Why Black Mirror: “Bandersnatch” Amounts to No More Than a Gimmick

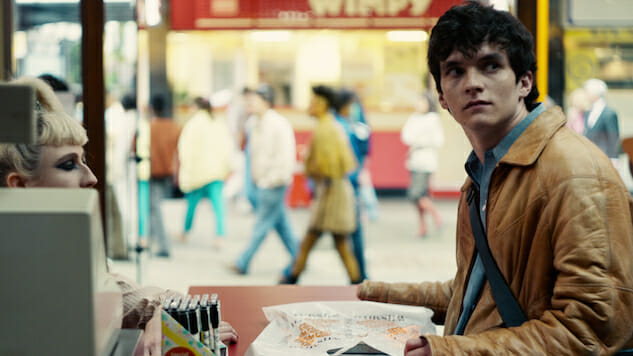

Photo: Netflix TV Features Black Mirror

A critic sits down at a keyboard, beginning a review. In his hand is a book on criticism, written by Roger Ebert and full of—he hopes—tips and principles he’ll be able to apply to the subject matter at hand. If it’s good enough, perhaps he can attract a publisher for a compilation of his work. The only problem is, as soon as he writes his first words, he is consumed by self-doubt. His artistic contribution is constantly interrupted, torn down, and restarted because of his own self-critique.

While this self-defeating and facile scenario may sound like a depressingly accurate description of the writing process, it’s also what happens when you try to make something that’s entirely self-referential. It has no point beyond itself; it’s merely an exercise in “can I do this?” A critic failing to criticize because of self-criticism doesn’t have any meat on its bones: It’s a tongue-twister to describe, a surefire bore to depict on screen, and—despite my best efforts—still more interesting than the trite fluff of “Bandersnatch.” “Bandersnatch,” the first interactive entry into Charlie Brooker’s technophobic, twist-centric anthology series Black Mirror, loves its gimmick so much that it devotes its every atom to circularity and metatextuality, amounting to little more than breathy “aren’t we clever” cuteness.

That’s a shame, especially since the actors—who definitely had a weird, novel, and likely difficult time pulling it off—do fine work and the filmmaking is completely passable. The episode’s ostensible protagonist (aside from Netflix itself and you, the player/viewer), Stefan, is done justice by Fionn Whitehead… if only there were something there for him to do justice. Whitehead is definitely good at staring, head cocked and eyes incredulous, while we decide which of the two choices to select for his character. Stefan is trying to create a choose-your-own-adventure game in 1984, all while being the character in our choose-your-own-adventure game in 2018. Everything else in the world exists in service of this parallel gag, and its stoned, debate-team take on free will.

The concept of interactive fiction is already so familiar—in RPGs, visual novels, and movies like Stranger than Fiction and Ruby Sparks (not to mention actual books, which “Bandersnatch” references)—that making it meta without much else to care about removes the motive to pursue all those alternate realities. Is “Bandersnatch” particularly labyrinthine? Mind-bending? Not so much, for those outside the experience. Those inside? Well, Stefan realizes he’s being controlled by us; a kid (Will Poulter) drops acid and talks about Pac-Man. It’s a metaphor for society, man. And this episode? Its figurative meaning is almost beside the point because its literal narrative is so determined to jam in as much meta nonsense as possible that it becomes silly and disjointed.

You can kill a character and not think twice. Go crazy and fail to blink an eye. Step into the past, and wonder only if this is the “right” ending. As Stefan’s therapist points out during one scenario (your adventure may vary) explicitly about the concept of Netflix, if this is all for entertainment, why isn’t Stefan in a more entertaining scenario? Rather than producing more action, more adventure, or more out-there invention, though, “Bandersnatch” ultimately reduces itself to choose-your-own-adventure-ness: It’s a simulated fractal, the careful calibration of which is its only selling point. If there’s no reality to it, how could reality be an illusion? If there is or isn’t a system, is or isn’t trauma, is or isn’t madness, then whether or not we care is hugely important. And since every line of dialogue, every glance, and every detail is a wink—imagine an hour-and-a-half of Jim from The Office deadpanning into the camera—the form never makes space for the actual content to begin.

Returning “Metalhead; director David Slade bows to Brooker’s worst scripting impulses, creating an episode more interested in Easter eggs and its own complexity than telling a story. (So many ways to play! So many endings! So much to do and so little reason to do it!) Netflix’s other interactive offerings, Puss in Book: Trapped in an Epic Tale and a show based on Minecraft, are better realizations of the form. This high production value commercial for the streaming service’s newest offering simply plays off our morbid curiosity, then makes us complicit in its poor storytelling. The sadism of the TV audience is surely damnable, but making empty, vapid fiction interactive in order to own that audience is nothing but a self-congratulatory pat on the back for embracing a business model that would be considered dystopian in the universe of Black Mirror itself.

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch is now streaming on Netflix.

Jacob Oller is a writer and film critic whose writing has appeared in The Guardian, Playboy, Roger Ebert, Film School Rejects, Chicagoist, Vague Visages, and other publications. He lives in Chicago, plays Dungeons and Dragons, and struggles not to kill his two cats daily. You can follow him on Twitter here: @jacoboller.