Two Difficult Tasks for My Fellow Black Writers: Bring “Lynching” Back, and Keep Writing

Politics Features

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.—William Faulkner

If you want to be a normal person and live a normal, happy life, don’t ever take a course called Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. Don’t read books by Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, or Toni Morrison, William Faulkner or James Joyce. Along with many other issues you’ll have, you’ll likely become one of those strange people obsessed with language and all its power. You’ll start to consider the way a word sounds, or feels. You’ll wonder at its origins, its social significance. Don’t ever study poetry either (not Harryette Mullen, not T.S. Eliot), because then it’ll only get worse. Choice of verbs, placement of commas, line breaks—you’ll start to believe that language is everything, that entire histories can be built upon a single word. You’ll start to think, like me, that the insistence on using one word over another could mean… change.

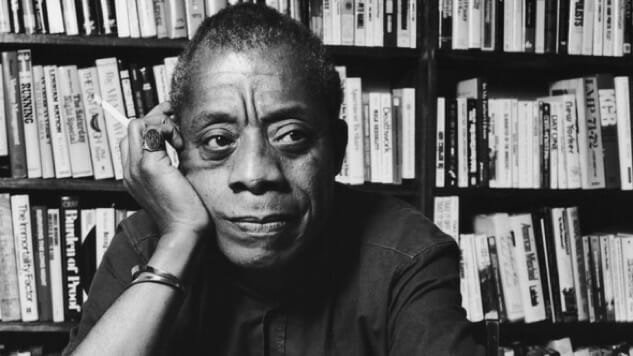

And then you’ll write a sentence like that, and obsess over whether or not “change” is the correct word. Because what is “change,” anyway? After Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were murdered—no, lynched, by police, I read an essay by James Baldwin that was published 50 years ago in 1966, A Report from Occupied Territory. Written before I was born, before our black President, before all this “progress,” we’ve experienced—so how could so much of an essay on the politics of commonplace police brutality ring true for today? How could it be that, save for a few differences in language (like Baldwin’s use of “Negroes”), much of the circumstances presented in the essay are precisely the same? Harlem is still an occupied territory; majority black neighborhoods are still over-policed to death and politicians are still pretending to be concerned with the state of affairs—still hand-wringing and wondering what in the world can be done—all while insisting that we must have faith in the law, and in this great land, whether they do us violence or not.

In addition to Baldwin, I also made the mistake, I think, of reading up on Ida B. Wells. Someone asked me, point blank, how to “fix” racism in America, how to stop police from killing black people. When I realized that I didn’t have the exact answer, I turned to one of my idols, one of my mother’s favorites. What, precisely, did Ida B. Wells do to stop lynching during her time? I practically Googled.

It was a mistake because I had to come to terms with the fact that my hero didn’t stop lynching in her time, and that she also believed she suffered many failures along the way. There was the case she won after getting kicked off of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad—a huge victory for the movement. But she lost it on appeal, and was incredibly distraught.

“I felt so disappointed because I had hoped such great things from my suit for my people… O God, is there no… justice in this land for us?”

How devastating, to seek “answers” in history, only to see how clearly American history repeats itself. Her words, phrased just a tad differently, could be a tweet from any number of black people expressing anguish online today. Of course, Wells would not be deterred and would go on to fight against and write about the horrors of lynching in America, among other injustices. One of her main goals was to demolish the myth of lynching as a response to some kind of criminal behavior perpetrated by blacks. Lynching, she discovered and exposed through her tireless research, was not a reaction to crime, but a violent means of controlling an entire group of people, through fear.

For that reason, I believe that lynching is a word that must be revived today, in 2016. Because people are being killed, and the lesson many blacks are taking away is that they should live in a state of fear; we have seen that there is no “behavior” that will not be deemed aggressive, criminal or violent in the face of so many police. There is no way to avoid being killed by police, as long as you are black.

“Lynching” is a word that makes me flinch and grimace; it makes me uncomfortable—more than nigger, more than Brock Turner, or practically any other word or phrase in the English language. But more importantly, it’s a word that sounds and feels out of date; not of this time or era. Grainy black and white photos come to mind, silent films, minstrel shows—things we have no use for anymore. Surely, my mind tells me when I see it, we cannot have any use for the word “lynching” in 2016.

Like most writers and artists, I’ve learned that if something makes me uncomfortable, there’s a good chance that it may be useful.

When a cop kills a black man, woman or child in America, one of the most infuriating things is the sanitization of the language used to report on the killing. Journalists, unaware or uninterested in how they perpetuate white supremacy, go out of their way to paint the portrait of a tragic, but ultimately unavoidable situation. And that’s usually just the best case scenario. More than likely, they work to criminalize the victims of the killing—be those victims men in legal possession of firearms, like Philando Castile, or children playing in parks, like Tamir Rice. “Officer-involved shooting” is a phrase that seeks to strip these lynchings of all racial motivation. It’s one of the things that makes it so easy for people to declare that police brutality has nothing to do with race, politics or class.

Lynching is simply, an extrajudicial execution. In a state where blacks were meant to be free, police would not be the jury, the judge, and the executioner—and yet they’ve been given such power by the state (for this reason—as in, because blacks in America were not meant to be free, many believe that police reform in America isn’t even possible). Lynching, back in the days of Ida B. Wells, was also associated with a mob. But just because our mobs in 2016 wear badges, and work at all levels of government—from States Attorneys, to prosecutors, to members of the Department of Justice—it doesn’t mean that lynching doesn’t exist. Lynching has merely evolved. We don’t need to see white robes and nooses at every killing by police to start calling it like it is.

“A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” are words that were printed on a flag that flew from a NAACP office building in 1936, long after people like Wells began to fight against the domestic terrorism white Americans inflicted on blacks. Yesterday at a protest in Union Square, someone held a sign that said the same thing. The flag has risen again, and been updated, in New York, because the violent past, for black Americans, isn’t even past.

The reason I felt that reading Baldwin and Wells this week was a mistake is because I had other things to do, other than be in a constant state of rage. Like so many of you, I have things I need to write—15 pages into the second draft of a TV pilot I’ve told a select few (and now, the whole of the internet) about, and I’m so close to finishing it and sending it to a few kind people I know—and boom. Two more black people are killed and I realize I haven’t solved racism, I haven’t changed a damn thing for my three boys and so why the hell am I writing a TV show, or anything else for that matter? This is not a common feeling for me. I’m not one of those writers who exists in a near-constant state of self-loathing, or always wonders if I’m good enough (even though the world seems to insist that this is how real writers are supposed to feel, most of the time). I’ve spent the last few months of my life listening to little else other than Lemonade and ANTI—my confidence level is at a terrifying, all-time high. I even started running, like one of those annoying people concerned with her health, because she has things to write and wants to be around for a long time to write them.

But the way white supremacy’s bank account is set up, I didn’t want to write anything creative this week. If I couldn’t come up with a solution to this problem I didn’t create, I felt like I had no business writing at all. And that’s how the domestic terrorists—the police who kill, and the high-powered mobs that support them—win. Because if I felt it, I know that my fellow writers and activists did too, and I know that so many of us didn’t write this week, which is another way of saying we didn’t work, we didn’t live and we weren’t free (“I’ll tell you what freedom is to me—no fear”—Nina Simone).

Today, people will tell you that Black Lives Matter activists must apologize for, or explain the Dallas shooting. They will tell you to forget Philando, Alton, and the countless others lynched by police officers for a moment—officers who will go on paid leave, rarely be charged for the crimes, and likely never serve time. We activists and writers will be asked to spread the message of non-violence that warms the hearts of white people all across America, and many of us will attempt to distance ourselves as far away as possible from those who carried out the most recent violent act that’s making headlines.

I’m not going to do any of that, in part because a great writer once told me “people committed to liberating black, queer, and trans people have nothing to explain, apologize for, or disassociate from.” Additionally, I see the energy I would spend trying to convince others that cops being killed in Dallas does nothing to alleviate my rage, nor is it comparable to the constant violence black Americans are witnessing at the hands of police who go unpunished (and the state, which includes prison systems and broken educational systems), as better served elsewhere. And I believe those writers and other creatives concerned about black lives also have precious energy they’d do better to conserve. I know there is and has never been a war on cops and I know that the members of law enforcement in this country are not the members of an oppressed group of people, demanding that their voices be heard.

Men were lynched this week. And black writers who should have written things—things that have nothing to do with lynchings or blackness, or politics, or things that have everything to do with them—didn’t write. Some of us wrote, but begrudgingly so. We are not going to stop the lynchings right now, but as we keep working towards a change that isn’t mythical and a progress that is visible everywhere, one of the greatest acts of rebellion we can commit to (and readers of Baldwin, Hurston, Walker, Morrison and so many others know this all too well) is the act of unapologetic, uninhibited creation. Black writers, we must call things as they are, and we must write. As someone once said—do it for the culture.

Shannon M. Houston is a Staff Writer and the TV Editor for Paste. This New York-based writer probably has more babies than you, but that’s okay; you can still be friends. She welcomes almost all follows on Twitter.