-bop past, Shorter was able to rediscover the core of his art.

“We want to get away from that old formula–I play, then you play; I talk, then you talk,” Shorter explained that year. “If we just play the melody from Herbie’s `Maiden Voyage’ and then solo on the harmonic changes, we’re doing what any two people could do. We’d be doing the known and not venturing into the unknown. What we want to create is a sense of instantaneous cause and effect, where the effect doesn’t happen after the cause, but they co-exist simultaneously, one in the other. I don’t want to wait while Herbie takes a solo and then I can respond to it in my solo; I want to respond while he’s creating.”

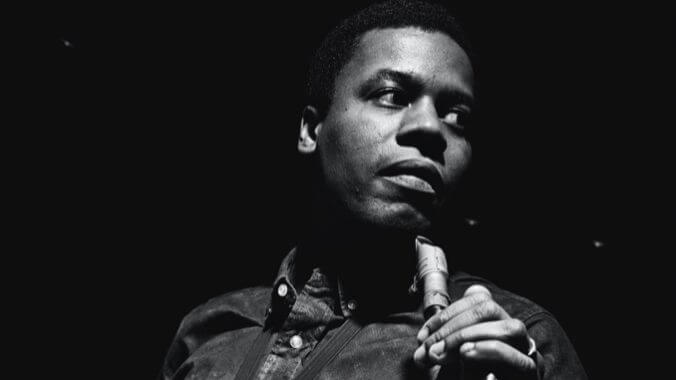

Wayne Shorter in 2012 (Photo by Robert Ashcroft, Courtesy of Blue Note Records)

That breakthrough led in 2000 to the saxophonist’s final legendary band: the Wayne Shorter Quartet, featuring pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci and drummer Brian Blade. He extended the minimalism of his duo project to the quartet. He played sparingly, holding back for the right moment to enter with just the right phrase to turn the music in a new direction. The group is best represented by the 2005 album Beyond the Sound Barrier and 2013’s Without a Net, each presenting reawakened older compositions and surprising new pieces.

In recent years, after retiring the quartet in 2018, Shorter collaborated with bassist Esperanza Spalding, both on a 2018 opera called Iphigenia, and on an album, Live in Detroit, which won a Grammy Award on February 5, just 25 days before the saxophonist’s death. He had already lost his father, daughter and second wife to tragic, premature deaths, but he used his own interpretation of Buddhism to sustain his equanimity and creativity through it all.

“I don’t hear music just to hear it,” he said. “If I feel a need to hear it to jolt me back to a place of genuine intent, I have a vast library to call on. Music is always speaking to me. I’m finding out what music is for. It’s not just to get a kick from, not just to show off some acrobatics, not to arrogantly give something to the world. The music I’m working on now is a link to eternity, so death is nothing.”