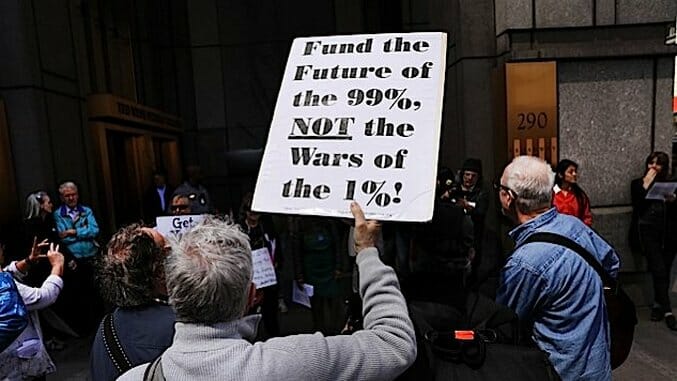

A Resistance That Is Not Explicitly Anti-War Is Doomed to Fail

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Politics Features War

In February 2003, citizens from hundreds of cities around the world participated in a mass protest against the impending military occupation of Iraq. Conservative estimates suggest that between six and ten million people worldwide took part, while others put the actual number closer to 30 million. Specific figures aside, it was—and remains—the largest coordinated protest in human history. Of course, the millions of activists that participated were, in the end, unable to stop the invasion of Iraq, but the 16 subsequent years have proven that each and every one of them was absolutely right to oppose the war. Iraq in 2017 remains an unstable, dangerous warzone, prone to regular horrifying attacks of sectarian violence.

The country has also become fertile ground for the incubation of newer, crueler enemies, who have taken advantage of the power vacuum to establish a foothold from which they have relentlessly terrorized peaceful citizens in both the Middle East and the western world. So, knowing what we know about the disastrous invasion of Iraq, it should be a given that if the United States government continues along its current path toward military confrontation with North Korea, Iran, or—in an almost-unthinkable worst-case scenario—both, it would surely mean a humanitarian disaster the likes of which we have not encountered in decades. Perhaps not in our lifetimes. And the closer America gets to this disastrous possible future, the more necessary it is that leaders once again be met with unprecedented, widespread, international—yes—Resistance.

Since the election and inauguration of Donald Trump, there have been numerous inspiring marches and protests in defense of everything from women’s and immigrant rights to reproductive and environmental justice. For the most part they’ve been extremely worthy causes (and in the case of the airport protests during Trump’s Muslim ban weekend of insanity, vitally necessary). But we haven’t seen much in the way of antiwar activism. Part of the reason may be that Trump has simply had less time to wreak havoc on the international stage—although he’s faced fairly widespread criticism for the botched Yemeni raid that claimed the lives of a United States SEAL as well as dozens of civilians, including an eight-year-old girl, his use of the MOAB in Afghanistan, and the generally alarming uptick in collateral damage casualties across the board. But even now, as the possibility of large-scale military conflict is beginning to feel like more and more of a reality, there’s been plenty of condemnation and hand-wringing, but still not much in the way of direct action.

One possible reason for this is that by and large, Democrats, their surrogates in the media, and American liberals—who were often important allies in the opposition to Iraq—overwhelmingly supported Barack Obama’s gentler, smarter imperialism, which put fewer actual U.S. troops at risk but still killed thousands of innocent civilians, destroyed several countries in the Middle East, and led to much of the same violent, lawless fallout as Bush’s whisky-crazed cowboy foreign policy. It’s rhetorically difficult to effectively oppose something when it’s clear your objection is based more on semantics than an actual moral opposition to what’s being done.

For example, liberals were mostly quiet about 8-year-old Nawar Anwar al-Awlaki’s death in the botched Yemen raid; perhaps that’s because when her 16-year-old brother, also an American citizen, was killed in a drone strike ordered by President Obama, these same people largely supported it. So, while it’s easy to see why liberals might be reluctant to make opposition to war or imperialism a major plank of the Resistance, this is something that’s going to need to change if the Trump administration makes a move to turn its current blustering playground bully rhetoric into something more substantial.

And to say there’s been a lot of loose talk with regards to North Korea and Iran lately would be putting it mildly. Although Trump’s apocalyptic comments were mostly walked back by aides and supporters, it’s really not that out of step with what the rest of his cabinet has been saying. Nor were his words far removed from recent comments by “moderate” Republican and beloved Resistance figure Lindsey Graham. Or, for that matter, President Obama. Regarding Iran, Michael Flynn seemed to suggest very early on in the administration that the country was going to be targeted in the near future, until any plans he may have had, along with the rest of his career, was abruptly cancelled due to his undisclosed contacts with Russian ambassadors and financial ties to the Turkish government.

Flynn’s failure aside, Trump’s Iran stance has once again becoming increasingly antagonistic. The Iran deal requires recertification every 90 days, but the President is apparently planning on finding them in violation of the agreement’s term—regardless of whether that’s a reflection of actual reality. Ironically, Iran is now insisting that the latest sanctions bill targeting North Korea as well as Russia is itself a violation of the deal, and they may have a point. In any case, it’s still unclear whether Trump’s rhetoric regarding both North Korea and Iran constitutes an empty threat, or if he does genuinely intend to seek war with one or both. But given his historically low approval ratings, and the fact that the only times the fairly hostile U.S. media apparatus has fawned over him—those moments when he Becomes the President—are when he’s launched bombs, it’s not unreasonable to take his blustering at face value.

Another reason to take the threat of unilateral military action more seriously than ever is that just a few weeks ago, when the Mooch jokes were flying, something disturbing slipped under the radar. While Trump’s move to appoint General John Kelly as Chief of Staff was met with mostly positive reviews based on the “stabilizing effect” it was hoped to have on the erratic and unpredictable President, we’re now faced with a situation where Kelly, along with Defense Secretary General Jim Mattis and Homeland Security Secretary General H.R. McMaster, have accrued virtually unprecedented power to control White House policy. Combined with the reality that Trump has already essentially surrendered decision-making power with respect to the Middle East/north African war theater to military strategists, you don’t need to be a conspiracy-minded paranoiac to be concerned with what this new-look White House might mean for American foreign policy moving forward.

All of this is to say that in order for these potentially cataclysmic outcomes to be avoided, liberals in America are going to need to reverse the flirtation they’ve been having with hawkishness over the past decade (or arguably, the inclination towards hawkishness that they’ve always had, except from the years 2003-2008). They must move past the idea that a responsible, reasonable Democratic steward of American military empire is a viable solution to the problem of international instability.

Indeed, there’s been plenty of But-Her-Emails jokes in the wake of Trump’s recent North Korean threats, but Clinton was certainly no stranger to hawkish foreign policy, and had also participated in a fair amount of blustering towards both North Korea and Iran. One of her main foreign policy criticisms of Trump in the runup to the election was that he was too friendly with North Korea. And it’s also unclear whether, when it came to Iran, she wouldn’t have acquiesced to a more AIPAC-friendly foreign policy versus Obama’s ever-so-slightly antagonistic Israel stance (the Israeli lobbying arm, who hosted Clinton for a speech during the 2016 campaign, had invested millions of dollars into stopping the Iran deal before it gained traction). Though she did ultimately endorse the deal, it’s difficult to suss out whether this was due to an actual ideological commitment to a nonviolent resolution with Tehran, or if it was simply a matter of political expediency (of course, this question is typical of many Clintonian political stances). All things considered, while there’s absolutely reason to believe her foreign policy would have been more stable and nuanced than whatever it is that Trump’s doing, there’s no reason at all to believe it wouldn’t have ended up at a similar result.

In any case, while speculating about how Clinton’s theoretical administration would have been responding to the current international mise en scène can be instructive, it’s not immediately relevant to the threats peace-loving citizens across the world currently face. And while the Trump Administration’s moves toward military conflict must be vigorously opposed—ideally to the same or greater extent as Bush’s Iraq invasion was—it’s important that this opposition calcifies into something more permanent. For even if the best-case scenario for the current Resistance comes true—even if Donald Trump’s entire family is escorted from the White House in leg shackles—the end result will be a more stable, politically savvy Republican ascending to the Oval Office while high-ranking, unelected military officers occupy some of the most vital civilian positions in the White House. The threat for more war and conflict will not be washed away, and neither should the resistance to it.

That means that if Democrats do manage to reclaim power in 2018 and 2020, it must not be yet again under the promise of a smarter, more surgical version of the cruel imperialism that America has been perpetrating under presidents of both parties for decades. Just as single-payer healthcare is quickly becoming a litmus test among ascendant progressive Democrats, so too should dismantling the vast military-industrial complex that has wreaked havoc on the international stage for generations and drained America’s coffers beyond the ability to support a decent standard of living for its citizens. Indeed, if the Resistance is not vigorously opposing war with tangible, widespread, direct action in both the short term and the long term, it is superficial, tepid, and ultimately doomed to fail.