For Politicians, Raising Money Is Easy. But Spending It Smartly Requires an Actual Ideology.

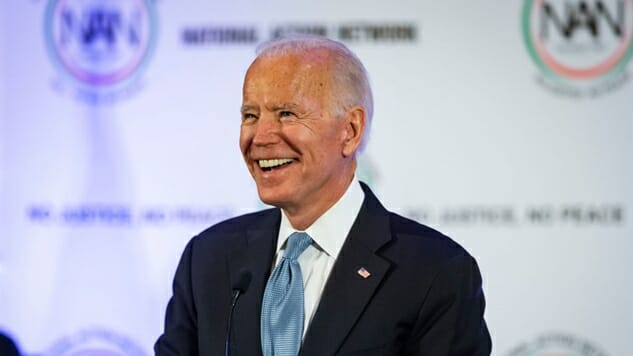

Photo courtesy of Getty Politics Features Money in Politics

In politics, raising money is not the hard part. When all’s said and all’s done, the tougher game is deciding what to do with the money.

It is simpler and quicker to raise money effectively than it is to spend it well.

By spend it well, I mean using money for 1) effective ads on behalf of 2) good candidates, for the purpose of 3) popular, winning ideas.

If there was a formula for spending money well, those of us in the American political class would have figured it out by now. Despite two centuries of experience, in every election cycle we see candidates with vast war-chests running tone-deaf ads for unpopular stances, and they barely scrape by on election day.

David Broockman and Joshua Kalla say so in Vox:

There’s a refrain we hear about political campaigns every election cycle: “this year, campaigns waged an unprecedented ground game, having a face-to-face conversation with almost every single voter.” Baloney. As academics who study campaigns, we hear this claim all the time. But we also know it’s important to investigate whether data backs it up. We did. And it doesn’t.

If politics was a business, who would invest in it? In 2012, the Romney Presidential Campaign’s final fundraising tally was $1.019 billion. Do you see anyone teaching his campaign at Wharton?

Politics is not a business, nor should it be. Political campaigns and parties can be run by business people, but they are not commercial enterprises. Let’s put our fashionable pedantic witticisms about money-in-politics aside. Political organizations are about pushing the commonwealth in some direction. Even if you’re a complete cynic, and think parties solely exist to trade money for influence, my question remains: Why is it so challenging to spend money well?

Parties and candidates raise funds by promising to beat the adversary, and to affect policy. That’s the issue at hand. The question on the table is why the standard of effectiveness is so low.

Electoral victory is about getting voters to come to the polls, as many as possible. Now, how do you do that? How do you decide how to spend the money, and what to spend it on? Polling alone will not suffice. If surveys were the answer, then every Hollywood film would be a blockbuster, and Nate Silver would never have been mocked online.

Clearly, numbers are not the secret, as the lottery-ticket fatalist said to his favorite gas-store clerk. Judgment is required for all three stages I listed above. Learning judgment is harder than picking up fundraising. Judgment requires correct observation, and correct weighing. The reason effective spending is difficult is because, typically, the people who spend the money cannot see clearly and cannot weigh well.

Why can’t they see clearly? Why can’t they reckon rightly? Because, I think, they are afraid of ideas. They are anxious about having identifiable positions on any issue.

These people believe they are rational, and that rationality comes first in politics. Neither of these statements are true. As modern cognitive science tells us, reason and feelings do not exist separately. Reason is a tool we use to make choices, and it is a useful one. But it’s just a tool. Without preferences, without feelings, you have no reason to prefer one option over the other. You cannot make sense of the data coming at you, and your relationship to that data.

Virginia Hughes wrote a story for National Geographic titled “Emotion Is Not the Enemy of Reason.” She noted that:

The idea that emotion impedes logic is pervasive and wrong … Consider neuroscientist Antonio Damasio’s famous patient “Elliot,” a businessman who lost part of his brain’s frontal lobe while having surgery to remove a tumor. After the surgery Elliot still had a very high IQ, but he was incapable of making decisions and was totally disengaged with the world. “I never saw a tinge of emotion in my many hours of conversation with him: no sadness, no impatience, no frustration,” Damasio wrote in Descartes’ Error. Elliot’s brain could no longer connect reason and emotion, leaving his marriage and professional life in ruin.

There have been lots of brain-imaging studies since then, writes Hughes, showing neural connections between reason and emotion. “It’s true,” she wrote, “that emotions can bias our thinking.”

What’s not true is that the best thinking comes from a lack of emotion. “Emotion helps us screen, organize and prioritize the information that bombards us,” Bandes and Salerno write. “It influences what information we find salient, relevant, convincing or memorable.”

In politics, without a set of beliefs, you cannot make value judgments. You cannot weigh alternatives. Without beliefs, you cannot make sacrifices, or justify making them. Bernie Sanders just gave a speech where he defended democratic socialism. There are excellent, rational reasons for making that choice. But would any politician have even dared such a risk without long-held beliefs? Doubtful.

So: raising money is not the hard part. The hard part is having an ideology.

You can get by in politics without beliefs.

Parties do. Candidates do.

Raising money, after all, does not take an ideology. It merely takes organization, and salesmanship, and relationships. The two parties are fundraising machines. You need those crucial monies to keep the crucial lights on during the crucial days of the year, which are all of the days. Specifically, to raise money, you need to appeal to:

—A few very wealthy people

—A larger group of pretty wealthy people

—A lot of of non-wealthy people.

It’s best if you can have the whole trio going for you, of course. To get all three of these groups, you have to make your party tent as wide as possible. This suits the people I mentioned above, the people who dislike ideology. In each party, there are stances the parties can’t compromise on. If you can’t compromise on the key planks, then you soft-pedal them. You don’t talk about them unless you have to. When you talk at all, you talk big-tent. Talking big-tent means using generic principles, for generic causes, with generic feeling. Again, you avoid ideology.

What is true of parties is also true of politicians. You can be a politician without having an ideology. The people who are very successful in politics usually have twenty or so separate talents. After a lifetime of being involved in politics, I have compiled a list of them. I’ve even ranked the required skills in order of importance:

1. Counting.

2. Horsetrading, negotiation.

3. Skill in private conversation.

4. Skill in making speeches.

5. Reading a room.

6. Reading individuals: guessing correctly at motives, desires, fears.

7. Reading the public.

8. Charm.

9. Ability to manage emotions, stress.

10. Timing.

11. The ability to sell.

12. Improvisational ability.

13. Some skill at guessing the future.

14. A sense of urgency.

15. The ability to hold your liquor, to endure mediocre food.

16. Photographing well.

17. The ability to recruit.

18. Skill at organization.

19. Smiling.

20. The ability to shake hands thousands of times.

If you have all twenty, you may succeed. But if you lack cash, you will not get out of the gate. No matter where your talents lie, coin is the golden key to unlock every door. You’d be surprised how long you could get by on just money.

So, no, fundraising and politicking do not require ideology.

But spending money well does. Spending well requires judgment, which requires priorities and preferences, which requires ideology. There’s a saying in drama class: “Acting is about making great choices.” Well, I know another trade that also requires choices.

If you are going to do this thing we call politics, you must have a ground floor. There must be a true north somewhere in your soul. I want to be clear: having an ideological backbone is not just a matter of morality. It is the foundation for being effective at any level of politics—but especially in campaigns.

According to linguists, without language, human beings would literally be unable to think. Ideas work the same way in politics. Without ideology, you can fund-raise, and you can survive, but you cannot thrive. Without an ideology—even a very loose one, like “Peace is always good”—you will squander your time and burn your money in predictable, anxiety-ridden reactions. And somewhere out there will be an opponent who does have beliefs. And they’ll be waiting.

Without an operating system, without a mission—without what George H. W. Bush famously called “the vision thing”—you are not really doing politics. You are doing fundraising with occasional tweets. Without beliefs, without commitments that are painful to break, you will never be able to make hard choices, to take risks; you will never be willing to turn down the very nice people who want you to, ah, keep things exactly as they are. You will never be able to overcome the fear:

Then Biden repeated his earlier remarks that he didn’t want to “demonize” the wealthy and added that, though “income inequality” is a problem that must be addressed, under his presidency, “no one’s standard of living will change, nothing will fundamentally change.” He went on: “I need you very badly. I hope if I win this nomination, I won’t let you down.”

Money is a number on a page. Money is not preference. People have preferences; people think, and act, and make choices. People are effective. Money is the fuel. It is not the fire. Money talks. And that’s all it ever does, or will ever do.