YOU ARE THE BOUNCERS, I AM THE COOLER

The greatness of the film Road House is that its bounty is an inexhaustible as the sea, but greater still than the sea, because it never killed a Titanic or allowed Iggy Azalea to pass over it to America. Unlike the briny traitor ocean, Road House has not drowned us or fed us fish, but instead taught men and women how to live. I could write an entire essay about Dalton’s deep statement that “Pain don’t hurt.” In his play “Total Eclipse” Chris Hampton has the French teen poet Rimbaud say that “The only unbearable thing is that nothing is unbearable.” The Stoics believed that pain only hurts if we tell ourselves it is unreasonable. With one huge, echoing voice, history shouts on the side of Dalton.

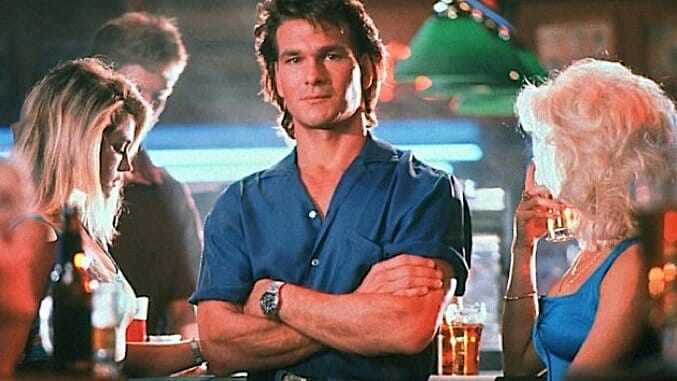

You ask, “Jason, who is this Dalton you speak of?” I roll my eyes, fall back onto my back, kick the air with mad violence—oh, friends. Can you ask what the sun is, or fire, or the terrible secrets of Tek War, and not receive the same reaction? James Dalton is the lead character of the action thriller 1989 movie/human panacea Road House, played by Patrick Swayze of dance/cowboy fame. Here, in his greatest role, he plays an NYU Philosophy grad who works as a “cooler”—this is like calling Moses a weatherman—with an exotic, unspoken past, who is invited to a hellpit of a country bar, The Double Deuce, in Jasper, Missouri. Frank Tilghman (Kevin Tighe), the owner of the “establishment” wants to bankroll the bar’s renovation, and lift its image.

But Jasper, it turns out, is a Hobbesian gangstomp of a town, a real war of all against all. So, logically, the first step in the road to nightclub redemption is to call in, what — an army? A team of mercs? No. He asks for one man. Dalton. A cooler, a gentleman Zen warrior who will, as the name suggests, “cool down” the hot tempers at this raving goon hole. And so Dalton arrives. His every punch is a poem, his every line is a koan. If this film has attained only a 40% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, it is because we, as a society, a people, a species, are not ready to comprehend it yet.

The outline of what follows is simple enough: Dalton cleans up the bar, there are fights, there’s an evil rich guy running the town, Swayze romances the local ladydoctor (Kelly Lynch), there’s a huge fight at the end, we find out Dalton killed a guy back in the day, everything’s resolved, Dalton stays around. I have given you the barest skeleton of the plot, but you must see it yourself to truly taste the rainbow, and to experience the movie’s protagonist. As the Coen Brothers once wrote, sometimes there’s a man. Yes; sometimes there’s a man.

This is where our understanding of Dalton must begin. Some believers in God, if they stop believing, are comforted by the notion that they have not actually lost God; the ideal being they believed in is still there, albeit inside them. It was in them the entire time. Such is Dalton.

If Dalton didn’t exist we’d have to invent him, because we need him. I’m not a man given to hyperbole — in fact, you might say I’m the person least given to hyperbole in the history of the entire universe— but Road House is, without a doubt, the single greatest thing the human race has done from the creation of the world up until the present moment, and I include vaccines and the idea of the talking horse in that list.

You may think this is a terrible eighties movie, but, oh, how blind you seem to me — this is a simple, simple retelling of Dante’s horrorpalooza through the multiple domains of the afterworld, if Our Poet in Florence had been on the less-groovy bottom basement of a black tar kick, and if instead of being led by Virgil, Dante himself had been armed with an unstoppable knee-kicking style. First, consider what Dalton is competing with in this film.

Let us now quote from the list compiled by Andrew Unterberger:

Full-cast bar brawls roughly every fifteen minutes

Lots of fat dudes with beards wearing suspenders

Monster trucks

Multiple repeatedly exploding buildings

“Pain don’t hurt”

Performances from all-time Top 20 That Guys Keith David and Kevin Tighe

Tons of ridiculously gratuitous nudity, including of Swayze himself

Performances from future Big Lebowski alums Sam Elliot and Ben Gazzara (in their respective good and evil roles)

A hysterically unerotic Swayze-Kelly Lynch sex scene set to Otis Redding’s “These Arms of Mine,” as if to say “Hey, remember that really successful movie I was in a couple years ago with all those cool classic soul songs?”

“A polar bear fell on me”

I get dizzy just listing all of these wonders, my soul is magnified by them, magnificat anima mea. And out of all of this, what do we remember?

Dalton.

Based Dalton.

Dalton, who lives eternally on TBS as a modern saint. Dalton could kill everyone in the movie from the first moment he appears — all of the characters with little effort — you, and I, reading at this very instant, and all persons and creatures living in the world at this moment, we are alive only because he chooses to let us live — we are so many spiders dangling over the fire to him — he could remove us from the world as a saint’s relics suck poison from wounds — but he does not kill us, does not allow us to die; it is an example of his endless decency and compassion for the human race that he allows us to keep breathing even today. We live solely by his dispensation, according to his wisdom.

What Swayze’s character amounts to is this: Dalton is the postmodern man. Masculinity, unfortunately, is all too often defined by its relationship with oppression. Manhood changed after the liberation of women, factory outsourcing, and the de-glamorization of war — men cannot define themselves by, respectively 1) dominating and not being women, 2) being the sole provider, and 3) fitting in authority systems with no moral compass. So what’s the right way to be a fella? Nobody’s sure. By the Reagan era, the notion of manhood is schizophrenic, with Rambo and Arnold and various ideas about what it is to be a Badass Dude floating around.

These notions of masculinity are unfortunately tied in with cynicism and nihilism: the tough guy who doesn’t think, doesn’t feel, and isn’t part of a larger society, who makes his eagerness for violence and general inarticulateness into virtues. None of this stuff would fly with the idea of manliness that obtained in certain warrior classes in the old country. Chaucer wrote about the knight in The Canterbury Tales:

“Though so illustrious, he was very wise

And bore himself as meekly as a maid.

He never yet had any vileness said,

In all his life, to whatsoever wight.

He was a truly perfect, gentle knight.”

By the time of Road House, the Berlin Wall is falling, the idea of John Wayne and his steak-filled colon is good and dead and Vietnam’s long over, and there’s no crawling back to the lugnut machismo of the early 20th century. Where do we go from here? Who will show us the way, combining our deep need for doing badass flips ‘n’ kicks ‘n’ tricks with our emotional and spiritual needs as humans and adults? Dalton. Dalton will. Dalton is where the sixties collide into the eighties, and the result, my friends, is a flavor festival unlike any we have ever tasted.

Dalton is the moment when manhood turns its back on Reagan and Rambo, where Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance meets Sam Peckinpah, and it is just absolutely bazonkers, like a soap opera that begins by teaching us Bible parables and ending with a donkey on the Supreme Court.

Dalton is such a superior being — philosopher, mystic, poet, hard demigod — that Sam freakin’ Elliot is his wingman. Sam Elliot, of Tombstone and everything else. Dalton is the place where all the confused intuitions we have about what a man is supposed to be — intense and easy-going, intelligent and instinctive, restrained and real, passionate and peaceful — meet and are resolved. These are all competing needs, and Dalton is where those needs meet. If modern masculinity is a Gordian knot, Dalton is the postmodern knife which cuts it away. “Companions, the creator seeks, not corpses, not herds and believers,” Nietzsche wrote. “Fellow creators, the creator seeks — those who inscribe new values on new tablets. Fellow creators, the creator seeks, and fellow harvesters; for everything about him is ripe for the harvest.” Is it a bad movie? I don’t know, is bacon a “bad” food? Have we earned the right to judge bacon? No? Then, ye doubters, by what right can you pass judgment on the Road House?

Again, I must stress, Dalton is a bouncer so amazing that in a pre-Internet age— remember, there are no message boards for this—he is already the most legendary cooler that has ever been. How do other people know this? As other reviewers have asked, is there a circular? A newsletter, passed around bouncers? Who writes it? How do they gather information? Is there a ranking? I don’t mean to dispute the ways of James Dalton; the man works in mysterious ways, his wonders to behold. It could be that the bouncers have a kind of gestalt hive-mind, which would explain much.

What is this man doing in Missourah, all in-movie explanations to the side? Surely he could get work in Canada or Valhalla, as could we all if everything fell through and collapsed into pure gonzo frolics. The only conclusion is, Dalton comes to the Double Deuce outside of Jasper much as Brooks Robinson was sent down from a higher league. Billy Joel sang “We Didn’t Start The Fire” and here is the Cooler who will put out that fire. Dalton is the bouncer the legends foretold; this is the Bouncer who will Bounce Up Man.

He is the postmodern hero: he is okay with feminism, symbolically represented by Dr. Elizabeth “Doc” Clay. He is a deep-revolving thinker. His code, of three rules, can be applied to any human situation, ever:

The sage said:

“All you have to do is follow three simple rules.

One, never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected.

Two, take it outside. Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary.

And three, be nice.”

![]()

Writers have called Road House surreal: MST3K‘s Michael J. Nelson calls it “the Fanny and Alexander of bad movies.” Roger Ebert said “Road House is the kind of movie that leaves reality so far behind that you have to accept it on its own terms.” Emily Stephens, who quoted both reviews, said “Watching Road House is a bit like watching Last Year at Marienbad or Synecdoche, N.Y.” But I disagree; our world is far more like Twin Peaks then it is CSI. I suggest Road House is much closer to reality than these writers want to admit. The Russians have known this for generations, which is why they drink and make beautiful culture.

Finally, as the writers Grant Morrison and Mark Waid pointed out long ago, Superman’s enemies can be seen as cracked-mirror reflections of the Man of Steel himself, aspects of his character taken to a villainous extreme: “Brainiac represents Superman’s alien nature without his human compassion. Luthor is the only man on Earth capable of being Superman’s equal but has squandered his unlimited potential on evil.” Bizarro is Superman’s earnest potential to do good but inverted to be dangerous.

If Dalton is the New Postmodern Man, then the bad guys in Road House are bad caricatures of the worst stereotypes of masculinity, beyond the moistest fungal corners of Reddit. The bad guy, Brad Wesley (Ben Gazzara) is the Dark Father, the idea of the male as a Poison King, lording it over the community with wealth and power, decorating his house with the carcasses of beasts he has slain, but can never truly claim. The entire whirling constellation of redneck goons and various others are shades of the manhood’s worst sins: brutal gluttony, shameless sloth, unthinking stupidity, petty wrath.

And then there’s Gazzara’s right-hand man, referred to only as “Jimmy,” played by Marshall Teague. Jimmy is the twisted shadow of Dalton; the bad idea of manhood that Dalton must de-trachea to purify the Road House and the town. It is Jimmy who tells us in the shirtless brawl which ends the film that he used to have sex with men like Dalton when he was in prison. Is Jimmy an insecure homophobe, a simple braggart, or just scared out of his wits and saying whatever comes to mind? Perhaps all three.

![]()

As Unterberger points out, Jimmy prefers to keep both the sexual preference and consensuality of his prison trysts ambiguous, which is nuts for a purportedly tough guy in a fight, but makes total sense for a dude who is a living symbol, the dark twin to Dalton, the negative wicked spirit of masculinity. A guy so stereotypically “manly” that he is a child’s idea of what masculinity is; a bro so shallowly, two-dimensionally “manly” that he has nothing to feminize him at all, and thus only has sex with pretty men such as Dalton, and Dalton kills him, banishing the fiendish dead ghost of toxic manhood forever.

At the end, we learn that nothing has happened without Dalton’s consent. Dalton, like the French Revolution, can never be put away. Dalton is what we might be: it’s his way or the highway, and one day, when money becomes irrelevant, the State dissolves, and Dalton ushers in the Golden Age, we will all regret that we messed with his car … and each other. Doc asks Dalton, “How’s a guy like you end up a bouncer?” And he replies, “Just lucky I guess.”

So were we, Dalton. So were we.