Variations on the Death of Castro

Why are Americans on the right and left reacting so differently to Fidel Castro's death?

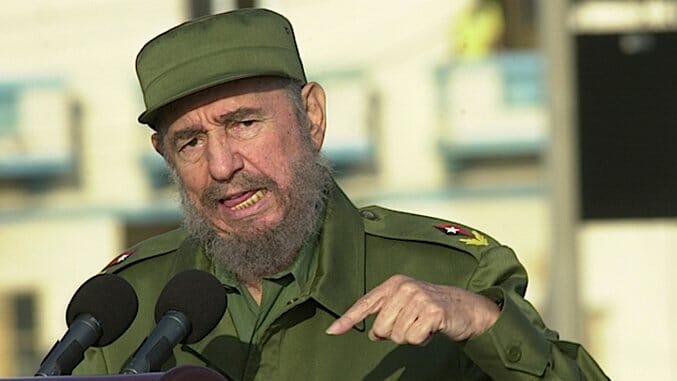

Photo by Jorge Rey/Getty Politics Features Fidel Castro

There’s a great play by David Ives called Variations on the Death of Trotsky. If you haven’t seen or read it, it’s about Leon Trotsky’s death-by-pickaxe-to-the-head, told in eight different ways. It’s a nice piece of postmodern theater, insightful in its embrace of absurdity. The main takeaway is: there are a lot of ways to think about death and even more ways to dramatize it, especially when it comes to political figures. Ives proved this with Trotsky’s demise. Twitter, politicians and the media are proving it right now with Castro’s. Not to mention, the way we talk and think about Castro can show us something about the way we talk and think about everything else.

The wide range of reactions to his death should be proof enough of the Cuban leader’s complexity. Justin Trudeau fawned over him as a friend of his father’s and Cuba’s “longest-serving president” in his statement. At least we got #TrudeauEulogies out of it. Green Party presidential candidate Dr. Jill Stein echoed the Canadian Prime Minister’s laudatory tone on Twitter. Barack Obama offered a measured, cautious take on it all, although his pursuit of nuance drew the justified ire of Cuban American Senators Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz. President-Elect Trump started out with the obvious, went shortly thereafter for the jugular, and is now making ominous statements about the future of Cuban-American relations.

In his death and his life, the Cuban leader stayed in the Western imagination as the sort of person who’d be in Dante’s Hell but perhaps in a better circle than some of history’s other villains. Anyone would agree he ranks on the “better” end of a spectrum of brutal despotism than Mao, Stalin and Hitler but, come on, we’re talking about a spectrum of brutal despotism here. He was the sort of person you’d always need to offer qualification for praising in any way—a quick “of course, the bad things he did were really bad” to keep people from jumping down your throat. Even with qualifications, they still would have a right to do so.

Castro’s brazen (think Trudeau) or wary (think Bernie Sanders) appraisers tend to reference nationalized Cuban health care as evidence the guy wasn’t all bad. There’s merit to this. Cuba actually beats out the United States when it comes to preventing infant mortality, it has a life expectancy rate similar to that of most developed nations and there are more doctors per people than in most developed countries. In fact, Cuban doctors are one of the country’s main exports to the world at large.

It shouldn’t really come as a surprise these doctors are leaving though, considering cab drivers are paid more than them. Not to mention, the health care system as a whole took a bit of a dive after the Soviet union collapsed in 1991 and Cuba stopped receiving subsidies from the USSR. This is also one of many ways in which the USA’s embargoes on and overall policies toward Cuba ended up affecting ordinary Cubans in an attempt to punish Castro’s authoritarian government.

Education was also a priority for Castro. Cuba has the second-highest literacy rate in the world and spends more on education (adjusted for GDP) than the U.S. and the U.K. combined. Unfortunately, despite all this, teachers are fired for dissenting from official party doctrine and students are kept from opportunities unless they stay in line with the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution.

There is also the blatant case against Castro. After coming to power, he threw homosexuals, Jehovah Witnesses and conscientious objectors into work camps called Military Units to Aid Production. He ultimately apologized for this. Under his rule, upwards of three thousand people were put to death by firing squad while well over a thousand were killed extrajudicially. While the nationalized economy still provides for its people in some ways, Cuba remains decidedly poorer than it needs to be.

Given all this, Castro can become all things to all people. In other words, Bernie Sanders applauding the health care and education system is just as logically valid as Marco Rubio being disgusted with anything short of outright condemnation for his worst human rights violations is morally valid. Authoritarians usually end up doing at least a few good things in the midst of their heinous depravity and records of oppression.

Ultimately, these “variations” on the death of Castro reveal something deeper about our American landscape and the characters populating it in 2016. Condemning the far-off authoritarian is easy, paying lip service to America’s supposed moral superiority is even easier. What’s hard is doing so in a way that doesn’t backfire and ultimately become a critique of the very nation-state we’re living in too. There is one candidate losing all our elections lately and it’s American integrity.

Much has been made of Trump possibly walking into the Oval Office and doing his best to rule like a Diet Castro. He’ll have an easier time doing this than he should. He’ll inherit an extrajudicial drone-strike and imprisonment program, a mass surveillance apparatus, and an ability to wage war in such a way as to make Castro’s death toll look like child’s play. I think people like Rubio and Cruz are justified in their condemnation of Castro and any praise he may get. I just hope they and people of their ilk will be willing to call our own government to account too and not just when it’s run by someone of their opposing party.

The same goes for any well-meaning liberals celebrating Castro’s educational and medical reforms while demonizing Trump. Calling out Trump with any ethical legitimacy means there should be a fearlessness in calling out Castro too. We can’t be partisan in our outright condemnations of authoritarianism. For all of President Obama’s charms, the facts indicate he’s leaving Trump with even more ammo to rule as an authoritarian than he would’ve had at the end of the Bush Administration.

Castro is dead and so is most of our moral high ground over him. We’ve all become so wrapped up in our own echo chambers that weighing in on Castro makes us all look like hypocrites in one way or another. When we talk about Castro, we talk about everything. Political criticism has to start with our own beliefs, our own leaders, our own country before it can hold much moral authority or legitimacy in a global sense. Otherwise, we’re just a country with some decent parts in the midst of a ton of corruption. Sound familiar?