Sailor Moon and the Complicated History of Queer Gender Expression in Anime for Girls

TV Features Anime

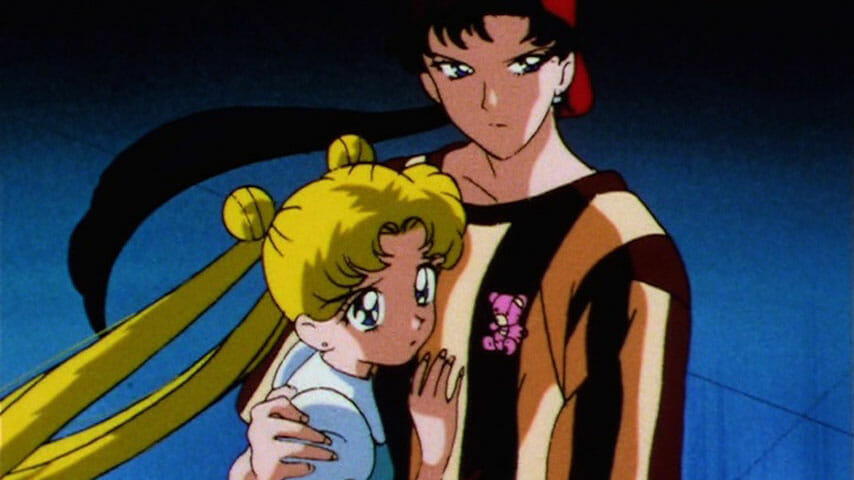

The first queer couple I encountered in anime was censored. Most kids who grew up in the ‘90s are aware that in its original form, Sailor Moon’s Sailor Neptune and Sailor Uranus aren’t actually cousins, but were instead a lesbian couple. The homophobic revision of these characters is so blatant it makes rewatches of the dub absolutely comical. This wasn’t the only revision the Sailor Moon dub made to the source material for the sake of censorship. Zoisite, an early villain who is an effeminate gay man in love with fellow villain Kunzite, is changed to a female character. Given Uranus’ butch persona, they may have wanted to do the same with her. Uranus is rarely if ever depicted in feminine clothing save for when she’s in her Sailor Scout form, rendering the possibility of portraying Neptune and Uranus as a straight couple nigh impossible.

Sailor Moon’s censorship doesn’t end there either. Perhaps the most ridiculous example comes from the Italian dub. In the show’s final season, Sailor Stars, we’re introduced to the Sailor Starlights, a group of three Sailor Scouts who disguise themselves as a boy band in order to find their lost ruler, Princess Kakyuu. The season is meant to play up how large the Sailor Moon universe is—the Sailor Starlights are from a distant planet in a far-off star system, and the powers they possess are unlike anything the main cast of Sailor Scouts can do. In particular, the Sailor Starlights are able to physically alter their bodies into male forms. When they transform into Sailor Scouts, their physicality alters back to their original selves. It’s easy to read the Sailor Starlights as genderfluid characters, given their distance from Western ideas of gender presentation as well as their unique ability.

The Italians weren’t having it. In the dub, when the Sailor Starlights transform, they are physically replaced with their twin sisters, who supposedly are just waiting in some astral, in-between phase to be summoned. Their voices change from baritone male voice actors to lilting female voices, as if to emphasize the difference between the civilian brothers and Sailor Scout sisters. As you might imagine, it’s completely ridiculous and only draws attention to the inherent queerness hiding in the series.

The blatant queerphobia of these dubs sometimes distracts from the other, more subtle problems present in portrayals of gender-nonconforming and trans characters in shoujo (aimed at young girls) anime. Zoisite is portrayed as jealous and insane when Kunzite off-handedly compliments a woman. In SuperS, we’re introduced to a gay villain named Fisheye who wears feminine clothing. Animation has a long history of queer villains, but Fisheye in particular acts in a predatory way towards Tuxedo Mask on multiple occasions. This coupled with the ease in which we can read Fisheye as a trans woman implicates transness as being duplicitous and dishonest. Despite Sailor Moon’s relatively good representation for its time period, it also deploys queerphobic tropes to develop a lot of its supporting cast.

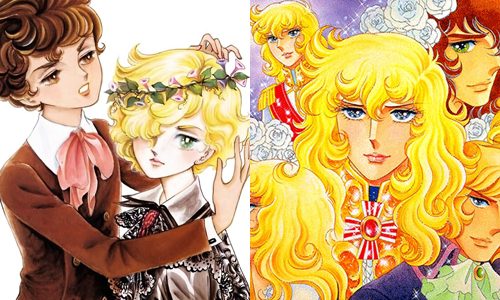

That said, most queer characters you’ll find in anime will most likely be from these shoujo anime, particularly ones that are adapted from manga written by women. Much of this has to do with the way censorship laws worked in Japan in the ‘60s and ‘70s. According to Boys Love Manga and Beyond, a cohort of female manga artists known as the Year 24 Group revolutionized the space of manga and formed early notions of what would become a shoujo canon. Mangaka like Keiko Takemiya pioneered the Boys’ Love genre with her popular series Kaze to Ki no Uta, while Riyoko Ikeda published her proto-Girls’ Love series Rose of Versailles. Within their bibliographies, we can see many motifs that are present in shoujo anime today: a fascination with high society France, an excess of flower petals, sparkly doe eyes which cry thick, milky tears and a lighter, more blurred art style. Many panels have non-existent backgrounds, with characters floating in a sort of dreamlike haze of shading. Bodies are warped and exaggerated to the point of being nearly inhuman, with later artists like CLAMP elongating legs and thinning bodies in hyperbolic ways.

This softness lends characters in shoujo manga a natural androgyny, in which they can slip easily between genders while maintaining a neutral base. It lies in direct contrast to shounen manga (aimed at young boys) in which sharp and rigidly drawn characters have firm gender identities. Quickly after the meteoric popularity of Year 24 Group’s work, amateur mangaka began laying the groundwork for the doujinshi (self-published or fanworks) at the newly formed Comic Market fair. Many of these works were of a homoerotic nature and featured characters from known franchises or even real life Japanese celebrities like idols. The main audience for Boys’ Love manga were self-identified straight women who felt that they were able to express their gender and sexuality untethered from conservative and patriarchal ideas within the world of doujinshi. Scholars have identified that, despite most characters within Boys’ Love series being male, many occupy a certain “third gender” where they are genderless agents or are able to represent a range of gendered performance. These series also allow readers to engage with romantic stories not written by men who attach gender binarism or female stereotypes to the characters.

In recent years, the communities both in Japan and overseas for Boys’ Love (as well as Girls’ Love) have become increasingly diverse. Many cite Boys’ Love series as key elements in their path to queer realization, with many members of its audience being queer women and nonbinary people. In a survey conducted by the University of Psychology in Budapest, “provid[ing]… a guide to better understand my sexual dilemmas” was identified as a strong primary motive for the consumption of Boys’ Love. Less than half the participants identified as straight. Much of the derision aimed at Boys’ Love and similar genres depicting queer romances written by women may come from misogyny, given history’s tendency to undervalue works written by and for women.

Unfortunately, shoujo has always struggled to portray trans women effectively. Though trans women appear in shoujo perhaps more than any other type of anime, they are often relegated to villains, like in Sailor Moon, or are problematic in quiet ways. In Paradise Kiss, an anime based on Ai Yazawa’s manga that takes place within Tokyo’s high fashion scene, blatant queerness is present even within the show’s main cast. George, the main love interest, is a bisexual fashion designer who is never questioned for his sexuality. Within his circle is Isabella, a hyperfeminine trans woman whose calm demeanor is coupled with glamorous purple hair and avant garde outfits.

Isabella is a mostly positive representation of a trans woman, given she’s kind and a central cast member, but she is often relegated to a motherly role when the rest of the cast is allowed more time to grow dynamically. She’s mostly around to coach Yukari, the protagonist, in her budding romance with George. The only glimmer of conflict we get from Isabella comes from her unrequited crush on George. Isabella is content not to be with him, but simultaneously centers her identity around George, who often takes advantage of her affection. Isabella portrays a trans woman as naturally passive and an inactive agent when it comes to romance—she’s one of the only characters in the series without a romantic plotline. Isabella was written with love, but reinforces transmisogynistic stereotypes about women as best friends or guides for cis women.

One of the better and more complex trans women from shoujo anime comes from Lovely Complex, a show about an abnormally tall girl, Risa, and an abnormally short boy, Atsushi, falling in love. One of the supporting characters is a trans girl named Seiko who is in love with Atsushi. Seiko is mired in a lot of transmisogynistic tropes too, such as her plotline centering around a man’s love or the clumsy way she is outed, but Seiko is allowed to act as an active character in her rivalry with Risa for Atsushi’s affection. I’m not saying her portrayal is great, but after Seiko fails to win Atsushi over, however, she is accepted among her friend group and her pronouns are always respected. She’s a rare example of a trans woman being a part of a show’s cast who is not a villain or portrayed as insane, but rather, is allowed to grow and develop.

Lovely Complex also handles trans issues that we don’t often see portrayed in anime quite elegantly. During the course of the manga, Seiko’s voice deepens as a result of puberty, sending her into a panic. She rapidly detransitions and comes to school dressed in a hoodie and shorts, in direct contrast of her usual girly style. With encouragement from Risa, Seiko comes back to school the next day in her usual look and continues her voice training. It’s a rare moment where a character’s transness becomes a central conflict, but isn’t played for trauma or pity. Instead, Seiko is allowed to maturely handle a problem many teen trans girls face in their adolescence with maturity.

Queerness in shoujo are constantly changing, especially as lines between demographics are increasingly blurred. Many shoujo shows of today, like Diabolik Lovers or Akatsuki no Yona, have styles or plotlines we might more commonly expect from shounen. As such, an increasing number of shows are referential to or toy with genre conventions of these shounen anime. My Next Life as a Villainess pulls this off excellently by centering the typically male-targeted and misogynistic isekai genre, in which a character accidentally ends up in a parallel world like within a videogame, by having its female protagonist become the villain of a dating sim. Soon, she starts winning the affections of men and women alike. It’s a great show, and probably the best example of bisexuality in recent anime.

While Naoko Takeuchi had noble intentions when she set out to write Sailor Moon as a feminist series, she failed to account for the gender-nonconforming people who would grow up feeling alienated by the series’ occasional inflexible sense of gender. In an interview at San Diego Comic Con in 1998, she expressed that “Sailor Scouts are only girls.” In the same interview, she also stated Neptune and Uranus date because Neptune is “girlish” and “feminine” while Uranus is “boyish” and “has the heart of a guy”—why assign a gendered dynamic like this when their relationship needs no explaining? If shoujo wants to challenge patriarchal standards in anime and manga, it has to contend with its own implicit queer anxieties too.

Animation is uniquely suited for exploring queer identities. If you’re curious how, see how Serial Experiments Lain did it through Y2K information technology.

Austin Jones is a writer with eclectic media interests. You can chat with him about horror games, electronic music, Joanna Newsom and ‘80s-‘90s anime on Twitter @belfryfire

For all the latest TV news, reviews, lists and features, follow @Paste_TV.