Disney’s Lost Rides: Fire Mountain, the Innovative Roller Coaster That Never Was

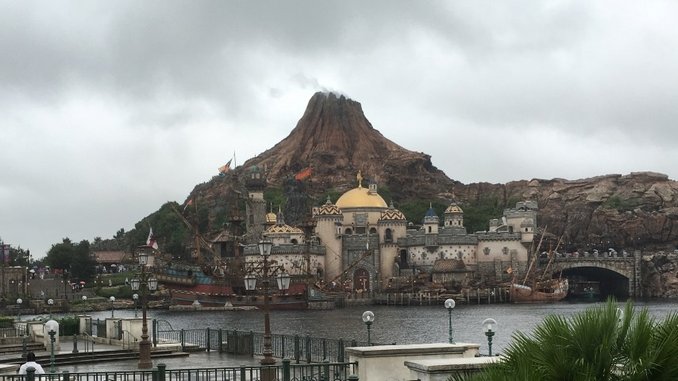

Header photo: Tokyo DisneySea--what Fire Mountain could've looked like. Photo by Garrett Martin. Travel Features Disney

Over the past six decades, Disney’s Imagineers have designed many theme park rides that were never actually built. Some were far along in development before the plug was pulled, while others were just ideas and concepts that never made it past the drawing board. We’ll be taking a look at these lost rides of Disney, from the exciting to the mundane, over the next few months. This week, we look at an innovative roller coaster that changed thoroughly throughout its development, before being quietly cancelled early this century.

In the world of Disney theme parks, you know a ride is going to be special if it has the word “mountain” in its name. Ever since Disneyland’s Matterhorn first opened in 1959, mountains have loomed large over Disney parks, standing as the biggest and most thrilling of E-ticket attractions. Guests first rode the cosmic roller coaster Space Mountain in the ‘70s, Big Thunder Mountain Railroad injected some wild wilderness thrills into Frontierland a few years later, and by 1992 Splash Mountain was sending its riders down a 50 foot drop at both Disneyland and Disney World. 21st century creations like Expedition Everest, Avatar Flight of Passage, and Tokyo DisneySea’s Journey to the Center of the Earth might skip the word “mountain,” but they still keep the implicit promise made by their design: if you see a mountain in a Disney park, you know there’s an amazing ride inside.

The early ‘00s almost brought another mountain to the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World. The site of a then-recently shuttered opening day ride would’ve been the home to a thrilling new attraction that broke new ground for a roller coaster. Over the course of its development its proposed footprint moved from Fantasyland to Adventureland, and its connection to a classic live-action Disney film would be dropped in favor of a tie-in to a then-upcoming animated feature. And then, when that movie flopped, and when real life events left an indelible impact upon the world at large, the whole project would be dropped—only for some of its ideas to be reused at another Disney park on the opposite side of the planet.

This is the story of Fire Mountain, one of two new mountains that almost came to the Magic Kingdom at the beginning of this century. And it starts, quizzically, with a completely unrelated film from 50 years earlier.

![]()

Walt Disney had toyed with live action as far back as his “Alice Comedies” of the ‘20s, in which a real actress appeared on-screen alongside animated characters and backgrounds. He revisited that combination of live action and animation in the 1940s, during a stretch of time when poor box office results, an ugly labor dispute that was poorly handled by Disney, and the effects of World War II drove the company away from full-length animated features and inspired a series of “package” films made up of various individual segments bundled together. A handful of Disney films of the mid ‘40s combined animation and live action, including the infamous Song of the South, and the True-life Adventures series of nature documentaries launched in 1948. By 1950 Disney was ready not just to return to feature-length animation, but to finally pursue full-length live action movies, as well; that year Walt Disney Productions released Cinderella, their first non-anthology animated feature in eight years, in February, and followed it up four months later with a live-action adaptation of Treasure Island.

Treasure Island was a critical and commercial hit. Disney followed it up with a string of adventure films shot in England: 1952’s The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, 1953’s The Sword and the Rose (about Mary Tudor and Henry VIII), and 1954’s Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue. Robin Hood was a success, but the other two fizzled, with the latter slumping at the box office right as Disney started production on its most ambitious live action film yet. With major stars like Kirk Douglas and James Mason on board, shooting scheduled on location in Jamaica and the Bahamas, and an arduous production marred by poor weather and technical problems, Disney had a lot of money invested in 1954’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. If it sunk at the box office it could have pulled the whole company down with it.

Well, it didn’t sink. 20,000 Leagues debuted to fantastic reviews and big box office at the end of ‘54, and became one of Disney’s most beloved live action films. It was so popular that it’s been a mainstay in the Disney parks for decades; Disneyland had a walkthrough attraction based on it in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Disneyland Paris has a similar walkthrough that can still be found today in its Jules Verne-inspired Discoveryland area, and Tokyo DisneySea has a ride named after the film in a different Verne-themed mini area. Most notably of all, at least for Disney fans of a certain age, was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: Submarine Voyage, a ride that opened alongside the Magic Kingdom in 1971 and thrilled guests for over two decades before quietly closing down in 1994.

Like the Submarine Voyage at Disneyland, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was a submarine ride that didn’t actually go under the water. Set in a lagoon in Fantasyland, the ride used a variety of Imagineering tricks to make it seem like it took guests deep into the ocean, while it simply glided at surface level through a show building obscured by rockwork and waterfalls. Despite remaining a popular ride for over 20 years, it was closed in 1994, probably because it was expensive to maintain and had a low hourly guest capacity. The lagoon was renamed Ariel’s Grotto and used as a Little Mermaid-themed photo spot thereafter, but the plan was always to replace it with something new—something big and exciting.

![]()

As the ‘90s were approaching their close, the Magic Kingdom had a prime piece of real estate at the heart of the park that was essentially going unused. And with the park’s 30th anniversary approaching in 2001, Disney CEO Michael Eisner had big plans for the Magic Kingdom, including two new E-ticket attractions that would open within a few years of each other and out-thrill even Space Mountain and Big Thunder Mountain. Both would also have the word “mountain” in their name, letting customers know they were a big deal, and one would preserve the Jules Verne connection lost when 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was closed.

The first planned ride would have starred a collection of villains from Disney’s animated features, and be themed to the Bald Mountain segment of Fantasia. We’ll talk about that unbuilt ride at a later date. The other ride, tentatively planned to open by 2001, was to be called Fire Mountain, and would’ve been set within Vulcania, the volcano from the 20,000 Leagues film that serves as Captain Nemo’s secret headquarters.

Initially Fire Mountain would be built where the 20,000 Leagues lagoon had been located since the Magic Kingdom opened in 1971. It would recreate the volcano from the film, and within it would be a ride that started off as a fairly traditional roller coaster. As the train throttled through the volcano, though, it would become clear that an eruption was about to happen—at which point the ride system would switch to an inverted roller coaster track. That’s the kind of roller coaster where the track is above the car, so it feels as if you’re flying or dangling instead of riding a train. The eruption within Vulcania would cause the switch within the ride’s storyline—essentially you’d be rocketing out of the volcano, with the suddenly inverted coaster making it feel like you were now soaring through the air.

This original version of Fire Mountain would accomplish a handful of goals for Disney’s Imagineers. It would keep a Jules Verne-related ride in the park, and one that still had a connection to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. It would be significantly more advanced than the other roller coasters in the Magic Kingdom, combining two ride systems in a way that had never been done before. And, per Eisner’s expectations, it would add another main event attraction to the park’s lineup—while replacing one that had been shut down.

Of course, as you should probably expect by this point, none of this happened.

The history of Fire Mountain is more convoluted than that, though. The original idea of building it on the 20,000 Leagues lagoon was scrapped, with the Bald Mountain proposal being slotted in for that land. Eisner still liked the Fire Mountain project, though, and a new plan was hatched to build it in Adventureland. This new location had no connection to Jules Verne, and really, as pivotal as the 19th century writer was to literature and Disney’s film history, it wasn’t exactly the kind of tie-in that the synergy-loving Disney brand was known for in the ‘90s. Fortunately the company had the perfect concept for this new ride in a film that was in production and scheduled to open in 2001. As 1999 unrolled, and Eisner solidified plans to build both rides, Fire Mountain would no longer be loosely themed to one of the locations from 1954’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea film. It would now be based on an upcoming animated adventure from the directors behind Beauty and the Beast. Instead of a volcano lost somewhere in the Pacific, Fire Mountain would take guests on a journey to Atlantis.

![]()

By the late ‘90s, the Disney Renaissance formula was running dry. The animated blockbusters of the early part of the decade had given way to films that performed respectably at the time, and are still fondly remembered today, but didn’t match up to the success of Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid or The Lion King. When Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, two veteran animators who had directed Beauty and the Beast and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, were thinking up new projects in 1996, they knew they wanted to try something different.

Inspired by the works of Jules Verne and the kinds of stories that would fit in the Adventureland area of Disney’s theme parks, Trousdale and Wise struck on the idea of a movie that explored the mythical lost city of Atlantis. It wouldn’t be about royalty, and it wouldn’t have talking animal sidekicks—it would be an action-adventure in the mold of the Indiana Jones movies, set at the start of World War I, and influenced by science-fiction and the architecture of different cultures from around the world.

Disney signed off on the movie, but had to realize that it was a risk. Trousdale and Wise avoided so much of what Disney’s movies of that era were known for. Disney’s run of animated hits that decade were all musicals; Atlantis wouldn’t have any songs. Instead of a fairy tale or a classic piece of literature, it would be based on an original story, although one influenced by Jules Verne. Instead of Disney’s familiar art style, characters would be based on the art of comic book artist Mike Mignola, the Hellboy creator who served as a production designer on the film. Atlantis was created in an era when Disney was trying to find a new direction forward after the Disney Renaissance had run its course, and there was no guarantee it would register with audiences the same way recent movies like Tarzan and Mulan had.

Still, Disney was all in on Atlantis. The movie’s release would be supported by multiple marketing tie-ins, videogames, and a toy line. An animated TV spin-off was planned. And with a major new roller coaster already greenlit for Adventureland—one similarly inspired by Jules Verne—it only made sense for Atlantis to also get its own theme park ride. Fire Mountain said goodbye to the last vestiges of its 20,000 Leagues connection, and hello to Trousdale and Wise’s vision of Atlantis.

To get to this version of Fire Mountain, you’d walk through a new passageway that would be built in Adventureland between Pirates of the Caribbean and the Jungle Cruise. The queue would’ve been themed as a camp set up by the movie’s Whitmore Enterprises, which was now giving tours of the world famous sunken city of Atlantis. The ride would still be a roller coaster that switched tracks halfway through, and it’d follow a somewhat familiar theme park story: in the middle of what should’ve been a safe trip, everything goes wrong when the volcano suddenly erupts. The mountain itself would belch smoke and flame throughout the day, and serve as a new icon for Adventureland. The volcano wouldn’t have been visible elsewhere in the park, but guests staying at the Polynesian Village Resort would’ve seen it looming on the horizon—a scenic view that would’ve perfectly fit that hotel’s theme. With construction initially planned to start in 2000, the ride was projected to open in October, 2001—just in time for the Magic Kingdom’s 30th anniversary celebration, and only a few months after Atlantis was in theaters.

And then, like Atlantis itself, these plans just disappeared.

![]()

Fire Mountain was never built in the Magic Kingdom, or in any other Disney theme park. This era of Disney parks history is littered with grandiose plans that never came to fruition, or that were scaled back so thoroughly that they barely resemble the original goals, and both Fire Mountain and Bald Mountain are on that list. There are a few obvious reasons we can point to for its quiet cancellation, but there’s still as much mystery surrounding the end of Fire Mountain as there is the legend of Atlantis.

The most obvious reason for the project’s demise is that Atlantis simply wasn’t very popular. When it was released into theaters in 2001, it was part of a run of flops that imperiled the very survival of Walt Disney Feature Animation. All franchise plans were quickly put on hold, with the only follow-up being a direct-to-video sequel repurposed from three episodes of the proposed TV show.

Of course, it’s believed that Fire Mountain was supposed to open in 2001. Based on that timeline, it should’ve been deep into construction before Atlantis ever hit theaters. No work was done, though. Even if Atlantis had been the second coming of The Lion King, Fire Mountain couldn’t have opened in 2001, or even in 2002. So clearly the plans had stalled out before the movie was released.

Another theory is that the wave of expansion that Fire Mountain would kick off in the Magic Kingdom was in part a reaction to Universal’s second Orlando theme park, Islands of Adventure, which opened in 1999. Eisner would counter Universal’s attempt to become a true resort destination that rivaled Disney by building these major new E-tickets. Islands of Adventure opened weakly, though, and quickly proved to be less of a threat than Eisner feared. Without that pressure, there was now less of a need to rush major new projects, thus pushing Fire Mountain back or cancelling it altogether.

There’s also ample proof that Eisner, who spent exorbitantly on Disney’s theme parks during the first decade of his tenure, had drastically tightened the pursestrings by the late ‘90s. Other Disney parks projects started at the end of the ‘90s, including entire theme parks like Disney California Adventure in Anaheim and Walt Disney Studios Park in Paris, were given wildly insufficient budgets, resulting in lackluster parks that guests roundly rejected. It’s entirely possible that Fire Mountain was simply a victim of the budget cuts that spread through the parks division as the 21st century beckoned.

If the plan was to simply delay Fire Mountain, and build it at some point after that 2001 target date, something outside of Disney’s control would have put an end to that. The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, drove America deeper into an already existing recession, and had a chilling effect on travel and Disney parks in particular. Attendance dropped significantly after 9/11, and as a result many projects were cancelled. If there were still any plans to build Fire Mountain after Atlantis’s weak performance, this tourism industry slump would’ve put an end to them.

![]()

For whatever reasons, Fire Mountain was never built. The plot of land next to Adventureland that would’ve held the Atlantis version of the ride is still undeveloped. The lagoon that once housed the 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ride was drained in 2004, and eventually became the site for the New Fantasyland expansion and the Seven Dwarfs Mine Train roller coaster. Today Fire Mountain exists solely through Disney message boards and articles like these, where passionate fans try to divine the true story from what little scraps of information have been uncovered.

Fire Mountain was never built, neither in the Magic Kingdom or anywhere else, but you can still get an idea of what it could’ve looked like if you visit Tokyo DisneySea. The centerpiece of that gorgeous park is a large volcano inside which sits the Mysterious Island area. There are two rides within the caldera of this Jules Verne-themed land, including a version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea that has an entirely different ride system than the long-gone Magic Kingdom version, but follows a similar storyline. The other ride, Journey to the Center of the Earth, is an Imagineering masterpiece. It’s not a roller coaster, but its story might sound familiar: you’re on a trek deep into the earth when suddenly disaster strikes. The volcano you’re traveling through erupts, and your vehicle suddenly lurches forward at high speed and rockets out the side of the mountain. When you’re done, you can go eat lunch at the only sitdown restaurant in the caldera, a beautiful little restaurant carved into the side of the volcano and called Vulcania. If you’re there at the right time, you’ll hear the volcano erupt above you, its billows of flame and smoke licking the sky. It’s not Fire Mountain, but it’s still amazing—and the closest you’ll get to ever seeing that never-built Disney attraction.

Various sources contributed to the information in this article, including:

WDW News Today

20kride.com

Yesterworld

Senior editor Garrett Martin writes about videogames, comedy, travel, theme parks, wrestling, and anything else that gets in his way. He’s on Twitter @grmartin.