The Health Insurance Death Spiral—What it is, and Why it Matters Under the AHCA

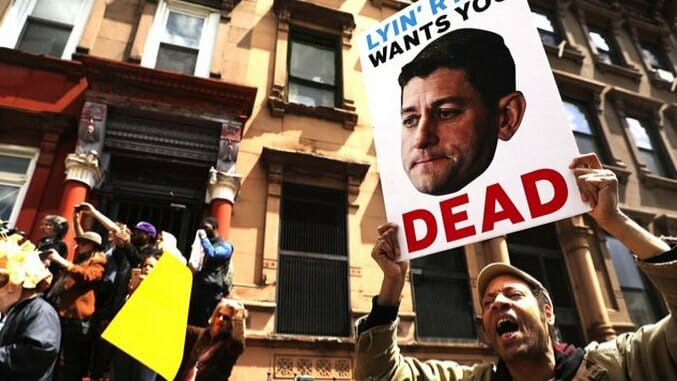

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Politics Features Health Care

Yesterday, the Congressional Budget Office released their long-awaited analysis of the new-and-unimproved American Health Care Act that passed the House earlier this month, and a few things became clear. Well, one big thing became clear—as Paste’s Jacob Weindling found, it’s still a disaster. From raising premiums on seniors by astronomical amounts to throwing 23 million Americans off insurance to “eviscerating” protection for pre-existing conditions to giving states the option of slashing coverage for mental health, substance abuse, and maternity care, it’s one of the crueler pieces of legislation ever considered in American history.

Today, I want to narrow the focus—it’s impossible to consider every atrocity at once—and discuss a very specific and lesser known consequence that will almost certainly strike a fatal blow at America’s sickest citizens, should the plan pass the Senate and reach implementation. I’m talking about the so-called “Death Spiral”), which poses an incredible danger for anyone suffering from a serious, expensive illness, and could make it practically impossible for these people to purchase affordable insurance.

What is the Death Spiral?

First, I want to outline the theory of the death spiral. Simplified slightly, here’s what it entails:

1. Let’s say, for instance, that you buy a health insurance policy. Under the Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare, there are “community rating” requirements which essentially mandate that insurance companies keep both healthy and sick people together in the same “pools,” and charge them similar rates. However, in the absence of such a mandate, an insurance company could charge rates based on the overall health of the group.

2. Once a group’s enrollment is closed, certain members of that group will become increasingly sick over time. As such, the amount they spend on health care increases. In response, the insurance company increases premiums, deductibles, and other costs for the entire group, in order to cover the new costs.

3. The healthy people in the group, not wanting to pay higher rates to offset the new costs incurred by the unhealthy people, opt out of the group. Maybe they seek a new group, at something close to the original rates, maybe they’re advised to do so by a financial planner, and maybe the new group is advertised to them by the insurance company itself.

4. Unhealthy people, on the other hand, cannot qualify for the new groups because of their new conditions. They are forced to remain exactly where they are. With the healthy people fleeing, average costs for the original group continue to rise as those who remain spend more on health care.

5. Increasingly, healthy or even moderately unhealthy people continue to flee the group, seeking cheaper prices elsewhere. Costs in the original group rise with each new adjustment. Finally, only the most unhealthy people remain, and their prices increase exponentially until insurance becomes unaffordable.

6. Finally, faced with the new unaffordable costs, the group expires. The very unhealthy people who have lost insurance are left in the lurch—either they won’t qualify for any new insurance at all, or the premiums would be so expensive as to be prohibitive.

As noted, there was protection against this death spiral in the ACA—by mandating that companies keep poor and sick people in the same group and issue community ratings, rather than set prices based on collective health status, the program cut off the death spiral before it could begin. Additionally, the individual mandate puts a tax penalty on those healthy individuals who may opt out of insurance totally, and thereby put a higher financial burden on those who remain.

What Changes With the AHCA?

Two weeks before the new version of the bill passed the House, the Center on Budget and Priority Policies laid out exactly what could happen to erase these protections. There are two waivers that become open to individual states within the new plans, but the relevant one here—insisted upon by the Freedom Caucus—is a waiver of the current community rating requirements.

As the CBPP points out, these waivers are limited, at least on paper, by two criteria:

1. A program must be in place for those with pre-existing conditions.

2. Companies could only “underwrite” its policy holders—that is, base their premiums off of their health status—if the person could not demonstrate continuous coverage (which means coverage for all but 63 days of the 12 previous months, which would cut out roughly one-third of all people with pre-existing conditions anyway).

However, neither limit would actually work to prevent abuse, and the CBPP lays out exactly why:

Moreover, in practice, the limitation almost certainly wouldn’t bind: people with pre-existing conditions who maintained continuous coverage would still end up being charged more, often far more, as a result of the waiver — because they would end up being pooled primarily with sick people rather than with a mix of sick and healthy people, as at present.

Here’s why this would occur…for people who are healthy and low cost, medical underwriting would result in lower premiums than if they were part of a “community rated” pool that also includes sicker, higher-cost individuals. As a result, most healthy people who were continuously insured would choose (and be advised by insurers and brokers) not to submit proof of continuous coverage, so that they could obtain lower premiums by being medically underwritten. (Exacerbating this problem, some healthier-than-average people who have been enrolled in individual market plans could decide to leave the market entirely, as they would no longer be subject to the individual mandate to pay a penalty if they are uninsured.)

The result is that the people choosing to provide proof of continuous coverage would largely be those who are sicker than average. And to avoid losing money, insurers would have to raise their premiums substantially for these people. The bottom line is that coverage would become much less affordable for people who have pre-existing conditions and are in poor health, whether or not they maintained continuous coverage, because community rating would essentially exist in name only: sick people would mostly be pooled with other sick people.

Moreover, this problem could grow worse over time. Once community-rated plans were priced for a sicker-than-average pool of enrollees, new applicants with moderately expensive conditions like hypertension often would find that they could obtain lower premiums by undergoing medical underwriting than by being pooled with people with much costlier conditions like cancer.

That language should sound familiar. Essentially, the AHCA provides the perfect conditions for the death spiral to flourish.

What the CBO Said

The predictions of a progressive think tank like the CBPP are one thing, but what does the actual CBO say?

In the 41-page report released yesterday, the conclusions are almost exactly the same. The relevant passage:

A second type of waiver would allow insurers to set premiums on the basis of an individual’s health status if the person had not demonstrated continuous coverage; that is, the waiver would eliminate the requirement for what is termed community rating for premiums charged to such people. CBO and JCT anticipate that most healthy people applying for insurance in the nongroup market in those states would be able to choose between premiums based on their own expected health care costs (medically underwritten premiums) and premiums based on the average health care costs for people who share the same age and smoking status and who reside in the same geographic area (community-rated premiums). By choosing the former, people who are healthier than average would be able to purchase nongroup insurance with relatively low premiums.

CBO and JCT expect that, as a consequence, the waivers in those states would have another effect: Community-rated premiums would rise over time, and people who are less healthy (including those with preexisting or newly acquired medical conditions) would ultimately be unable to purchase comprehensive nongroup health insurance at premiums comparable to those under current law, if they could purchase it at all—despite the additional funding that would be available under H.R. 1628 to help reduce premiums. As a result, the nongroup markets in those states would become unstable for people with higher-than-average expected health care costs. That instability would cause some people who would have been insured in the nongroup market under current law to be uninsured.

The CBO estimates that 1/6th of the U.S. population lives in states that would accept the community ratings waiver—an estimate that seems conservative, considering that Republicans control 33 state governorships and 32 state legislatures—and in these places, “less healthy people would face extremely high premiums,” and that said premiums would increase “rapidly.”

At that point, for someone with cancer, to use a common example, there’s a choice—buy health insurance, go into serious debt, and attempt to stay alive, or forgo health insurance and let the disease run its course.

This choice, between bankruptcy and death, is immoral to its core, and the so-called “death spiral” is aptly named, as it can only lead to one outcome. And what does it say about a nation that would pass such a law, and impose such cruel, punitive measures on its citizens? Perhaps it says that the death spiral doesn’t apply just to America’s sick; perhaps when we’ve reached such a low point in our collective morality, a similar destiny awaits the country at large.