Under Color of Authority: TV Takes on the 1992 L.A. Riots, 25 Years Later

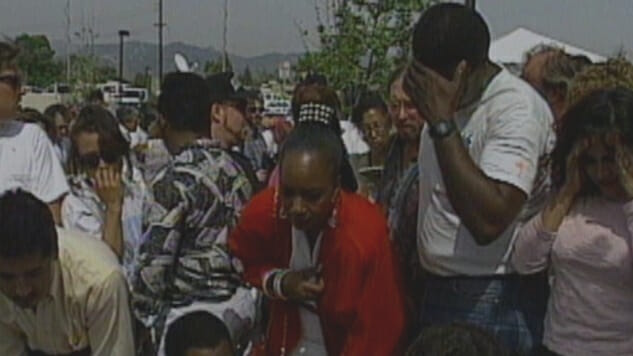

Header image courtesy of ABC TV Features L.A. Riots

What are you even supposed to say? A quarter century later, what are you supposed to say about the appalling Rodney King verdict and its sickening aftermath? That it was wrong? The word doesn’t begin to cover it. That it should have been foreseen? I’m pretty sure it was. That it was the fault of the jury, the defense team, the police chief; the officers who obeyed the order to stay out of south central Los Angeles while it burned to the ground? The rioters who beat and shot passersby and torched their own neighborhoods in a blind rage? The Korean shop owner who’d shot that black teenage girl in the back of the head and the mousy white judge who’d overturned the guilty verdict and given the murderer probation because “I know a criminal when I see one”? That it was the fault of the long, long history of tolerance for excessive force and racism in the LAPD? Of the stable blue collar jobs that had drained from the area, leaving a wake of poverty and despair and drug dealers and gang wars?

Short answer? Yeah. For starters. Slightly longer answer: It’s both simpler and more complicated than any of those things and much as “why?” is a question we always want to answer, it’s probably not the right question any more.

To commemorate the 25th anniversary of the riot or uprising or “incident” that torched Los Angeles in the wake of the 1992 Rodney King trial, National Geographic, A&E, Netflix, Showtime, ABC and the Smithsonian Channel have all produced films on the subject, and I recommend that you watch more than one, though it will be painful. Actually, do it because it will be painful. Seriously. Each of them has its own methodology for contending with the “why.” All of them together make it clear that what we need to be asking now is, “What will it take for human beings to wake the hell up and start actually learning from our own history?”

It was, arguably, the first “viral” video. The world saw it. Over. And over. And over. We saw it and were horrified and no matter how many times they played it we never stopped being horrified. A black man who had provoked a high-speed chase through the streets of Los Angeles was removed from his vehicle and beaten to within an inch of his life by four white cops, illuminated by the spotlight of a police helicopter. A man in the building across the street saw what was happening and documented the incident with his video camera. He tried to take the tape to the police. The police didn’t want it.

But the media sure did. In fact, the tape was seen so many times that the defense attorneys moved to re-venue the trial because public attention had made it impossible to get a fair hearing in Los Angeles. (Public attention would have made it equally impossible to get a “fair” trial in the Aleutian Islands.) Nonetheless, the motion was granted and the trial moved to a town in Ventura County where approximately one in three adult residents was in law enforcement. The policemen who savaged Rodney King were acquitted, to worldwide shock, of having used “excessive and potentially deadly force under color of authority.” What happened next remains the most destructive civil disturbance in U.S. history (and one of the most destructive, period). The 1992 Los Angeles riots lasted five days, claimed 55 lives, injured more than 4,000, and caused $1 billion in damage to the city. Depending on your age, you might or might not have a clear memory of it: That footage was sickeningly familiar to me. And if you’re a little older you probably know that this was not the first time a riot broke out in Los Angeles over rampant racism and police brutality. It was just the most lethal.

So far.

Showtime’s Burn Motherfucker, Burn!, directed by Sacha Jenkins, probably goes the deepest into the decades preceding the 1992 riots, in particular Watts in the 1960s but also the Pachuco riots of the 1940s. It spends less time on the actual Rodney King case and the disastrous aftermath of the verdict, but it will ground you very firmly in the reality that what happened in 1992 was anything but unpredictable.

On the other end of the spectrum is Spike Lee’s Netflix production, Rodney King, which stars Roger Guenveur Smith in a one-man dramatization of the life and death of “the first reality TV star.” Epistolary, explosive and heartbreaking, Guenveur’s performance will make you want to look away-but you won’t be able to.

National Geographic’s LA 92 does a masterful job of presenting fact and footage without filters or commentary—it feels almost like a slideshow, and that does have a certain power, but I found myself wishing they’d dig deeper. Like the Showtime documentary, it hearkens back to news coverage of the Pachuco riots (also known as the “Zoot Suit” riots) of June 1943 and the commentator’s horrified questioning about whether something like this might happen in Los Angeles in the future. But it raised a number of questions that it didn’t seem to answer. I guess some questions don’t have answers. Maybe that’s the point.

John Ridley’s Let It Fall: Los Angeles, 1982-1992, on ABC, is a gut-wrenching and kaleidoscopic oral history, combining the commentary of both police and civilians; it’s multi-generational, multi-ethnic, and provides perhaps the richest sense of context for the riots; by the end of this one you’ll understand that in most ways, the riots were basically inevitable and not particularly about Rodney King. Los Angeles was a tinderbox long before the night he was battered by those cops. Their acquittal happened to light the match, but anything might have.

Smithsonian Channel’s The Lost Tapes: LA Riots collages footage from the six days of the uprising, presenting it as if it were happening in real time. It’s (appropriately) chaotic and uninterpreted; among other things, it gives viewers an important sense that this could be happening now. Because here’s the thing: It is. The insanity in South Central in 1992 remains unparalleled in the scope of its destructiveness, but that’s not because police decided excessive force and the systematic targeting of people of color wasn’t a good plan. It’s just become so commonplace it hardly gets airtime any more.

Rodney King wasn’t an innocent bystander. He was an addict with a record and he was driving drunk. In no way does that mean those men did not meet (and massively exceed) the criteria for use of excessive force under color of authority, a legal term that roughly means “using your position of power to justify an illegal act.” The evidence was unambiguous and overwhelming. In the immediate aftermath of the incident, even L.A. Chief of Police Daryl Gates said, on camera, that he was horrified to see his officers engaging in excessive and probably criminal use of force against an obviously subdued suspect. I say “even” Daryl Gates because the night the riots started, he was not at his desk. He was at an anti-police-reform fundraiser in wealthy Brentwood, making on-camera quips about how he was glad the chopper was there to illuminate the scene of the beating—otherwise “the lighting would have been terrible.” And because there’s a chilling piece of footage from a press conference in which Gates makes a thinly veiled threat in response to criticism of his department’s long record of brutality. He basically says, If you think the LAPD is so terrible, let’s see how you feel when the shit hits the fan and we’re not there. (I am paraphrasing.) A reporter asks Gates to clarify whether he has just threatened to punish critics of the department by refusing to respond to calls for law enforcement assistance. Gates has a tantrum, slapping the desk with his hand and yelling that it was irresponsible people like that reporter who were the whole problem. (Again, I’m paraphrasing.) But when the rioting started, Daryl Gates ordered the LAPD to turn their backs while innocent people were injured or killed and neighborhoods were reduced to ash. Los Angeles saved the asses of four corrupt cops. The cost to the city was 55 lives, more than 4,000 people in hospitals, and a billion dollars. That is some remarkable math.

Seen from the viewpoint of, say, a police helicopter, Los Angeles looks like a vast mosaic. Which is essentially what it is. When you look at anything from that kind of remove, something becomes very obvious: Multiple things can be, and are, true at the same time. One truth does not always, or even most of the time, invalidate another. Things are happening everywhere all the time. No one is all good or all bad. There are honest and dishonest ways of looking at situations and there are ignorant and informed ways of looking at situations and no one can see what they cannot see. Right? So we do the best we can with the means at our disposal. Right?

Well, theoretically. Apparently, the best the LAPD could do was insist those cops didn’t abuse their power the night they kicked Rodney King’s skull to pieces. It’s chilling to imagine how things might have been different if even one of them had just said, “I fucked up. I freaked out, went into a rage, and beat the shit out of a guy who was clearly already subdued-plus. In that moment I did not see Rodney King as a human being. Guilty.”

There is a moment in Burn Motherfucker, Burn! in which Jenkins, interviewing current police chief Charlie Beck, asks, “If you were in my body, would you be scared of the police?” Beck pauses, recounts that as an undercover officer he was pulled over hundreds of times by cops who appeared to be targeting him for his dilapidated car and long hair and that “there is always tension.” (Jenkins is extremely gracious about the glaring apples-to-oranges comparison.) Then Beck says something that is firmly in the “All the shittier for technically being the truth” column. He says the solution is “Empathy. On both sides of the glass.”

These six documentaries show hours and hours of human beings who have lost any and all sense of this thing we call empathy—you can’t watch it and not get that what the whole explosion in 1992 boils down to people just fucking refusing to acknowledge other people as human. Stacey Coon didn’t see Rodney King as a person. Soon Ja Du didn’t see LaTanya Harlins as a person. Damian Williams and the other three men who dragged Reginald Denny from his truck and bashed his skull in with a cinder block did not see Denny as a person. There are assuredly a lot of racist assholes in law enforcement, and there are probably at least as many who are just scared shitless and traumatized because when you confront armed, violent people for a living it’s actually pretty scary. I’d bet the number of untreated PTSD cases in an average large-city police department would boggle the mind. But the minute you stop seeing the person in front of you as a human being with an equally valid right to exist, both of you are screwed. Empathy is, indeed, the only hope for fixing it. And empathy is, technically, available to all humans at all times. There’s just this one little hitch.

If you’re trained to expect inhumanity—at the hands of an abusive parent, a racist institution, a violent spouse, a war—your field of vision will narrow until all you see is the need to be on guard against whatever abuse of power is coming at you next. That is part of the human package. When there is tension between two groups of people and there is a vast, vast power differential between them, and a long history of blatant and flagrant and hideous injustice, you’re asking way too much of the person with no power to lead with empathy toward someone whose baton has just broken three of his ribs because his registration was expired. So, Charlie Beck: I’m not inclined to disagree with you on the empathy front. But it’s awkward, man—the LAPD remains the most murderous police force in the country. So I hope you get why the “empathy” has to be much, much more relentless than the brutality has been. And why it has to start with you.

Because what happened in 1992 was not random, or inexplicable, or unique, or something that won’t happen again. If you’re at all unconvinced on that front, I have six documentaries to recommend. Pay special attention to the one you’re in and listen to what you’re saying.

Burn Motherfucker, Burn!, The Lost Tapes: LA Riots and L.A. Burning: The Riots 25 Years Later are now available on Showtime Anytime, Smithsonian Channel and A&E, respectively. Rodney King premieres Friday, April 28 on Netflix. Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992 premieres Friday, April 28 at 9 p.m. on ABC. LA 92 premieres Sunday, April 30 at 9 p.m. on National Geographic Channel.

Amy Glynn is a poet, essayist and fiction writer who really likes that you can multi-task by reviewing television and glasses of Cabernet simultaneously. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.