Trump’s Justice Department Can Now Seize Your Property

Paying Down the Law

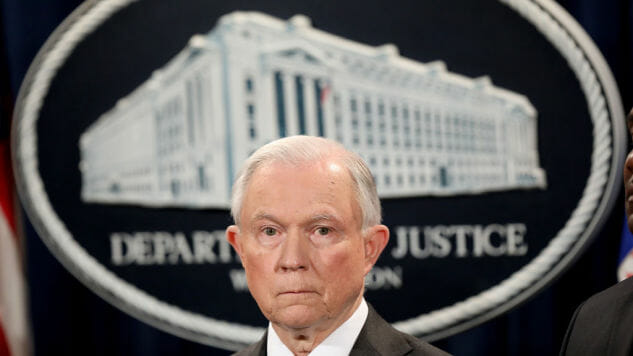

Win McNamee / Getty Politics Features Jeff Sessions

Civil forfeiture, the seizure of property by the government, is being used unjustly and unethically. Property is not sacred, but the well-being of my fellow citizens is. When forfeiture is used against the meek, it becomes everyone’s business. Asset-grabbing is part of the grotesque process where law enforcement parasites off the population it is there to protect. As the forfeiture expert Christopher Ingraham wrote in the Post:

Under civil forfeiture, the burden of proof is on the property owner to prove their innocence to get their stuff back. This turns the common criminal-law principle on its head: When it comes to civil forfeiture, you are guilty until proven innocent.

“Stop and seize” really took off after September 11th, and the government never looked back. Why would they? Money for nothing and checks for free. Since Ingraham’s original article on the topic, about $2.5 billion in cash has been grabbed on the highway. And that’s not considering everywhere else forfeiture predominates.

THE VAMPIRE RETURNS

Recently, under Trump, forfeiture has roared back to life. According to Ingraham, the Sessions Department of Justice just turned the ”$65 million asset forfeiture spigot back on”:

The Justice Department announced on Wednesday that it will be restarting a federal asset forfeiture program that had been shut down by the previous administration.

JUST IN: DOJ new asset forfeiture policy – police can seize property from people not charged w/crime even in states where it’s been banned. pic.twitter.com/P8K0g80m4E

— Paula Reid (@PaulaReidCBS) July 19, 2017

Sessions knows a profit opportunity when he sees one. It was a return to form for the Department of Justice. Until recently, the blatant money-grubbing from federal and local law enforcement was much more obvious. Ingraham explained:

Known as “adoptive forfeiture,” the program — which gives police departments greater leeway to seize property of those suspected of a crime, even if they’re never charged with or convicted of one — was a significant source of revenue for local law enforcement. In the 12 months before Attorney General Eric Holder shut down the program in 2015, state and local authorities took in $65 million that they shared with federal agencies, according to an analysis of federal data by the Institute for Justice, a public interest law firm that represents forfeiture defendants. While adoptive forfeitures amount to just a small percentage of the annual multi-billion dollar forfeiture haul, they’ve come under harsh criticism for allowing local authorities to sidestep state guidelines and instead take cash and property under much more permissive federal rules.

Ingraham elaborates on the problem: thirteen states have statues which mandate conviction before assets are seized. He writes:

Under federal guidelines, the state and local agencies making adoptive seizures are entitled to up to 80 percent of the proceeds, while federal agencies would receive at least a 20 percent cut. The median value of those seizures was about $9,000, not exactly indicative of major drug trafficking operations. Some of the seizures were as low as a few hundred dollars, including $107 taken by Kanakee, Ill., authorities on March 12, 2014. That money was turned over to the DEA, which is entitled to keep $21.40 of it, with the remaining $85.60 to be returned to Kanakee police.

NICKEL AND DIMING

Who gets the short end of the seizing stick? Why, those who can least afford to contest it:

These numbers comport with numerous other investigations that have found that forfeiture efforts tend to target poor neighborhoods. Between 2012 and 2017, for instance, the median value of assets seized by Cook County police was just over $1,000. A 2015 ACLU analysis of cash forfeitures in Philadelphia turned up a median value of $192.

“The small dollar values often at stake,” Ingraham writes, “undercut forfeiture defenders’ claims that the practice is necessary to disrupt major criminal organizations.”

According to C.J. Ciaramella, poor folk are regularly hit by forfeiture:

Police in Chicago and its surrounding suburbs seized $150 million over the past five years. Those seizures were heaviest in low-income neighborhoods, according to public records. Law enforcement in Cook County, which includes Chicago, seized items from residents ranging from a cashier’s check for 34 cents to a 2010 Rolls Royce Ghost with an estimated value of more than $200,000. They also seized Xbox controllers, televisions, nunchucks, 12 cans of peas, a pair of rhinestone cufflinks, and a bayonet.

Sarah Stillman, writing for the New Yorker, notes

Yet only a small portion of state and local forfeiture cases target powerful entities. “There’s this myth that they’re cracking down on drug cartels and kingpins,” Lee McGrath, of the Institute for Justice, who recently co-wrote a paper on Georgia’s aggressive use of forfeiture, says. “In reality, it’s small amounts, where people aren’t entitled to a public defender, and can’t afford a lawyer, and the only rational response is to walk away from your property, because of the infeasibility of getting your money back.” In 2011, he reports, fifty-eight local, county, and statewide police forces in Georgia brought in $2.76 million in forfeitures; more than half the items taken were worth less than six hundred and fifty dollars. With minimal oversight, police can then spend nearly all those proceeds, often without reporting where the money has gone. “When you allow the profit incentive, that’s when you start getting problems,” Porter said. “It’s like the difference between serving in the Army and working for Blackwater.”

A Justice Department study said that about 87 percent of their seizures required no criminal charges. You could write a ballad about how clumsy the law’s ledger-bolstering actions have been.

BREAKING EVEN

Co-opting public assets is not a new proposition. The reason for the Holder-era reversal was the amount of bad press that profit-hungry John Law got during the Obama Years.

We saw it (and see it) in Ferguson and other American cities, where the police departments pimp out the ordinary people to fatten the departmental wallet. It happens in Florida and Michigan, Pennsylvania and Virginia, Alabama, Missouri, and North Carolina.

Martinez, Meeks, and Lavandera reported for CNN in 2015:

Just about every branch of Ferguson government — police, municipal court, city hall — participated in “unlawful” targeting of African-American residents such as Hoskin for tickets and fines, the Justice Department concluded this week. The millions of dollars in fines and fees paid by black residents served an ultimate goal of satisfying “revenue rather than public safety needs,” the Justice Department found.

There was ”’Awesome!’ excitement about revenues,” according to a report by the Obama-era Justice Department:

The Justice Department’s report details how Ferguson operated a vertically integrated system — from street cop to court clerk to judge to city administration to city council — to raise revenue for the city budget through increased ticketing and fining. Ferguson’s budget increases were so sizable that city officials exhorted police and court staff to levy more and more fines and tickets against violators, who turned out to be largely African-American, the Justice Department said. The demands for revenue were so intense that the police department had “little concern with how officers do this,” even disciplining officers who failed to issue an average of 28 tickets a month, the Justice Department report said. Officers competed “to see who could issue the largest number of citations during a single stop,” the Justice Department said. One apparent winner was an officer who issued 14 tickets at a single encounter, according to the federal investigation report.

Gwynn Guilford, writing for QZ, noticed the same effect:

Ferguson’s economy steadily withered over the last decade, as did its population. Yet even as the number of adult residents fell 11% between 2010 and 2013, fines collected by the city’s court system surged 85%, hitting $2.6 million last year. … In fact, arresting people for minor violations is exactly the point, as Brendan Roediger, professor at the Saint Louis University School of Law and supervisor of a local civil advocacy clinic, told Governing magazine in its must-read piece. “They don’t want to actually incarcerate people because it costs money, so they fine them,” Roediger said, adding that Ferguson’s court sometimes hears as many as 300 cases per hour.

Terrence McCoy, writing for the Post, told the story of the ghoulish collection agencies running many American police departments:

This, as the Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates pointed out on Twitter, is “plunder made legal” and “Municipal employees in Ferguson report sound more like shareholders. Gangsters.” Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. called it a system “primed for maximizing revenue” — one that now basically serves as a “collection agency” instead of “a law enforcement entity focused primarily on maintaining public safety.” “The new Department of Justice report depicts a system in Ferguson that is much closer to a racket aimed at squeezing revenue out of its population than a properly working democracy,” wrote George Washington University political scientist Henry Farrell … As described in the report, Farrell and others pointed out, Ferguson is reminiscent of medieval Europe, when gangster governments collected “tribute” and bamboozled the subject population at every turn.

Then (as now) for-profit law enforcement system rules everywhere, what Human Rights Watch has deemed the “Offender-Funded Business Model.” In post-industrial capitalism, where everything is outsourced, why not outsource the running of departments to the offender? This model rules the roost in probation, in court, in everything.

Time after time, the goods of innocent people have been grabbed by overzealous law enforcement in the pursuit of ambiguous ends and little-defined goals. Where can the victims turn? What authority do they petition? Asset grabbing, when unwarranted, is a body blow to people of small property and little power. It is part of the encroaching militarization and armoring of law enforcement against the populace. It was done during the hysteria of the Eighties and Nineties, and the powers of John Law were augmented during our unjust drug war. The world of terrorism is forfeiture’s golden age. It is long past time to dismantle the hungry hands of justice. We get the law enforcement we pay for. Literally. Crime may not pay, but seizure certainly does.